Classical CD Reviews: Barenboim plays Sciarrino, Berio, Tartini, and Paganini and Alsop’s Complete Bernstein

Marin Alsop’s eight-disc set tribute to Leonard Bernstein stands as an impeccably curated and revealing portrait of one of American music’s true giants.

Violinist Michael Barenboim — he is an exceptional young musician with a famous name who stands on his own two feet. Photo: CAMI Music.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Here’s an apple that didn’t fall far from the tree. Violinist Michael Barenboim’s father is the noted musician-intellectual Daniel Barenboim; his mother is the accomplished pianist Elena Bashkirova. One shouldn’t be surprised, then, that his musical chops are so impressive. Or that, programmatically and interpretively, he proves so thoughtful a musician.

His newest album, which pairs virtuosic solo violin repertoire by Salvatore Sciarrino, Luciano Berio, Giuseppe Tartini, and Nicolo Paganini, is thrilling and captivating for all of those reasons, but most of all because it cements the arrival of an exceptional young musician with a famous name who stands on his own two feet.

This is clear from the disc’s first selection, Sciarrino’s Six Caprices for solo violin. They’re studies of extremes: of the physical limits of the violin, of the musical abilities of the soloist, of the ear’s capacity to process disparate sounds as musical gestures. Only about twenty minutes long, they’re not for the faint of heart.

Barenboim plays them with staggering control and a strong sense of how to focus their wispy themes into compelling musical paragraphs. He does this largely by using color and articulation to unify the music’s structure. So, the second Caprice’s flickering textures dance around like so many delicate tongues of flame. The third skitters about like a car chase in a Bond flick. Slashing bow strokes in the fourth evoke a woozy, phantasmagoric scene. And the finale, with its bursts of glissandos and rapid-fire, scale-like figures seems to take the shape of Paganini before continuously morphing into something else.

Ditto for Berio’s wild, coruscating Sequenza VIII.

In case you were wondering, nothing gets easier with the album’s older pieces. There’s a knotty lyricism to Barenboim’s performance of the solo violin version of Tartini’s “Devil’s Trill” Sonata, and he capably navigates its demands, but, in his hands, it’s clearly cut from the same granitic cloth as the more recent scores.

So are the six excerpts from Paganini’s Caprices that close the accentus disc and balance out the ones by Sciarrino. Perlman played them a bit more suavely and beautifully, but Barenboim’s rawer approach links them squarely to a still-evolving virtuoso tradition. That is, ultimately, an irresistible way to look at this music, old and new.

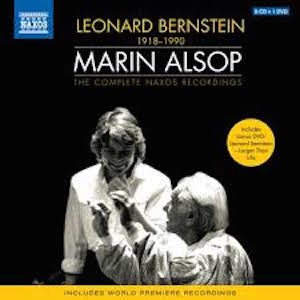

It’s appropriate that two of Leonard Bernstein’s most notable conducting students are also a pair of his finest posthumous advocates: Michael Tilson Thomas and Marin Alsop. While Tilson Thomas’s Bernstein discography is relatively small, Alsop’s is anything but. For Bernstein’s centenary this year, Naxos has compiled all her recordings of her mentor’s music, plus a few other pieces, in a handsome, eight-disc set. It’s not the definitive Bernstein or complete but, at its best, it stands as an impeccably curated and revealing portrait of one of American music’s true giants.

The highlights are several. There are excellent performances of Bernstein’s first two symphonies. Alsop’s 2008 account of Mass continues to stand tall. Bernstein’s concertante works are featured in recordings that rival his own, particularly Fancy Free, the Serenade, and Chichester Psalms. Lesser pieces are given due justice, particularly Slava and the withdrawn CBS Music. And, though no full musicals are present, Alsop’s recordings of a handful of excerpts – the “Dance Episodes” from On the Town, the “Mambo” from West Side Story, Overture to Wonderful Town, and a Suite from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue – are winningly done, especially the latter.

On the debit side, Claire Bloom makes a rather stiff narrator in the original version of the Kaddish Symphony. Surely the piece’s shortcomings aren’t all her fault – Bernstein’s text gets pretty tendentious – but her performance is a pale shadow of Felecia Montealegre’s manic, frenzied reading from 1964. Kelley Nassief’s accounts of Kaddish’s soprano solos are warm and clean; the Maryland State Boychoir and Washington Chorus sing strongly; and the Baltimore Symphony plays with plenty of panache and color, but the whole performance doesn’t quite add up to the sum of its parts.

Also, there’s unfortunately little here from Bernstein’s last decade – no Halil, nothing from A Quiet Place, the Concerto for Orchestra, or Arias and Barcarolles – and the 1970s are only haphazardly represented (Dybbuk and Songfest are conspicuously absent). The set’s biggest dud, in fact, is the collection’s most recent score, a stiff rendering of the 1981 Divertimento.

The nearest we get to Bernstein in the ‘80s are A Bernstein Birthday Bouquet and Garth Edwin Sunderland’s orchestrations of eleven piano Anniversaries. The former consists of eight short-ish arrangements of “Happy Birthday” and “New York, New York” written by various Bernstein contemporaries in honor of his seventieth birthday in 1988 and here recorded for the first time. They’re often quite clever (Luciano Berio’s works in snatches of Beethoven and Wagner along with the start of “The Star-Spangled Banner; William Schuman’s fits in a nod to Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man, and so on) and very well played by the São Paulo Symphony Orchestra.

The latter set actually spans most of Bernstein’s career, but six of the movements Sunderland selected hail from the last volume of Anniversaries, published in 1989. Some of his arrangements – “For Craig Urquhart,” “For my daughter, Nina,” and “For Leo Smit,” particularly – work well. But most of them don’t transfer successfully to orchestra, sounding cumbersome and heavy-handed, which probably owes more to Bernstein’s spare, intimate keyboard writing than anything else.

Even so, there’s much in this collection that impresses. And, in an anniversary year that’s already seen much repackaging, this one offers a few gems you won’t find elsewhere. Best of all, it showcases a conductor who’s pulled off one of the trickiest feats with Bernstein’s music: making it, by and large, totally her own and convincingly so. For a composer whose music has been indelibly stamped by his own recordings and performances of it, that’s perhaps the greatest tribute Alsop could pay her mentor.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: accentus, Leonard Bernstein, Marin-Alsop, Michael Barenboim