Book Review: “The Songs We Know Best” — The Youth of Poet John Ashbery

This book captures — beautifully — poet John Ashbery’s youth and dreams and struggles.

The Songs We Know Best, John Ashbery’s Early Life by Karin Roffman. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 316 pages, $30.

By Roberta Silman

When this book arrived in the mail I thought, John Ashbery may be one of our greatest American poets, but a book about his early years? There surely can’t be that much to say.

But I was wrong. This book, which begins with John’s birth in 1927 (he was 90 on July 28th) and takes us through his high school and college years until he left for France as a Fulbright Scholar in 1955, is a gem. It has a true voice, a feat rarely achieved by a biographer, and is as evocative as a fine novel in its sense of intimacy and tenderness towards not only John but his extended family and close friends. In fact, there were times when it reminded me of one of my favorite books of all time, What I am Doing, I Think, by Larry Woiwode. In short, I could not put it down, and when I did I felt that I had a much better sense of what American rural life was like in the ’30s and ’40s, how it felt to be discovering one’s sexuality both at Deerfield Academy and Harvard in the 40s, and the palpable sense of intellectual awakening in so many of the young who came to New York City in the early 50s.

Karin Roffman and John Ashbery met at Bard in 2005 when John, then in his late 70s, “visited a class” she was teaching in modernist painting and poetry. John and his long-time partner David Kermani and Karin became friends, she wisely realized there might be a book here, a diary was produced, and a project launched. Luckily there were friends and relatives still alive who could help, and the result is a story that is not only interesting in and of itself, but also enhanced by Roffman’s ability to sort out how that story fed the poetry that has made Ashbery so revered. Her references are inevitably relevant, and you begin to understand that all those plays and stories and poems that John composed as a child and teenager were important precursors to the mature poems. And when the story grows darker— John’s younger brother Richard died of leukemia when John was thirteen and Richard was ten — she conveys the grief that overcame the entire family and neighborhood with admirable dignity and restraint.

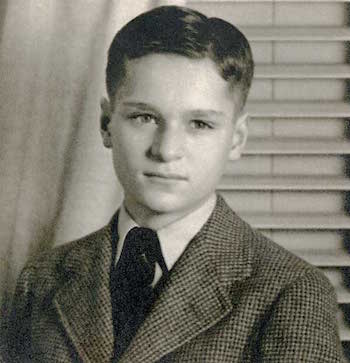

John Ashbery was born in the small upstate town of Sodus, New York, to Helen and Chet Ashbery; his mother was a homemaker and his father a fruit farmer who grew cherries in the summer, apples in the fall. His paternal grandmother Elizabeth lived with them, and although the household was nurturing and pleasant, John grew to prefer the more bookish home of his maternal grandparents, Helen and Addie Lawrence, in Pultneyville, where he spent his crucial Kindergarten year (the Sodus school did not offer Kindergarten) and, subsequently, his summers. He loved the attention to words in the Lawrence home and the neighborhood kids, some of whom became lifelong friends. All this caused tension with his proud father, which only grew as John veered into an entirely different direction from the family farm, of which Chet was so proud.

But his parents were loving and wanted him to enjoy life. Although not a particularly good student, John was clearly creative, a “quick wit,” and often at center stage when he and his friends produced plays in Pultneyville and at sleep away camp where he went for the first time in 1939 or in an art class his mother had arranged when the schools dropped art programs. An early poem called “The Battle” had even been admired by Mary Roberts Rinehart when it found its circuitous way to New York, but after that early success John concentrated more on drama than poetry and the winter of 1940 was a time of amazing physical (he grew very tall) and intellectual growth.

It was also a time of great stress for the family. John’s younger brother Richard, born in 1930, had been diagnosed with leukemia and died on July 5th. As was the custom of those days John had been shielded from the truth and shipped off to Pultneyville; when his grandparents told him his brother had died, he was totally bewildered. And utterly alone. Grieving was done very privately by Protestant families in those days and although close friends of the family took Chet and Helen and John on a wonderful trip to Blue Mountain Lake in the Adirondacks, it was a summer of confusion and shock, one that he would return to again and again as he matured, trying to make sense of the mysterious death of a younger brother with whom he had assumed he would grow up.

He had also become an only child. The following year he managed to become a Quiz Kid and traveled to Chicago for the famous show on which he seemed to move too slowly and answered only one question. But the adventure served him well, and he’d gotten a taste of traveling, which he would love all his life. Yet, as he looked backward that Christmas, he wrote “I would be happy with anticipation but should be happier if Richard were here. Christmas Eve is one of the happiest times but also the saddest.” As Roffman writes: “The uncommonness of his admission of feelings about Richard’s death, however, also reflected the magnitude of the loss, sadness that would dissipate over time but never fully disappear. Nearly sixty years later, Ashbery composed “The History of My Life,” a dark, fable-like poem that addresses his brother’s death directly, with unusual candor.”

Once upon a time there were two brothers,

Then there was only one: myself.

I grew up fast, before learning to drive,

even. There was I: a stinking adult.

I thought of developing interests

someone might take an interest in. No soap.

I became very weepy for what had seemed

like the pleasant early years. As I aged

increasingly, I also grew more charitable

with regard to my thoughts and ideas,

thinking them at least as good as the next man’s.

Then a great devouring cloud

came and loitered on the horizon, drinking

it up, for what seemed like months or years.

Here we see how grief persists, and hovers, for a lifetime. At the time, though, he had the resilience of youth, enormous curiosity about the world, and a need to learn all he could. He fell in love with Edgar Lee Masters and Amy Lowell and soaked up books like a sponge. Soon he was painting and writing Imagist poems and came to the attention of a wealthy neighbor who wrote a letter to the headmaster of Deerfield Academy, which her two boys had attended and, out of the blue, John was offered a place there for his third year of high school. If he did well, he could finish there. It was an offer he could not refuse.

As a great believer in public education which served my husband and me and our three children very well, I have always been somewhat skeptical of the value of private boarding schools. Reading about Deerfield Academy in the mid-1940s has only strengthened that skepticism. There John’s homosexuality became more overt and acceptable, which was fine, but the way the boys treated each other was sometimes appalling, almost unbelievable, as when one boy stole a poem of John’s and entered it in a contest as his own. However, John was up to the challenge and more than survived, doing well enough to earn a place at Harvard. Here he is, summing up the time at Deerfield:

Incidentally, I’ve beaten everybody that I’ve played tennis with, which has added a slight continental athletic torch to John Ashbery that queer duck who left Sodus a couple of years ago to go to some private school. Guess the high school wasn’t good enough for him. They say he’s goin’ to Harvard. Well, that is a good place for him, lots of queers there. He always was pretty bright—too bright for his own good, some say. (The foregoing sums up local opinion of me.)

John’s time at Harvard was really a wonderful new beginning both personally and professionally. He became more comfortable in his own skin. He also realized that he was a poet. There are some splendid bits about his friends, his literary accomplishments, and his important friendships with Kenneth Koch and Bubsy Zimmerman, who was in love with John and who became, later, the eminent Barbara Epstein, one of the founders of the New York Review of Books. These later chapters are full of the excitement of the life of the mind when you are young — those wild times when energy and imagination seem infinite.

John Ashbery in 1940.

Roffman writes about John at Harvard and later in New York so vividly and with such élan that you feel as if you are there with him, learning how to live by one’s wits. We feel his delight when he discovers Proust and Marianne Moore, we see at close hand not only Koch and Bubsy, but Jane Freilicher and Frank O’Hara, Larry Rivers, pianists Gold and Fizdale, Nell Blaine, even Auden, among many others. We trudge through boring jobs with him and we feel his grief after the suicide of his teacher F.O. Matthiessen and his resignation that chronic depression was going to be a fact of his life. We even squirm a little when we are told that John seemed to wake up with a new man every day, and I, for one, felt some relief that this wild ride in New York was not going to become his way of life when the Fulbright Foundation reversed itself and awarded him a fellowship and he finds himself on his way to France. What Roffman makes clear is that all through the craziness and exhilaration of that time John Ashbery was honing a talent that would grow — confidently and surely — until he became one of our most accomplished American poets.

I am also delighted that John and his longtime partner David Kermani are here to celebrate John’s big birthday and to see the publication of this book which not only captures — beautifully — John Ashbery’s youth and dreams and struggles, but also builds to a real, and, for me, unexpected high note: a work that chronicles a unique, often frantic time in New York, a work that will be valued by anyone interested in American intellectual history of the 20th century.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: American poetry, biography, Farrar, John Ashbery, John Ashbery’s Early Life, Karin Roffman, Straus and Giroux