Jazz CD Review: “Seraphic Light” [Live At Tufts University]

The players are striking out into the unknown: you may find the journey inspiring and you may sometimes find yourself lost in the woods.

By Steve Provizer

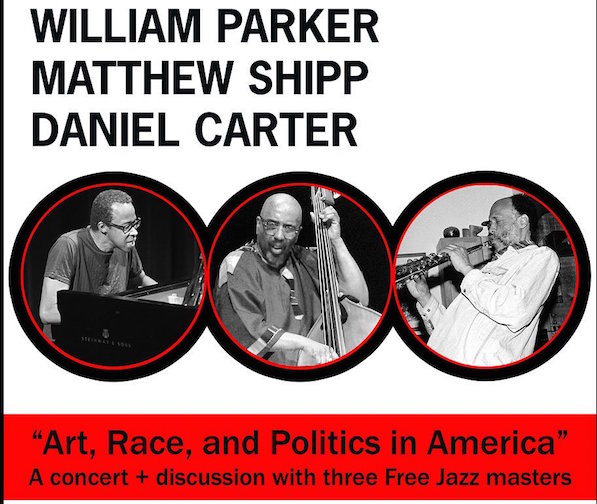

Seraphic Light (AUM Fidelity) was recorded live at a concert at Tufts University as part of an event held in April, 2017 entitled Art, Race and Politics. The evening included a screening of the 1959 documentary The Cry of Jazz, written and directed by Edward O. Bland as well as a panel discussion featuring musicians Daniel Carter, William Parker, and Matthew Shipp, who then combined as a trio to give this live performance. Carter plays a variety of reed instruments and trumpet; Shipp is on piano and Parker on bass. They are among the most celebrated musicians operating today in the area of free improvisational jazz. I use the terms free and jazz for the sake of shorthand and advisedly, knowing that the musicians themselves raise issues with how the music they play is characterized.

The recording is broken up into three parts that are 21, 21, and 16 minutes long. I can’t explain why they divided parts one and two in the middle of a passage of music and why the audience’s applause at the end of section two is at the beginning of section three. The music shifts rapidly within each section and there is no overriding musical conception that compels separating the sections this way.

One hears immediately that each of these players is skillful enough to perform whatever they want. Shipp and Parker are virtuosi (the latter’s bowing technique is otherworldly) and Carter plays well.These musicians can hear “around the corner” as the expression goes. But chops are less important when it comes to evaluating this music than by determining how well the musicians fuse together for the sake of creating a unified musical vision. The players strike out into the unknown: you may find the journey inspiring and you may sometimes find yourself lost in the woods.

There are no pre-arranged structural or other musical elements to anchor aesthetic judgment. The music unspools in real time, as each musician decides to take off in an individual direction, or to respond to what someone else is playing. In this context, you can’t suggest that someone played the “wrong” chords, or a that a solo didn’t “swing.” A different set of expectations and critical listening skills are called for.

When I review a CD I often go through each song, providing descriptions (non-musical analogies or metaphors) of the expressiveness of the music. That isn’t a particularly relevant approach in the case of Seraphic Light. What might be useful is to tell you some of the overriding tendencies and elements that recur more often than others. Shipp uses the whole keyboard and is fond of triplets, using them at different speeds in various contexts. As noted, he shifts motifs often and makes use of a wide palette of rhythmic techniques and variations in attack. His playing may remind you at different points of other pianists, but he is a distinctive player. Carter tends to play mostly tonal, “inside” lines. He varies his timbre, moving from a lighter to a more Coltrane-like sound. He blows occasional flurries of notes, but more often his lines are melodic and controlled. Parker, as noted, is a master of the bow and is capable of contributing a wide range of sounds, which often have a human vocal quality. And he can “walk” with the best of them.

Matthew Shipp in action. Photo: Daniel Sheehan.

One key musical element one can listen for in this music, or one way to listen, is determining whether or not the musicians have created a tonality that did not previously exist. Is a “greater than the sum of the parts” quality generated in a particular performance? Think of it this way: the musical background of each of the players informs his musical decisions. One may have had classical training, another might have come up in the blues, a third may have been trained as a bopper. The tonality — as I use the word here — is the result these backgrounds mixing together in a free situation. The players must decide quickly (instinctively, really) as they shape the ideas that spontaneously arise or take the lead in forging new ideas.

Overall, this creative mixing is effectively done. A new tonality is arrived at from a coherent blending of new and/or recognizable elements derived from older forms of jazz: blues, new classical, and a tradition of free music playing. Shipp and Parker are constantly attuned to each other, whether the playing called for balls out or quiet. Shipp’s performance changed almost constantly, presenting new harmonic, melodic, or rhythmic motifs Parker responded to — nay, committed to — quickly and in full voice. To my ears, Carter was sometimes not able to blend his energy and aesthetic with the others; he either could not penetrate a given musical moment or his choices made him somewhat of an outsider. At other times, the different powers of the trio’s musicians merged — or the differences in their approaches paid off.

I myself play music of this kind and recognize that if you’re new to it, appreciation can be difficult. Listening requires a combination of concentration and letting go. You have to pay careful attention, but you also have to be in a receptive state of mind, able to ride with the sudden changes in the music. The payoff comes if you arrive at this state: the aesthetic rewards are very different than those found in the more common AABA jazz byways.

Occasionally, I felt that I was listening to three minds at odds. But most of the time I entered the zone and was inspired by the music. At its best, the music of Seraphic Light sounds as if it emerges from one living, breathing organism.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.

Tagged: Daniel Carter, free jazz, Matthew Shipp, Steve Provizer, Tufts University