Arts Remembrance: “Purified Modernist” William Gass — A Wizard of the Word

William Gass’s primal loyalty was to the words composing his texts.

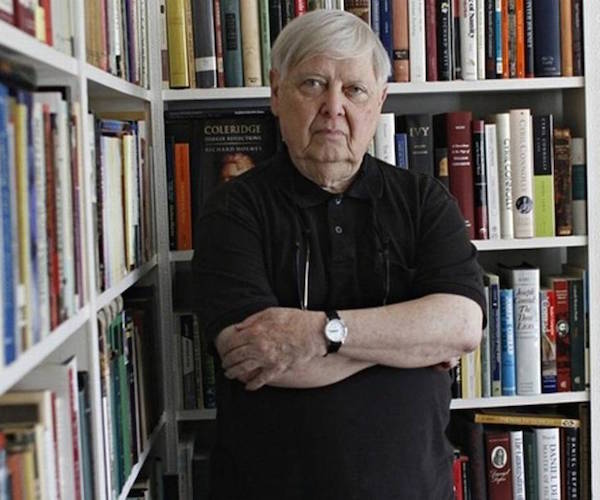

The late William H. Gass — his world was words, a way of being.

By Vincent Czyz

The world for William Gass was the word. Or maybe it was the other way around. Gass, who died on Dec. 6, 2017, at the age of 93, bequeathed to us a literary legacy that will likely be decades in the measuring.

Unlike Aristotle, Gass was not a fan of plot as an organizing principle. In his essay “Finding a Form,” he argued that “there’s bird drop, horse plop, and novel plot. Story is what can be taken out of the fiction and made into a movie. […] Story is what you do to clean up life and make God into a good burgher who manages the world like a business.” He coined the term metafiction to describe writing by the likes of Jorge Luis Borges and John Barth, whose fictions were often about fiction. He held character to be a higher consideration than plot (once again flouting the Poetics), but more important than either in Gass’s work is language itself.

Sentences, he maintained, are “containers of consciousness”; they are thoughts rather than representations of thought. The sentence, Gass asserted, if it is to outlive its maker, must have a soul, not “merely be a sign of the existence somewhere of one.” It must find “in its drive and rhythm … the verbal equivalent of instinct.” He treated the “style and characteristic structure of the sentences that filled the novel … as microcosmic models for the organization of the whole.” This is not to say his stories and novels are plotless; rather, the stories he tells are not the prime movers of his fictions. His loyalty was to the words composing his text.

William Howard Gass was born in Fargo in 1924, but his family left the hinterland of North Dakota shortly thereafter and resettled in the steel town of Warren, Ohio. Gass’s essay “The Doomed in their Sinking” (collected in his volume The World Within the Word and anthologized in The Best American Essays of the Century) alludes to an unhappy childhood presided over by an embittered father, a bigot who badgered and bullied the younger Gass’s mother. Passive by nature and beset by the man she’d married, she drank so excessively that the blood vessels in her throat eventually burst.

After a three-and-half-year stint in the Navy during World War II, Gass went on to earn a PhD in philosophy (1954) at Cornell University, where he studied for a short time under Ludwig Wittgenstein. He landed at position at Ohio’s College of Wooster before moving on to Purdue University, where he labored in the fabled obscurity of the artist who is late to the party success has planned for him. Manuscript after manuscript was rejected. In his preface to his collection In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, Gass recounts the story behind a story that took him some eight years to see into print: “you can imagine how many editorial rejections (it seemed liked hundreds; I can still hear flat slap of the ms. on the front step, the sting of shame in my cheeks; my humiliation, doubts, confusion; I heard the laughter of thousands).” Worse, in a scenario out of a movie script, a colleague at Purdue stole a novel manuscript out of Gass’s desk drawer. True to a favorite Hollywood trope, it was his only copy. The perpetrator was eventually found out, but Gass was forced to reconstruct the novel from notes.

Omensetter’s Luck turned out to be Gass’s good fortune. The New Republic’s Richard Gilman touted the novel as “the most important work of fiction by an American in this literary generation.” Susan Sontag described the book as “extraordinary, stunning, beautiful.” While Gass had placed a few short stories in small literary magazines and even had three chosen for the annual Best American Short Stories anthology (1959, 1961, 1962), his name was not widely known, even in literary circles. Omensetter’s changed his luck.

I first encountered Gass’s work in college, where his story “In the Heart of the Heart of the Country” appeared on a class syllabus. While I found it an oddly irresistible read, I didn’t quite know what to make of it. I read Omensetter’s Luck in my late twenties, and the effect was striking—like lightning illuminating a nighttime landscape: For an instant of startling clarity, I saw what I had been traveling through.

The novel describes the fallout in a small town after worldviews collide—one embodied by Brackett Omensetter, a man of “natural goodness,” and the other by Jethro Furber, a clergyman who, though driven half-mad by repressed sexual longings and visions of violence, preaches with eloquence. His sermon, the high point of the book, alludes to Empedocles, reeks of Gnosticism (“We are here—yes—yet we do not belong. This, my friends, is the source of all religious feeling.”), is laced with Pascal’s lament for the trivial uses to which we put the mundane miracle called consciousness. Existentially rattling, it is as beautifully worded as a poem by Walt Whitman.

But so is the rest of the book. In the margin of an age-tanned page of my battered paperback, I wrote a note to the author: “Your language is preternaturally natural, as if you threw all those words up in the air and they drifted down arranged in these sentences. You covered your tracks—you’re not there. Even through fresh snow fell all around you. All the reader sees is the perfection of an unbroken surface.”

Here, Gass describes rural Ohio at the turn of the 20th century (the novel’s setting):

Trees, hills, river … yet life was monotonously flat, straight … plankish … with a dreadful sameness everywhere like dust … a climate without any real extremes, deprived of virtue even in its mean … and the moments ran on mindlessly like driven cattle, and young men struggled in the net of their friends, relatives, and other connections for a while like dripping fish before wearing out their wills and settling down to live with the rest of the gently poor, their pets, and their obsequious diseases … where bitterness grew up on everything like ivy.

His magnum opus, however, is The Tunnel, reputedly 29 years in the making (though he published a number of books in that time as well). The narrative is a daunting 652 pages rarely honeycombed by dialogue. The plot, such as it is, is simple: William Kohler, a history professor—and an odious, Nazi sympathizer—has composed his own magnum opus. But unable to compose an introduction that will finish his history of the Third Reich, he becomes paralyzed. Rather than face the typewriter, he begins digging a tunnel in his basement, as though, through his burrow, he can escape his life, his past, and the repulsive soul that inhabits his body. When I was at about the 180-page mark, I wrote to a friend to say that I doubted The Tunnel was a novel; it seemed to me a very long, very dense poem. Put another way, I wasn’t reading to see what happened next; I was running mental fingertips over the texture of the prose, watching for another lyrical observation, listening to the lines as they faded into echoes in my inner ear. There is no page, probably no paragraph, that lacks a lustrous sentence.

Tall, thin, slightly cadaverous, Uncle Balt’s voice issued from his body as from a length of pipe. […] I saw him rarely, so he retained a foreign flavor for me, an exotic far-offness that his mustache—two droopy loops of thin black rope—did nothing to diminish. He had an immense stride, and a posture like his gaze: straight, unbending, blunt. Work had pastured his face the way weather wears a field. Past burning, beyond tanning, not even any longer leathered, it seemed the sorrowful smoothing out of some angrily wadded paper, his bones like the shadows of bones behind his skin …

A bit of questionable grammar aside, Gass’s verbal portrait is worth framing. Another of the numerous passages of arresting prose from which to choose is Kohler’s recollection of a grim autumn:

I felt not just lonely but abandoned, abandoned by myself, of course, as though I’d put myself in someone else’s storage, but abandoned also by my papers and my pen, my favorite books, my language. The room I’d let, like so many in [the work of] Rilke, was filled with unbreathable foreign air and dresser mirrors into which my face fell like a blemish in the slivered backing, fell and remained fallen … clouding the glass like a hot palm, lying there like a leaf-shaped shadow, a ghost worn out as a glove.

The novel is somewhat disjointed, yes, collage-like at times, but so elegantly wrought the conventions of traditional narrative can be let go without much regret. And, with the advent of Trump, with its revelation (for some) that millions of Americans not only adore him but will not rescind their adulation literally no matter what he does (61% of his base according to a recent Monmouth University Poll), The Tunnel, with its fascist narrator and Party of Disappointed People—a collection of Kohler clones—begins to look prescient.

But Gass cautioned against using fiction to purvey “truth,” a Teflon-coated concept if ever there were. “Truth, I am convinced, has antipathy for art,” he writes in his essay “Philosophy and the Form of Fiction.” “It is best when a writer has a deep and abiding indifference to it.” In The Tunnel he observes that “Experience is broad and muddy, like the Ganges, with the filthy and the holy intermixed in every wash …” Similarly, he points out in this essay “Finding a Form” that “History is often written as a story to seem to have a purpose, to be on its way somewhere” and suggests “that life is no more than an endlessly muddled middle.” He therefore “rejected a realism that wasn’t real,” that neither reflected the world nor his experience of it. Hence his decision to demote plot in favor of exploring lexical enigmas, digressing in ways that drove story purists to tear their garments, and writing sentences that were ends in themselves, not mere grammatical contrivances conveying the illusion of action.

For someone universally declared a wizard of the word, he earned few awards for his fiction (four Pushcart Prizes) although his books of criticism pulled in three National Book Critics Circle prizes. He never won a Pulitzer or the National Book Award. No PEN/Faulkner. Part of the problem, I don’t doubt, is that sentences have become disposable in fiction; there’s no shortage of badly written books winning prestigious awards. Perhaps the most eloquent defense of prose style—his or anyone else’s—is “The Soul Inside the Sentence,” an essay he ends by suggesting that “if we cannot have an everlong life, perhaps we can create a soul, within some substance elsewhere and other than ourselves, which it would be a crime on the world’s part to let die.”

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Tagged: In the Heart of the Heart of the Country, Omensetter's Luck, postmodern fiction, The Tunnel

I’m still reluctant to read Gass, but you certainly made a great case for him, and I put his quote about the Ganges into my little diary.

I highly recommend Gass — one of my favorite American writers. I would suggest starting with his essays, then moving onto his fiction. A good way to begin your journey — The William H. Gass Reader coming out next June from Knopf. The generous selection (900 pages!) of fiction and non-fiction was made by the author himself.