CD Reviews: “Op. 2” and Faust/Melnikov’s Franck & Chausson

Violinist Sebastian Bohren’s sophomore album is uneven; violinist Isabelle Faust and pianist Alexander Melnikov have produced a wonder.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

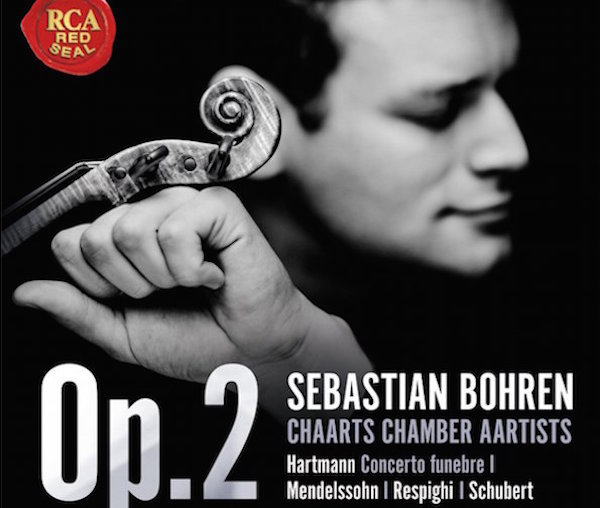

Violinist Sebastian Bohren’s sophomore album, Op. 2, suggests a young soloist with broader-than-usual tastes. What else to make of the pairing of music by Mendelssohn, Hartmann, Respighi, and Schubert? In the event, the disc is rather uneven, though, in at least one case, that owes as much to the quality of the piece as to the performance.

That work is Mendelssohn’s D-minor Violin Concerto. No masterpiece, it’s interesting largely because Mendelssohn wrote it when he was thirteen. And, for juvenilia, it’s not bad. Imitative, yes, but it puts the fiddle through its paces and there’s a certain variety present in its technical demands. The string orchestra writing has a couple of nice touches (low string trills and triplets at the end of the slow movement stand out), but is otherwise routine. Bohren and the Switzerland-based Chaarts Chamber Aartists play it all well and sweetly, but it’s hard to get past the music’s indifferent quality.

Karl Amadeus Hartmann’s Concerto funebre, on the other hand, is rather unforgettable – both on account of its origins and its materials. Written in the aftermath of the Nazi invasion of Poland in 1939, it’s a form of protest music that draws on a Hussite chorale and a song from the 1905 Russian Revolution, plus references to Baroque and Romantic gestures, all of which are filtered through Hartmann’s Modernistic harmonic language.

The Concerto is a stirring, heartfelt work and, in this performance, Bohren is a sometimes-very-soulful protagonist. The lyrical climaxes in the second movement come across fervently. He attacks the solo writing in the third with gusto.

But the whole performance lacks the epic intensity that Alina Ibragimova or Isabelle Faust bring to this score. The orchestral playing, too, is clinical: dynamics, for one, could be more consistently exaggerated (fortes and fortississimos sound virtually identical). Like the earlier Mendelssohn, everything’s a bit too clean and impersonal for the reading to really take off.

Where things start to work very well is in Ottorino Respighi’s Antiche danze ed arie, Suite no. 3. Here, Chaarts delivers a hearty, shapely performance of these smartly-crafted arrangements. The “Italiana” dances with grace and energy, while the “Arie di corte” glows. The “Siciliana” packs welcome contrasts of light and shade. And the closing “Passacaglia” emanates the sort of heat from which the earlier works on the album would have benefited.

Bohren leaves his best impression in Schubert’s D-major Rondo for Violin and Strings (D. 438), a piece that suits the elegant style of his playing better than anything else on this disc. Here, whether navigating the rhapsodic introduction or nimbly bounding through the music’s jaunty main section, he’s perfectly at home. What’s more, his playing sounds like this is where it can best shine, full of warmth, energy, and, when called for, pathos. Chaarts, too, seems to revel in the Schubertian spirit, accompanying with color and panache.

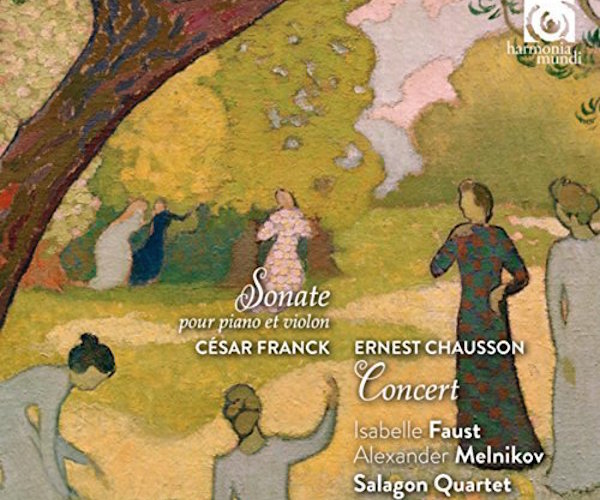

Who (or what) ever possessed Isabelle Faust and Alexander Melnikov to start recording 19th-century violin/piano repertoire on period instruments? At this point, who cares? The conceit has resulted in a string of interesting (if, sometimes, slightly strange) albums for Harmonia mundi, but their latest – pairing Cesar Franck’s Violin Sonata and Ernest Chausson’s Concert for Piano, Violin, and String Quartet – is a wonder.

Faust’s performance of the Franck’s solo line is entrancing. Her gut-stringed Stradivarius projects robustly enough in the big moments, but she’s at her finest during the quieter bits. Here, the hushed intensity of her playing, combined with spot-on intonation and judicious vibrato, crafts an atmosphere of passion and mystery.

For his part, Melnikov, playing a mid-1880s Erard, turns in a warm, fluid reading of the non-stop piano part. The balances between the keyboard’s foreground and background materials are always handled with delicacy and the rhythmic energy of Melnikov’s playing never lets up.

The Chausson, too, benefits from the duo’s concentrated approach. It’s a curious piece by just about any measure, part double-concerto, part piano sextet. Chausson’s writing in it is lyrical, sparkling with color, and hinting, at times, at the styles of Debussy and Ravel. For sheer, gracious charm, you’d be hard-pressed to beat its second-movement “Sicilienne,” and, while the third-movement “Grave” forms the score’s emotional heart, the sweeping, impellent drama of the outer movements is downright symphonic.

Faust and Melnikov, who hardly get a breather in the forty-minute piece, revel in its cascading flourishes and Gallic restraint. The same focused tone and affectionate phrasing they brought to the Franck successfully transfers to the Chausson. They’re joined here by the Salagon Quartet, who provide a satisfying accompaniment.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Alexander Melnikov, Harmonia Mundi, Isabelle Faust, RCA Red Seal