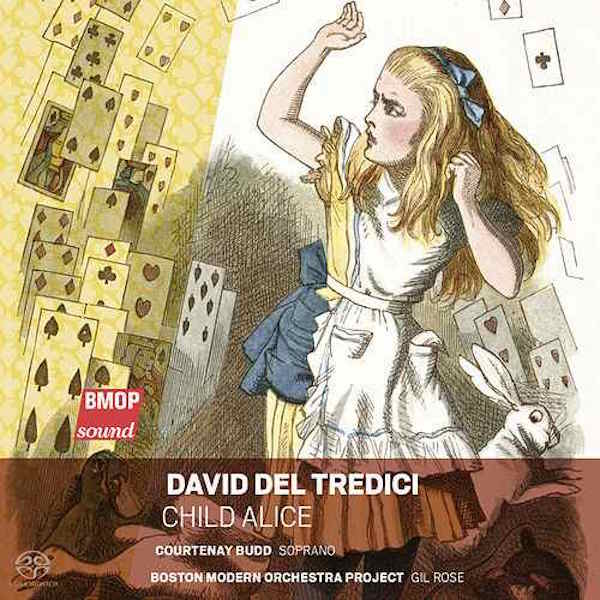

Classical CD Reviews: David Del Tredici’s “Child Alice” and Scott Wollschleger’s “Soft Aberration”

Child Alice is an important addition to the recorded catalogue of major American symphonic music; Wollschleger’s album places him as one of the Millennial generation’s most striking voices.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Few works of literature compare, for sheer invention, spirit, and zaniness, with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. So it’s appropriate that David Del Tredici’s Child Alice, the sixth of his ten (to date) settings of Carroll texts, sounds like pretty much nothing else in the canon. Well, maybe that’s not entirely true. In Child Alice, Del Tredici emulates the styles of Mahler and Elgar pretty strongly, and there’s a dash or two of Ives to be found – as well as hints of a good half-dozen or so other canonical voices.

But it speaks to the strength of Del Tredici’s musical argument and the conviction of his writing that none of these inferences detract from the music’s expressive riches (nor is the score just a collage of old sounds: it’s plenty spiky, acerbic, and dissonant, too). Quite the opposite: these gestures infuse Child Alice with a certain charm that, thirty years after its first full performance, is rich and nostalgic, yes, but plenty forceful and, above all, staggeringly brilliant. Indeed, at this point one can focus Child Alice’s poignant depths, its moments of giddy ecstasy, its reservoirs of sadness and terror, more than its stylistic quirks, which are no where near as controversial or shocking as they were three decades back.

If Child Alice’s pages are marked by a kind of Lisztian excess (at least in its scoring), they share a directness of spirit and expression that’s reminiscent of Beethoven (or, maybe better, Wagner) at his most dramatically daring. Written between 1977 and 1981 and setting poems that preface Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, Del Tredici’s score is an often-unsung and, before now, unheard late-20th-century masterpiece. The Boston Modern Orchestra Project’s (BMOP) new recording of the piece (taped at Jordan Hall last spring) rectifies that last problem, and it does so with abandon.

One of the reasons Child Alice has remained obscure owes to its vocal demands. It’s a piece that requires a soprano of Wagnerian stamina (she sings for about an hour-and-a-half) as well as voice that can navigate the stratospheric acrobatics of bel canto. In Courtenay Budd, BMOP and Del Tredici have an ideal soloist, one whose singing evinces purity and innocence but also strength of character and a certain mischievousness that suits this music well. Her diction is largely excellent, even in the highest-tessitura passages, and, expressively, she brings a winning understanding to Del Tredici’s treacherous vocal writing.

If the soprano part is wickedly difficult (and it is), Del Tredici’s orchestral writing is just slightly less so. BMOP’s performance here, though, makes easy work of the two purely orchestral movements (the march in the middle of “In Memory of a Summer Day” and Part II’s “Happy Voices”) and provides suitably atmospheric playing when accompanying Budd. There are a couple of tentative transitional spots here and there but the big picture comes across with pristine clarity and Gil Rose’s conducting ably captures the music’s sense of sweep and space.

In all, this Child Alice is an important addition to the recorded catalogue of major American symphonic music. It’s another demonstration of BMOP at its musical and missional best and marks a worthy way to celebrate Del Tredici during his 80th-birthday year. More than that, it’s a fine recording of a truly great piece of music that needs to be heard. Bravo, all around.

Composer Scott Wollschleger’s new album, Soft Aberration, is, on its surface, about as fresh and singular a new-music album as I’ve heard this year: on the one hand, Wollschleger draws on a spate of extended techniques and gestures that all sound thoroughly of the present. At the same time, there’s something elemental and profound at work, too, in this collection of five chamber pieces, and that intangible quality lends these pieces (and this disc) its expressive weight.

In the opening track, Brontal Symmetry, a piano trio written for the ensemble Longleash, thudding, mechanistic rhythmic patterns alternate with violent episodes and moments of pure stasis. Most of the piece’s gestures and textures – the string writing is frequently sul ponticello – are menacing, though Longleash ably draws out the music’s moments of nervous humor and peace, too.

The album’s title track, on the other hand, taps a very different vein. Meditative and spare, Soft Aberration, a viola-piano duet, evokes the sound worlds of Toru Takemitsu and Morton Feldman more than anything else: fragments of melodies appear and hover before dissolving into the ether.

The three parts of Bring Something Incomprehensible Into This World, a striking duet for voice and solo trumpet, frame the remaining pieces on the disc. A study of timbral contrasts that employs various extended trumpet techniques, Bring Something alludes (perhaps inadvertently) to a number of reference points, from Berio’s Sequenzas to Dizzy Gillespie’s bebop. But it’s a remarkably engaging and original-sounding piece, all the same, one that leaves an abiding impression.

Inserted between the parts of Bring Something come a pair of string scores. The first, America, is a rather manic essay for solo cello that investigates some of that instrument’s extended capabilities, as well as gestures (repetition, silence) heard in earlier works on the album. After America comes White Wall, a string quartet (played by the Mivos Quartet) that utilizes white noise techniques to craft a harmonic framework of breathtaking fragility.

All of the performances are given by the players for whom the respective pieces were composed and may well be considered definitive. There’s much to admire here, technically, from John Popham’s flickering intensity in America to the subtle shades of light and shadow Mivos teases out of White Wall to the sumptuous warmth pianist Karl Larson and violist Anne Lanzilotti bring to Soft Aberration.

But it’s those touchingly expressive moments that leave the biggest impact – in Brontal Symmetry and Bring Something, especially. Those elevate this album and cement Wollschleger’s place as one of the Millennial generation’s most striking voices.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "Soft Aberration", BMOP/sound, Child Alice, David del Tredici, New Focus Recordings