Book Review: “Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts” — Pages of Glory

De Hamel’s history is a detective story, a love story, and a revelation of the nourishment to be found in celebrated libraries and collections.

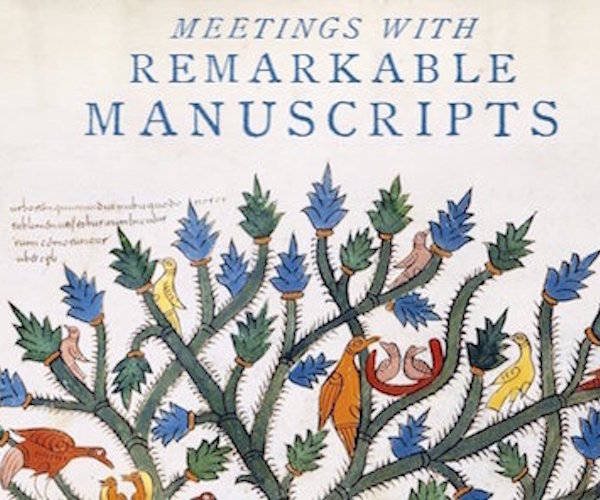

Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts: Twelve Journeys into the Medieval World, by Christopher de Hamel. Penguin Press, 632 pp. $45.00.

By Thomas Filbin

One might suspect that a work about medieval manuscripts would be a dull tome, worth its soporific weight in Ambien. But Christopher de Hamel’s brilliant book turns out to be a yarn well spun, a ripping tale filled with enchantment and intrigue as it details how twelve manuscripts came to be, what they signify, and how they have survived.

Penguin Press is to be lauded at the outset for having enough faith in this book and books in general to publish it so beautifully, with hundreds of color plates interspersed in the text. It is a physically handsome object whose charm transports the reader into a time long past. You can practically hear ancient monks chanting the Divine Office while dipping their pens in colored ink, illustrating texts both sacred and profane.

Given wars, revolutions, fires, vandalism, and the predations of thieves over the centuries, the survival of these treasures is astonishing. Those curators and collectors who have had custody of the manuscripts plainly saw their calling as not only noble, but semi-divine. Of course, the arrival of the digital age presents a new threat to their existence: will future generations treasure these texts as much, or consider them to be merely quaint, cobwebbed detritus from olden times?

Christopher de Hamel has both scholarly and commercial experience: doctorates from both Oxford and Cambridge and a long career as an expert for Sotheby’s. He knows how to make the trials and tribulations of the past exciting by cultivating the reader’s curiosity — the texts are at the center of a series of adventures and investigations. “If there is a single theme which I would try to convey if we were actually undertaking these journeys together, it is what pleasure you can have looking at manuscripts. I want to know everything about them. I want to know who made them and when and why and where…how they were copied… and decorated…what materials were used…what they cost…how they have survived against all odds…and under what circumstances they reached the custody of their current owners.”

Note this scholar’s humility: American experts tend to boast; British historians embrace understatement and self-effacing humor. “I took the Latin option at school, not because I had any particular aptitude for it (I hadn’t), but because I was generally worse at everything else,” de Hamel explains.

Among his selections is the Carmina Burana, a thirteenth century manuscript compiling songs and poems of life and love, twenty of which were put to music by Carl Orff. De Hamel notes that “most are in Latin, but the volume has scraps in various European languages and important pieces in Middle High German, which are among the oldest surviving vernacular songs. The manuscript of the Carmina Burana is by far the finest and most extensive surviving anthology of medieval lyrical verse and song, and it is one of the national treasures of Germany.” He takes his time exploring the Carmina, his discussion cuts against the stereotype that medieval people were absorbed in their religiosity. In truth, they were as much concerned with love, lust, and laughter as any other generation.

The Book of Kells in Dublin’s Trinity College Library is among the most visited tourist attraction in Ireland — over a half million people a year view it — and its history, at least in de Hamel’s telling, does not disappoint. Dating from about 800, the manuscript contains the four gospels of Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John: it is as much a work of art as biblical literature, filled with dazzling illustrations and ornamentation.

Other manuscripts de Hamel examines include The Morgan Beatus, a tenth century treasure (owned by New York’s Morgan Library) which features interpretations of the Apocalypse by a Spanish monk, Beatus. Examining the volume, the author notes that “although Beatus is a documented writer, his name does not actually occur in any of the manuscripts. However, his authorship was attested by the late Middle Ages and it has been universally accepted.” The composition of the book was begun around 776, and de Hamel argues that the obsession with the Apocalypse coincided with cultural intimations of the decline of the old Roman-Hispanic civilization. The arrival of the Berbers from North Africa and the Umayyad Caliphate in Cordoba may have suggested the “end times” to the Spaniards.

Historian Christopher de Hamel. Photo: United Agents.

Other texts presented here include The Copenhagen Psalter, the Hours of Jeanne de Navarre, The Gospels of Saint Augustine, and the Hengwrt Chaucer of about 1400, the latter held by the National Library of Wales and identified as copied by one Adam Pinkhurst, a scribe who had been admonished by Chaucer himself to be more careful in his work. The Guardian newspaper in 2004 ran the headline “Chaucer’s sloppy copyist unmasked after 600 years.” Detective work in dusty old archives can be a jolly bit of fun at times, de Hamel reminds us. He is a writer who conveys the joy of intellectual sleuthing, never becoming lost in technical matters or minutiae.

Spellbinding medieval manuscripts can be found in Boston; many of our local libraries and universities own eye-filling specimens. A recent sighting: the splendid tripartite exhibition More Than Words; Illuminated Manuscripts in Boston Collections, which was jointly mounted in 2017 by Harvard University’s Houghton Library, the McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College, and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. The exhibit presented an impressively rich collection of well-preserved works, examples of texts from times when piety, wonder, and learning were an essential part of literary creation.

Part of what makes de Hamel’s study so riveting is that he knows illuminated manuscripts don’t have to be treated as sacred texts. The author notes that, when he visits rare book libraries, he watches scholars poring over the precious volumes as if they were monks reading their breviaries. De Hamel takes a far less intimidated (and intimidating) approach, and that is all to the good. At a time when too many eyes are turned to imagining the future (on screens), when even the “now” is passé, the immutable value of these venerable volumes needs to be articulated for a non-academic readership. Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts fits the bill: it’s a detective story, a love story, and a revelation of the nourishment to be found in celebrated libraries and collections.

Thomas Filbin is a freelance book critic whose work has appeared in newspapers, literary reviews, and academic journals. He lives in Westwood, MA.

Tagged: Christopher de Hamel, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts