Book Review: Gershom Scholem — A Rich and Complicated Jewish Life

On balance, George Prochnik’s biography of Gershom Scholem is flawed, but well worth reading, especially for those struggling with their Jewish and Israeli identities.

Stranger in a Strange Land, Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem by George Prochnik. Other Press, 528 pages, $27.95.

By Roberta Silman

Gershom Scholem is an important figure in 20th Century Jewish history and a hero of my dear friend Ira Berkowitz, so when I received Stranger in a Strange Land there was no question that I would review it. I began with a skeletal knowledge of Scholem, who had been born Gerhard Scholem in Berlin in 1897. He had changed his name to Gershom — meaning “stranger in a strange land” in Hebrew — when he emigrated to Jerusalem in 1923. He had an eminent career as an academic in Palestine, then Israel, had fought with Hannah Arendt over her reportage of the Eichmann trial, and has also written a fascinating and “authentic” (his word) biography of his oldest and most important friend, Walter Benjamin, who is one of my heroes.

However, Scholem was also a name I knew from childhood. As the son of an Orthodox Rabbi who was a Talmudic scholar and as a man who struggled with his own relationship to God and the Jewish religion, my father was interested in Scholem; he once suggested that instead of majoring in English literature and the Classics I should be studying Jewish mysticism in college. It was out of the question at the time. But now I understand my Dad’s fascination with Scholem’s work on the Kabbalah, for here was a very brave man, a man who was not afraid to articulate the failure of conventional Judaism to bridge the gap between God and man. Or in Scholem’s words, to find an answer to the sad fact that “Religion’s supreme function is to destroy the dream-harmony of Man, Universe and God, [creating] a vast abyss, conceived as absolute, between God, the infinite and transcendental Being, and Man, the finite creature.” Moreover, he had the courage to come up with an answer. As Prochnik explains it,

Mysticism, according to Scholem, acknowledged the existence of the abyss, then embarked on a quest for the hidden bridge that might span this gap. Confronting the rupture between man and God engendered by the religious cataclysm, mysticism strove to piece together the shards, — then continuing in Scholem’s words — “to bring back the unity which religion has destroyed, but on a new plane, where the world of mythology and that of revelation meet in the soul of man.”

This is an enormous task, on which Scholem worked all his life; his belief that Hebrew is the only language capable of revealing divine truth informed all he did, including his need to go to Palestine as a young man; his scholarship is profound and regarded with great respect by such scholars as Cynthia Ozick and Harold Bloom, and he has influenced writers as different as Borges and Umberto Eco and Derrida and Michael Chabon. Not only his work deserves our attention; his life is in and of itself a fascinating 20th century journey: his decision to leave Germany when he did, his close but sometimes frustrating relationship with Benjamin, his views about socialism and Zionism, his stance on the struggle to make Israel a state, and his reaction to the Holocaust and all the complications of being a citizen of Israel after the Second World War are all worth reading about.

The problem is that this biography is a dual one — not only of Gershom Scholem, but of George Prochnik. And here is where the trouble starts. As I have said before, most recently in my review of Edmund Gordon’s biography of Angela Carter, writing a biography is hard. I have compared it to a long marriage — for the research sometimes takes several years — and one can also compare it to a demanding love affair in which the author’s needs and wants are put aside. It requires great focus and dedication. Which may be too much for some writers. Indeed, there seems to be a new kind of biography emerging in American letters where the author inserts himself in very real ways, adding a kind of parallel universe to that of the main subject of the biography. Although I have not yet read it, this is what Megan Marshall has done in her new biography of Elizabeth Bishop, who was her teacher at Harvard, and it is what Prochnik does here. He tells us about his early life in Virginia as a child of a Christian mother and a Jewish father, his search for meaning in life, his discovery of Scholem, his connection as a young husband with a synagogue composed of mostly Holocaust survivors in Manhattan, and his sojourn in Israel with his first wife Anne as they struggled to find a place for themselves in the Israel of the late 1980s and 1990s while bringing up four young children.

As interesting as this may be for Prochnik and as sincere as he may be, these sections of the book simply did not work for me. They interrupted the thread of Scholem’s story and veered from sophomoric to annoying, especially when it became clear that Prochnik’s ability to earn a living and his marriage were both fraying. He comes across as someone who at that time had no problem-solving skills and complained a lot, so it was no surprise that he and Anne were contemplating divorce when they decided to leave Israel and come back to the States shortly before 9/11. It may say more about me than about them, but their travails left me cold. It was Scholem who had captured my interest.

And it is Scholem and the rich history that forms a backdrop to Scholem’s life that Prochnik does so well. We learn about his problems with his family, especially his father, Arthur; his devotion to his older brother Werner, who was a Communist, his struggles with German authorities to avoid military service during World War I, his sojourn to Switzerland where he became disillusioned with Benjamin and his wife Dora, and his years in Munich when he finally finished his degree before going to Palestine. Prochnik is an ambitious writer and not afraid to untangle a very complicated, but also very intellectual and, in many ways, solitary life (which is what he did earlier with Stefan Zweig in his book The Impossible Exile, which is next on my list of books to read).

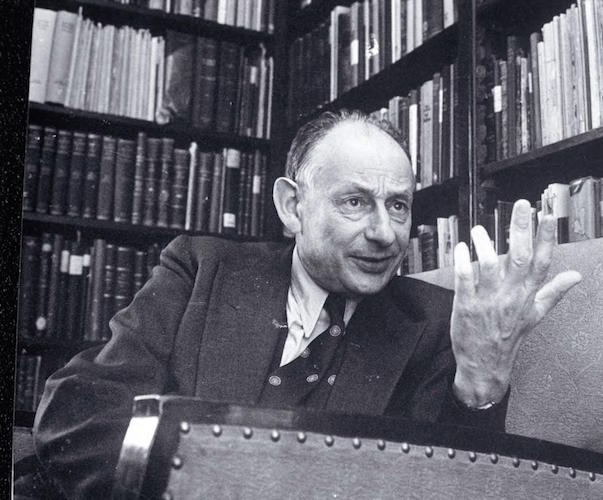

Gershom Scholem — his scholarship is profound and regarded with great respect by such scholars as Cynthia Ozick and Harold Bloom.

As a result, he braids, seamlessly, Scholem’s research on the Kabbalah with Middle East history, or Scholem’s way of looking at subjects like the Shekinah, the possible feminine attributes of God, or the Book of Jonah in new and surprising ways. He brings in various salient figures with great skill, like Weitzmann and Buber and Judah Magnes, who favored a binational solution before anyone else. His telling of such historical events as Balfour’s visit to Palestine in 1925 and the Arab riots during the summer of 1929 have real tension, as does his description of Scholem doing the research on what would become one of his most important works: his book on Sabbatai Zevi.

Captivated by the man, Prochnik also conveys Scholem’s impishness, his curiosity, and his immense intelligence. We learn about Scholem’s love of Walt Whitman, and the importance of Kafka’s work in his life, as well as more personal details, such as his everlasting grief at Benjamin’s suicide in 1940, his fading love for his first wife Escha, and his marriage to Fanya, a relative of Freud who became his second wife. Some of the accounts about Scholem from Ozick, Bloom, and Hans Jonas are wonderful, and the recreation of Scholem’s meeting in Paris with Allen Ginsburg is, literally, priceless. I wouldn’t have missed them for the world.

So, on balance, we have a book about Gershom Scholem that is flawed, but well worth reading and owning, especially for those of us struggling with our Jewish and Israeli identities, or with the question of how to hand on to our children and grandchildren those ineffable but very real qualities that we so cherish, that “make us Jewish.” And although there are many places where I stopped to admire Prochnik’s exegesis of Scholem’s ideas, I will close with this one that comes about half-way through the book:

If kabbalistic practice had once helped reconcile the Jews to exile by contextualizing the people’s homelessness within a divine scheme, knowledge of the Kabbalah might now help to fuel a creative awakening around the idea of the exile’s conclusion—reminding Jews of historical energies and radical spiritual desires they’d repressed for centuries. In this sense, Kabbalah functioned for Scholem on the national plane a bit as the id did for Freud on the personal level: It wasn’t that he felt one should unleash such forces unchecked on the world. Scholem didn’t tell people to go out and become Kabbalists. But the powers of Jewish mysticism, if simply bottled up inside, distorted and deadened Jewish identity. One had to understand what was happening in the depths of the national self in order to free up its potential of dynamic growth.

This quotation gives you an idea of what is at stake here. Thus, we must be grateful to George Prochnik for giving us all this interesting material about this fabulous Jewish scholar who surely deserves to be better known.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: George Prochnik, Gershom Scholem, Other Press, Searching for Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem

Shalom & Boker tov…you present a cogent overview of George Prochnik’s effort, which I read with keen interest, and some degree of disappointment I share with you regarding his hyperbole. For an exhaustive, brilliant exploration of Reb Scholem:

Amir Engel, 2017. Gershom Scholem: an intellectual biography (Univ. Chicago Press), 1-226

STEPHAN PICKERING / חפץ ח”ם בן אברהם

Torah אלילה Yehu’di Apikores / Philologia Kabbalistica Speculativa Researcher

לחיות זמן רב ולשגשג

THE KABBALAH FRACTALS PROJECT