Visual Arts Interview: New Publics — Art for a Modern India, 1960s-’90s

What was the influence of Western modernist imperatives on an art-making culture far removed from Europe and the US?

New Publics: Art For A Modern India, 1960s-90s. Curated by Yael R. Rice. At the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College, Amherst, MA, through July 1.

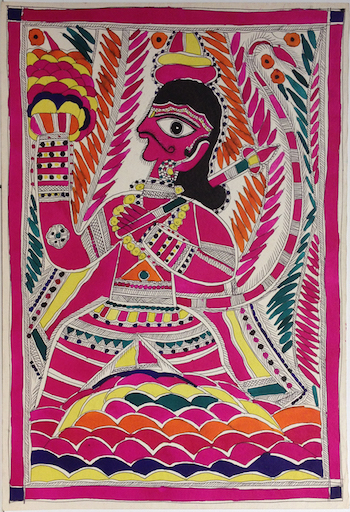

Bachni Devi, “Vishnu on Cosmic Ocean.” Photo: courtesy of Mead Art Museum at Amherst College.

By Timothy Francis Barry

What’s your relationship to other cultures? Mine tends toward intense curiosity, undercut with what I hope is not a whiff of xenophobia: I fear the unknown. I don’t like not knowing. So when faced with images that reflect traditions and concerns alien to my own, I find myself a bit uncertain.

Such was the case when looking at the retinally vibrant exhibition of modernist Indian painting now on at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College. Dizzyingly colorful, the show brings together narratives that puzzle and tantalize, works which raise questions that resist easy answers.

In 1959 Modernism in painting had come up to cruising speed. At that time the great abstractionist and teacher Hans Hofmann said: “As a teacher, I approach my students purely with the human desire to to free them from all scholarly inhibitions.” These inhibitions led to what was later termed “the anxiety of influence,” or, put simply, it’s a tall order to make truly original art.

The 1960s brought a packet of pluralist modes — minimalism, color-field and the dregs of abstract expressionism gave way to neo-expressionism in the ’70s, and a hodge-podge of approaches like ‘combines,’ wherein you could afix a goat’s head, or some antlers, to a canvas and generate a masterpiece.

This head-spinning gamut of styles and tendencies dominated the production of Western art. The question raised by this exhibition was this: what was the influence of Western modernist imperatives on an art-making culture far removed from Europe and the US?

I posed this question to the curator of the show, Yael R. Rice, and her answers are revealing.

Arts Fuse: What was the extent of exposure of these artists to contemporary Western art?

Yael Rice: Jamini Roy, Sunil Madhav Sen, MF Hussain, and Sunil Das — to varying degrees — were familiar with contemporary art from Europe/N. America, as well as in East Asia (especially Japan). As a member of the Progressive Artists’ Group (PAG) in Bombay (Mumbai), MF Hussain also had contact with a group of influential European Jewish refugees who had settled in Bombay. Roy, who is considered to be one of India’s ‘forefathers’ of modern art, exhibited in London as early as the 1940s. All of these artists were exceedingly cosmopolitan, well-traveled, and well-read.

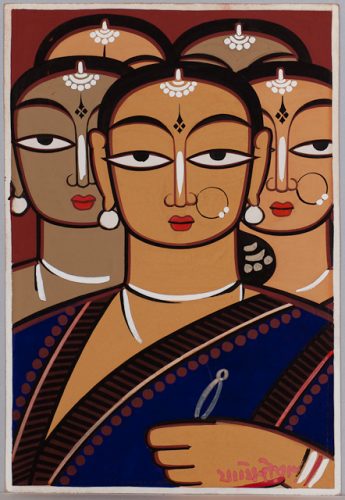

Jamini Roy, “Untitled (Five Women).” Photo: courtesy of Mead Art Museum at Amherst College.

The patua (scroll painter) and Mithila artists, on the other hand, would have had much less—if any—exposure to contemporary art from the second half of the 20th c. These artists live(d) mainly in villages. The patua artists are more mobile (itinerant, actually), but are extremely poor.

AF: Is this selection representative of a tendency in Indian art of that time, or are these breakaway artists, outliers?

Rice: Yes, I would say that the works by Roy, Sen, Hussain, and Das are representative of one strand of Indian post-war art — that is, one that was concerned in particular with investigating local “Indic” practices, forms, and technologies — though each did so towards different ends. Hussain and Das, more so than Roy, experimented more with abstraction, in parallel with what some artists in Europe/N. America and elsewhere were doing. Roy, more than the others, cultivated a practice and self-image as a “rural” painter (when he was in fact educated at the Govt College in Calcutta and extremely cosmopolitan). Hussain’s Through the Eyes of a Painter film, in contrast, could be said to be an attempt to bridge urban and village ‘making’ — a response to contemporary political debates about citizenship and nationhood in the newly independent India.

The vernacular artists tell a different story, of course. They belong to communities that produce collective styles and modes of art production.

Shanti Devi, “Hanuman.” Photo: courtesy of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College.

So, this concise and yet eye-opening exhibition shows artists in varying modes of creation, in some cases employing centuries old images and archetypes to generate art with a contemporary spin. For example, Shanti Devi’s psychedelic Hanuman (c.1990-1991), features a devotee of Lord Rama and one of the central characters in the various versions of the epic Ramayana. The watercolor by Devi, born 1963, catches the eye via a riot of colors and patterns.

In a similar vein, artist Shyam Devi depicts a story from Hindu mythology in her Krishna Dancing On The Serpent Kaliya (c.1990-1991), yet she treats the past in a wholly different manner. The watercolor makes use of a carefully detailed micro-pattern in a way that recalls American vernacular rural art, sometimes called Outsider Art. The latter is created by untrained, marginalized makers: the mentally ill, prisoners, and religious zealots. Is it a coincidence that separate cultures, removed by thousands of miles and many oceans, can produce art that suggests such strong connections? Even if it is a matter of chance, it is still thought-provoking.

Sunil Das is represented by an untitled work of mixed media and collage on paper dating from 1967. The piece recalls Western art by Jean Dubuffet and even Jean-Michel Basquiat, both of whom factored ‘primitive’ iconography into their artworks. Das (1939-2015) even seems to allude to Picasso via his slightly off-kilter rendering of a human figure.

All of these resemblances and resonances, Rice points out, “illustrates the intertwined relationship of cosmopolitan and vernacular artistic traditions.” Which, to this observer, mostly begs questions regarding sources and borrowings,and influences. Yet how much does it really matter if the art is compelling, as it is here.

Timothy Francis Barry has written for the Boston Globe, New Musical Express, Brooklyn Rail, Aesthetica Magazine, artcritical and artsfuse.org. His first column was under the editorship of Byron Coley at Take-It Magazine. He operates Tim’s Used Books in Northampton, Mass., and Provincetown, Mass., which book critic David L. Ulin, called his “favorite bookstore in America.” (Los Angeles Times, 8/29/13)