Book Review: “Pandora’s Box” — An Illuminating Study of Epic Destruction

Pandora’s Box never tosses the reader into a roiling overload of facts and figures, but looks at the horrors of WWI from many different, illuminating angles.

Pandora’s Box: A History of the First World War by Jörn Leonhard. Translated by Patrick Camiller. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1087 pages, $39.95.

By Thomas Filbin

The First World War was called the “war to end all wars” but, of course, it wasn’t. A little more than twenty years after its end its combatants were at it again, this time at an accelerated level of killing. The Treaty of Versailles is usually the prime culprit, given the harsh demands for reparations it handed a Germany now broken and broke. But other factors were to blame as well. Colonialism and imperialism led the major powers to believe both before and after WWI that they could and should control the destiny of millions of people who never saw their faces, much less elected them. Reconstructing the world in 1919 reflected a battle between realpolitik and idealism. British Prime Minister Lloyd George, who had to negotiate with France’s Clemenceau and Woodrow Wilson, remarked, “I feel as if I am in between Napoleon and Jesus Christ.” It could be argued that the great nations of the world, having suffered the catastrophe of 1914-1918, learned nothing from it.

This is last of the centenary years for the “Great War” (its other name), and there have been an accumulation of commemorative books, observances, and speeches, with more to come by November 11, the 100th anniversary of the Armistice. Jörn Leonhard, a professor of history at Freiburg University, has contributed a lengthy but very readable history of the war; thankfully, it is far more than a list of battles, but a thoughtful consideration of the epic destructive event in all its varied ramifications.

At the outset, Leonhard shows how this conflict was different from early warfare. It gave us the notion of total war, meaning one in which neither civilians nor property were excluded from demolition in any way. Earlier wars, such as the Franco-Prussian war of 1870-71, were mindful of military objectives. Once Germany had defeated the French army at Sedan and captured Emperor Napoleon III, they were done and left the French to fight among themselves in a civil war between the Communards of Paris and the national government of Thiers. The Germans wanted Alsace and Lorraine annexed, not destroyed.

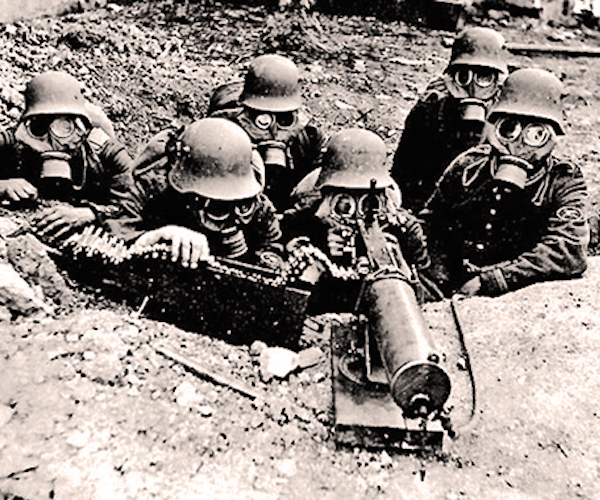

In the Great War all means to achieve victory were considered desirable, especially as the years dragged on and the illusion of “home by Christmas in 2014” evaporated. The eventual use of poison gas is a prime example: at first thought uncivilized, even in violation of international war, there was initially skepticism about its benefits. As Leonhard writes, “…officers well knew from experience that the enemy would develop similar weapons and that, in this war, traditional ideals of fair and generally accepted rules of combat were no longer enforceable.” Evidence is provided by a quotation from General von Einem, commander of the German Third Army: “But I am furious about the use of gas, which from the beginning struck me as repulsive. …this unchivalrous instrument, otherwise used only by rogues and criminals (was)…thought (to win the war) in almost no time… (but) now our enemies have it, too.”

A scene from World War I.

One of the military aspects of the war that receives considerable coverage in Pandora’s Box is trench warfare. Wars in previous centuries made use of large aggregations of soldiers facing off on a field of battle, such as Waterloo. Leonhard explores how WWI was often about paralysis (one of his chapters is titled “Stasis and Movement”). He chronicles how armies dug in for months and years, advancing and retreating by yards and meters in an extensive network of trenches. He observes that this sort of warfare set up a new kind of psychological test for soldiers; hours of monotony in cramped quarters were followed by sudden artillery assaults. Bombs rained down, tearing up the earth. Trenches made soldiers safer, but encouraged a protracted war. A striking aerial photograph in Pandora’s Box doesn’t picture warriors ready to attack — it is a dankly lined and pock marked landscape devoid of vegetation.

It could be argued that the great nations of the world, having suffered the catastrophe of 1914-1918, learned nothing from it.Click To TweetTruces, such as the famous Christmas Eve truce of 1914 in which soldiers ventured outside of the lines to exchange cigarettes and food, were not uncommon. Humanitarian pauses occurred, to retrieve casualties and bury the dead. In theory, these were condemned by senior officers, but they usually had the good sense to look the other way. Leonhard observes that “…large scale troop fraternization was quite exceptional. However, special conditions affecting everyone…might lead to temporary truces, as in mid-December 1915 when heavy rain in the area of Neuville—Saint-Vaast flooded the trenches so badly that both sides gathered in no-man’s-land and in some cases began to sing the ‘Internationale.’”

Social history is not omitted in this account of the conflict. The attempts of liberal political parties to advocate peace are covered, although in some countries, such as Russia, dissent was quickly suppressed. In some nations, peace movements were condemned as defeatist and cowardly. English philosopher Bertrand Russell went to jail because of his opposition to the war; Union leader Eugene Debs was imprisoned for his anti-draft activities.

Women replaced men in war industries. Leonhard and other historians state that the two World Wars, for all their horror, proved to be vehicles of advancement for women, although not by patriarchal intent. Once women proved they could do a job, the door had been opened, at least a crack.

Author Jörn Leonhard.

One subject covered with impressive insight in Pandora’s Box is whether the war could have been ended sooner; by the winter of 1917 the carnage and horror had gone on for more than three years. All the combatants had suffered terrible casualties and Pope Benedict offered a peace plan, disturbed that Catholics and other Christians on both sides were carrying on the slaughter with sustained enthusiasm. But his offer was viewed by the Allies with suspicion because they felt the Vatican was tilted toward the Central Powers, particularly the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Also, at that point, the war seemed to be moving toward the advantage of Germany, especially after the end of its hostilities with Russia. Leonhard posits that Germany underestimated the importance of America’s entry into the war, which took place in April, 1917. It was downhill from there; American reinforcements of weary Allied troops tipped the balance. The fall 1918 offensives hastened the inevitable conclusion. Two million American soldiers in France, half in front line positions, procured victory for the Allies.

There are more books on the First World War than anyone (even enthusiasts) could read, but Leonhard’s is an honorable addition, a large and weighty volume, literally and metaphorically, that is well worth the time dipping into. Well researched and detailed, Pandora’s Box never tosses the reader into a roiling overload of facts and figures, but looks at the horrors of WWI from many different, illuminating angles.

Thomas Filbin has reviewed books for newspapers, magazines, and academic journals.

Tagged: Jörn Leonhard, Pandora's Box, Pandora’s Box: A History of the First World War, Tom Filbin