Visual Arts Review: An Impressive Selection of Picasso Prints at The Clark

This is a relatively small but stunning selection of Picasso’s finest prints, a collection that reflects the artist’s range of inspiration.

Picasso: Encounters at the Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, through August 27.

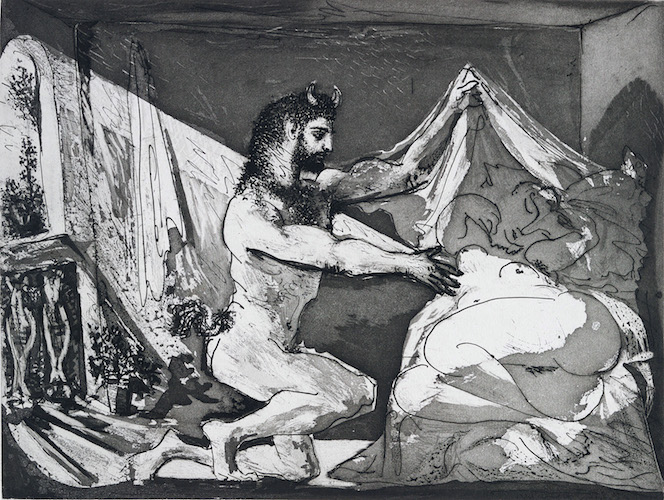

Pablo Picasso, “Faun Unveiling a Sleeping Girl” (1936). Photo: courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

by Charles Giuliano

Until recently, the special exhibitions of the Clark Art Institute reflected the taste of Sterling and Francine Clark, who focused on Impressionists and nineteenth century masters.

The 2010 exhibition The Genius of Renoir and 2015′s Van Gogh and Nature sustained the commitment to impressionist and post impressionist blockbusters. The Clark, however, saw that it could expand audiences by gradually moving into showing the work of modern and contemporary masters. A transitional project on the cusp of impressionism and modernism was the 2010 exhibition Picasso Looks at Degas.

The Tadeo Ando expansion created two exhibition spaces both large and intimate in its new wing and galleries in its Stone Hill Center. The museum is no longer confined to one major exhibition during high season. Its programming this summer suggests what we can expect in the future from one of the nation’s foremost regional museums.

Remaining true to its nineteenth century mandate, while augmenting The Clark’s permanent collection, there is Orchestrating Elegance: Alma-Tadema and the Marquand Music Room. This show runs in tandem with an exhibition of prints — Picasso: Encounters. Both are in the new wing. Opening in early July, at the Stone Hill Center space, works by the color field painter and printmaker Helen Frankenthaler will be featured.

Surprisingly, as Clark curator Jay A. Clarke commented during a media tour for the Picasso show, the exhibition builds on a work from the institution’s holdings. Some time ago a seminal print, The Frugal Repast (1904), from the artist’s acclaimed Blue Period, entered the collection. Clarke felt that the picture was lonely and could use some company.

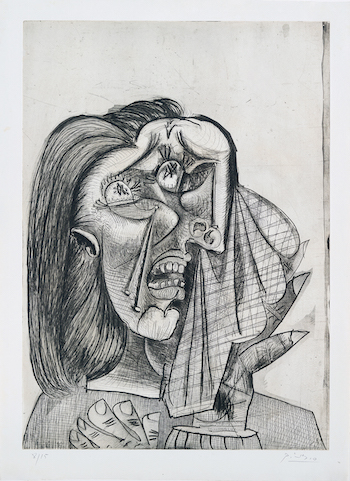

The Weeping Woman,” drypoint, aquatint, etching and scraper, 1937, private collection, courtesy of Clark Art Institute.

And it has gotten some impressive neighbors. In Picasso: Encounters Clarke has assembled a relatively small but stunning selection of the artist’s finest prints, a collection that reflects the artist’s range of inspiration. They are enhanced by a few choice paintings, such as 1901’s singular Self Portrait (with its surprising helmet of hair) from the Musee national Picasso-Paris. The menacing artist stares at us with Spanish machismo aplenty, defying his lowly status as a starving artist in Paris. The somber blue background literally tells that he is overcoming the blues.

In that same year Picasso painted his first masterpiece, The Blue Room, which depicts a blonde woman bathing in a metal tub that sits in his shabby studio/residence (his first) in the dilapidated artists complex Le Bateau-Lavoir (“The Boat Wash-house”). [The nickname for a building in the Montmartre district of the 18th arrondissement of Paris.] Little is known of her, but she was the first of many live-in mistresses.

As a bachelor in Spain Picasso only knew prostitutes. The unconventionality of French women surprised him; he retained the sexist dogma that a woman was either madonna or a puta. A parade of renowned muses cavort through his work, inspiring its periods, styles, and innovations. Knowing Picasso’s women is essential in understanding the artist’s work.

They begin with Fernande Oliver, a bohemian who loved big hats and cheap perfume. She was his muse during the Blue Period and into the era of analytical cubism. Eventually, she tired of having to live under lock and key and had an affair with another artist. She left in 1912.

Not long after that Picasso was involved with the “love of his life,” Marcelle Humbert, known as Eva Gouel (1885-1915). There is a hint of her in the synthetic cubist painting (1911-12) “Ma Jolie.” The title was a refrain in a popular song as well as the artist’s nickname for Humbert. From that era, the Clark exhibition displays Still Life with Bottle of Marc, a drypoint from 1912.

The success of cubism made Picasso rich and famous. He then married the minor Ballets Russes dancer Olga Khokhlova. He met her in Rome during WWI when working on Diaghilev’s 1916-1918 ballet Parade. Picasso was essentially a draft dodger (technically he was not a French citizen). His partner George Braque enlisted and they were estranged after the war.

To please the demanding Olga, he explored an accessible, neo-classical style, exemplified in this exhibition’s lyrical but conservative drypoint, 1923’s Olga in a Fur Collar.

Friends were surprised when a blonde woman appeared in his work. Marie-Thérèse Walter was an athletic teenager he encountered on the streets of Paris. He waited for her after school; and he eventually installed his secret mistress in an apartment. We encounter her classical profile in the 1928 lithograph Visage (Face of Marie-Thérèse). Walter inspired such cubist masterpieces as the 1932 painting Girl Before a Mirror.

On April 16, 1937, under orders of Generalissimo Francisco Franco, German stuka dive bombers devastated the town of Guernica in the Basque region of Spain. In a frenzy, Picasso created the epic painting Guernica by June. Surrealist photographer Dora Maar documented the work-in-progress daily. Of all of Picasso’s women, she was the best match for him as an artist and intellectual.

Maar remained in competition with Olga, to whom Picasso remained married and supported until her death in 1955. Fading Marie-Thérèse remained in the mix as well. Maar was beset by jealous fits — depicted in the artist’s cruel and grotesque Weeping Woman series of paintings and prints. There are four daunting drypoints (from 1937) of these disturbing images. The exhibition also includes, from the same year, a less roiling (actually, charming) cubist painting of her.

“The Frugal Repast” etching and engraving, 1904, collection of the Clark Art Institute.

The minotaur, a mythic beast half human and bull, served as an archetypal totem for Picasso. The animal/human is a paradigm of primal machismo, of blood and sand, of Spain’s appetite for violence and testosterone. Triumphs in bed and the arena inform many of the artist’s works.

This exhibition includes both his iconic ‘rough beast’ print Minotauromachia (1935) and the seductively lyrical Faun Unveiling a Sleeping Girl (1936) from the magnificent Vollard Suite. These rich and complex works combine etching, engraving, and sugar-lift aquatint. They give us the artist at his most viscerally powerful and intently experimental.

Over his lifetime he worked with a number of artisans, collaborators, and printers. It is the task of scholars to examine how much he owed to each of them.

Under German occupation in 1943 he met the 21-year-old art student Francois Gilot, who was later the mother of Claude and Paloma. After ten years together she left him and later wrote a nasty book about the artist, My Life With Picasso. He had fun with his kids — until they grew up. It is easy to sense that cooling off in 1952’s dyspeptic lithographic portrait of Paloma.

Picasso’s last woman and second wife, Jacqueline, served as his caregiver, collaborator on prints and ceramics, and firm gatekeeper. She kept him isolated, aside from meetings with well vetted friends. Finally, she presided over the utter mess of his estate.

Charles Giuliano is publisher/ editor of Berkshire Fine Arts. He will soon publish his fourth book since 2014, Gloucester Poems: Nugents of Rockport. This summer he will jury the annual show for Boston’s Galatea Gallery.

Tagged: Charles Giuliano, Clark Art Institute, Picasso Prints, Picasso:Encounters