Book Review: Susan Sontag’s Collected Stories — From the Back Burner

Susan Sontag wrote short stories as a hobby; she saved more of her enormous intellectual energy for her novels and essays.

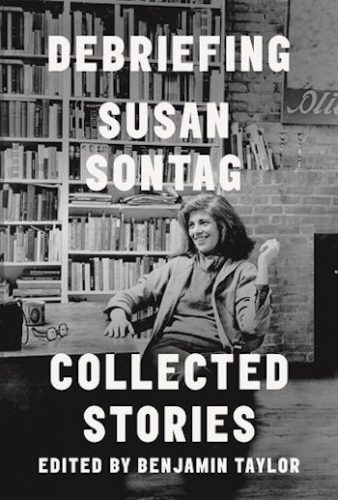

Debriefing: Collected Stories by Susan Sontag. Edited by Benjamin Taylor. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 336 pages, $27.

By Matt Hanson

Susan Sontag once defined a polymath as “someone who is interested in everything — and in nothing else.” In her work as much as her life, Sontag definitely lived up to her own standard. The essays “Notes on Camp” and “Regarding the Pain of Others” are more relevant than ever. Her political activism was fierce, courageous and profoundly felt, if at times leading her to make regrettable statements. Sontag’s legendary erudition and passion for the freedom that fiction allows infused everything she wrote but it generated an interesting irony: while Sontag wrote an enormous amount about literature, she didn’t produce nearly as much of it herself.

The new edition of her short stories collects everything that appeared in 1977’s I, Etcetera with a few new additions, including her brilliant lament “The Way We Live Now.” The introduction suggests that Sontag wrote short stories as a hobby; she saved more of her enormous intellectual energy for her novels and essays. The point is also made that Sontag’s omnivorous intellectual curiosity got in the way of writing fiction at the rarified level in which she could discuss it.

“Pilgrimage” starts off the collection with a lightly fictionalized account of an amusingly prodigious adolescent. She and her best friend sit in a car surrounded by smooching couples “debating the merits of the Busch and Budapest Quartets” and swooning over “how many more years of life for Stravinsky would justify our dying now, on the spot?” Her account of meeting the exiled Thomas Mann at his splendid California home for tea is sweetly awkward. She gazes up at the august German author and tries her best not to say anything stupid. Most teenagers of the early sixties would’ve pined to meet the likes of Bobby Darin; it’s charming to see how Stravinsky and the author of The Magic Mountain were her ideas of a rock star.

At their worst, her stories are intellectual finger exercises. “Project for A Trip to China” discusses, at length and in detail, the narrator’s long held desire to travel to China. That is all: the postmodern conceit quickly loses its novelty. The last sentence is a real doozy: “Perhaps I will write the book about my trip to China before I go.” Baudrillard be damned; it’s probably better to actually go somewhere first before writing it up. In “Unguided Tour” she comes up with a brittle contrast to what the story about the hypothetical trip to China could have been. Two unnamed characters sit in an unnamed location and talk obliquely to each other about their vague surroundings and their ever-so-slightly changing attitudes towards it. Instead of being evocative, the effect is dreary and reeks of overthink.

The stories come to life when Susan Sontag sheds her ponderousness and romps through some fun satirical conceits.Click To Tweet“American Spirits” reflects a different aspect of Sontag’s hyper-erudition. The yarn features bickering characters (annoyingly named Miss Flatface and Mr. Obscenity) and adds some weird cameos from the “spirits” of random cultural figures who hover, like furies, over their conversation: “now she felt the tug of sex loyalty. The spirits of Edith Wharton and Ethel Rosenberg whispered hoarsely in her ears, beckoning and forbidding.” I don’t know what those two have in common, if anything, and I gave up trying to figure out how or why they “beckon” or “forbid.” Mr. Obscenity has William James and Fatty Arbuckle beckoning and forbidding on each of his shoulders, which is an even weirder pairing. Grafting cultural references into your text might sound good in theory but doesn’t always work out on the page.

The stories come to life when Sontag sheds her weakness for ponderousness and romps through some fun satirical conceits.“Dummy” is about a dummy that blends in to the human world without anyone around him much noticing. If anything, the self-involved humans seem to appreciate the complacency and agreeableness of their new companion. “Baby” is narrated by a mother telling her psychiatrist about her unruly infant, whose brash and outrageous behaviors make him more “adult” than his increasingly insecure parents. The baby smokes, drinks, has a box of condoms under the bed, and gobbles junk food while murmuring random facts about Napoleon. The witty twist is that the mother’s greatest worry turns out to be whether her parenting skills are properly progressive enough.

The volume’s undeniable masterpiece is its final story, “The Way We Live Now,” which was published in The New Yorker in the mid-’80s and is set during the beginning of the AIDS crisis. Sontag’s experiments, beautifully, with voice and authorial indirection: the stricken main character’s suffering is delicately alluded to through the reactions of his friends, lovers, and acquaintances via a palimpsest of overheard voices. We don’t just understand the tragedy of a single person’s needless death; we understand the meaning of that loss from listening to the widening circle of those affected by it. Their uneasiness reminds us how, at one time, AIDS was a strange, mysterious, and almost forbidding illness. The result is a powerful, graceful, and deeply politically engaged narrative. Finally, Sontag is writing fiction that is worthy of her sophisticated imagination.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.