Rethinking the Repertoire #23 – Henry Cowell’s Piano Concerto

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twenty-third in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

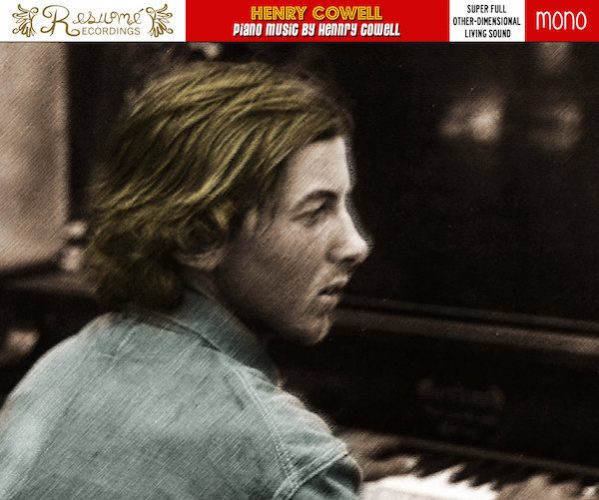

Composer Henry Cowell — an outsider’s outsider.

If you know of Henry Cowell, it’s probably as a figure on the fringes of the American maverick tradition. He was that – but more, too.

Born in Menlo Park, California in 1897, Cowell had no formal musical training until he was a teenager. His parents, who described themselves as “philosophical anarchists,” allowed him a wide-ranging education: Cowell taught himself the piano, immersed himself in Asian cultures he encountered throughout nearby San Francisco, and started composing. At seventeen, he met Charles Seeger (husband of Ruth Crawford, father of Pete), who became something of a mentor to him.

After World War 1, Cowell’s career took off. He gave his debut recital in New York, toured Europe, and became the first American musician to visit the Soviet Union. His travels allowed him to meet the who’s-who of early-20th-century contemporary music, including Schoenberg (he played for his composition class in Berlin), Bartók, Ravel, Roussel, and others. Back in the United States, Cowell was a champion and early biographer of Charles Ives and founding editor of the journal, New Music.

He taught widely, at U.C. Berkeley, Stanford, Mills College, Peabody Conservatory, and other schools. Among his students were John Cage, Lou Harrison, and Burt Bacharach.

Arrest and imprisonment on a morals charge in the late-‘30s (he was pardoned in 1942) resulted in a conservative shift in his musical output over the last quarter-century of his life, but, until his death in 1965, Cowell remained among the front ranks of the progressive element in American music.

And what a creative body of music he left. Though Cowell didn’t invent the “tone cluster” (as he’s often credited – that distinction belongs to one Vladimir Rebokov), he did create the term and used the technique (of playing adjacent notes on the keyboard with fists or forearms) so widely that it became something of a calling card: Bartók actually asked Cowell’s permission to use the device in his own music!

There’s more to Cowell than just clusters, though. His piano compositions pushed the technical and sonic limits of the instrument. The Banshee, Cowell’s landmark score from 1925 is perhaps the most extraordinary demonstration of his ingenuity, a work in which every sound is created by the pianist drawing his or her hands across the strings under the piano’s lid.

Other pieces, like the Six Casual Developments, draw on jazz. The Sinfonietta channels the pungent expressivity of the Second Viennese School while the Mosaic Quartet anticipates the aleatoric procedures of a later generation (or two).

Moreover, Cowell’s ideas had a profound influence on his students and contemporaries. John Cage’s invention of the “prepared piano” – a process of inserting screws, tubes, erasers, sheets of paper, and other objects in between the piano’s strings – was directly inspired by Cowell’s experimental writings for the instrument. And his theories about rhythm held considerable sway both with composers (like Conlon Nancarrow) and later inventors (whose mid-century rhythm synthesizers would draw on concepts articulated by Cowell in the 1920s and ‘30s).

In all, then, Cowell’s was an important, if now often forgotten, voice in 20th-century music. His contemporaries acknowledged that fact. No less than composer/critic Virgil Thomson paid him a handsome tribute in the 1950s, writing:

Henry Cowell’s music covers a wider range in both expression and technique than that of any other living composer. His experiments begun three decades ago in rhythm, in harmony, and in instrumental sonorities were considered then by many to be wild. Today they are the Bible of the young and still, to the conservatives, “advanced.”…No other composer of our time has produced a body of works so radical and so normal, so penetrating and so comprehensive. Add to this massive production his long and influential career as a pedagogue, and Henry Cowell’s achievement becomes impressive indeed. There is no other quite like it. To be both fecund and right is given to few.

But where is his music now and why?

Since his death at 68, Cowell’s star has, except for the reputation of certain of his most striking pieces, faded a bit. Part of this owes to the variable nature of his output. Some of it of a high order, for sure. But Cowell was a prolific composer (he wrote twenty-one symphonies, for example) and not all of his music is at the same expressive or technical level.

What’s more, he’s been eclipsed, at least in terms of influence, by certain of his students. Cage, in particular, looms over the next couple of generations of contemporary composers (even as his music remains less familiar than his writings). In the meantime, Cowell recedes.

That’s unfortunate because Cowell was always much more than just a musical philosopher and innovator. While a German critic, writing in the politically-charged year of 1932, sarcastically commented that “the musical inmates of a madhouse seem to have held a rendezvous” in response to Cowell’s employment of fist- and forearm-produced tone clusters during a Berlin recital, it’s Thomson who had the full measure of the man. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine another composer of any nationality of the 20th century who produced a body of music at once “so radical and so normal.”

One of the best introductions to Cowell’s considerable corpus is not through the near two-dozen symphonies (though they have their moments) but, rather, via Cowell’s magnificent, idiosyncratic Piano Concerto. Premiered in Havana in 1930 it surely is among the most rarely-performed concerti in the canon: among the top seven U.S. orchestras (the traditional Big Five, plus the Los Angeles Philharmonic and San Francisco Symphony), it’s only been played by the San Franciscans – and then, just since 2000. But it’s a dazzling piece all the same: brash, raucous, and heartfelt.

There are three movements. The first is called “Polyharmony.” It opens with a discordant blast from the orchestra and then the soloist enters. Piano and orchestra proceed to alternate dense, dissonant ideas that run the gamut from lyrical to spiky. And neither overstays their welcome: within four minutes, the movement’s done.

At the heart of the piece comes the middle movement, “Tone Cluster.” Like the first, it’s packed with a peculiar mix of songful melodies and crunchy harmonies. But it never settles down into anything predictable. Canorous tunes crop up here and there, only to be interrupted by driving, rhythmic refrains and, starting about a third of the way through, episodes of thudding piano clusters. Even in the more aggressive sections, though, there’s a dulcet quality to Cowell’s writing: it never loses sight of the melodic line (or, at least, the idea of one), and the movement holds together with remarkable coherence as a result.

For the finale, “Counter Rhythm,” Cowell turns over another leaf. Here, various layers of rhythmic activity bounce off of and are superimposed upon one another. Snatches of the “Dies irae” chant emerge throughout and the music passes through something of a vale of shadows over its middle section. But all ends gloriously, with furious, Liszt-ian runs culminating in a thunderous cadence in C major: the revolutionary and the canonic, sitting gleefully side-by-side.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.