Visual Arts Review: “Botticelli and the Search for the Divine” at the MFA

This is the largest exhibition of Botticelli paintings ever mounted in North America. Bigger may not always be better, but this is a gorgeous show.

Botticelli and the Search for the Divine, on view at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston through July 9.

“Nativity,” about 1482-1485, Sandro Botticelli. Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Photo: courtsey of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

By Kathleen Stone

If you go to the Brancacci Chapel in Florence and look to the right, you will see St. Peter being crucified. A crowd of men watches but one, with long hair and a cheeky expression, turns to face the viewer. That’s the artist Sandro Botticelli when he was beginning to make a name for himself in the workshop of Fra Filippo Lippi. Further to the right is a scene that takes place in front of the Emperor Nero; another young man looks directly at us. That’s Filippino Lippi, son of Fra Filippo, a student of Botticelli and painter of both frescoes.

By the time Lippi painted Botticelli into the crucifixion scene, in approximately 1485, Botticelli was in his forties and in the midst of producing his most acclaimed works: The Birth of Venus, Primavera, Minerva and the Centaur and wall paintings in the Sistine Chapel. He, like many other Florentines was a student of antiquity and worked to create a harmony — often through the means of allegory — between Greek and Roman myths and the teachings of the Catholic Church. For a time, the Church tolerated such a humanistic outlook. That peaceful co-existence was shattered, however, when Lorenzo de’ Medici, a champion of humanism, approached the end of his life and Girolamo Savonarola, the Dominican friar, began preaching against the excesses of Medici rule and secular wealth. Botticelli became enbroiled in the controversies that roiled Florence and his art became a barometer of the city’s intellectual and religious life.

Botticelli and the Search for the Divine is the largest exhibition of Botticelli paintings ever mounted in North America. Bigger may not always be better, but this is a gorgeous show. The painter’s colors alone make it worthwhile — cinnabar reds, malachite greens, lapis lazuli blues. The ethereal gold edging of veils and haloes remind us that Botticelli first trained as a goldsmith. In his delicate hand, paint takes on a shiny transparency, a gold gossamer.

Seeded with twenty-one paintings on loan from Italy as well as local masterpieces from the MFA, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and the Harvard Museums, the show focuses on the context in which Botticelli painted. It opens with a Virgin and Child (1466-69) by Fra Filippo Lippi that is striking for its warmth and tenderness. The Virgin holds her baby with two hands, one cupped behind his head, and presses his face to hers, his chubby cheek merging against her slender bone structure. It’s an expression of maternal love, as secular as it is religious. At about the same time Botticelli painted his Madonna of the Loggia (1467), and that picture shows that he paid attention to his teacher; Botticelli’s mother and child are bound together in a similar tender pose.

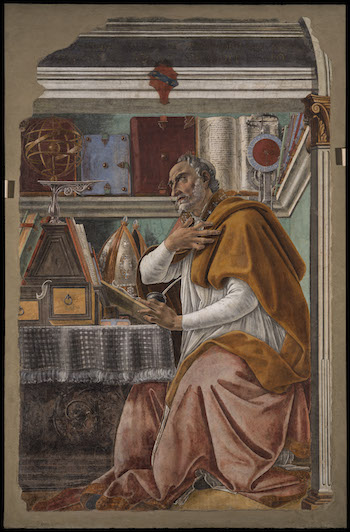

“Saint Augustine in his Study,” about 1480, Sandro Botticelli. Church of All Saints (Ognissanti). Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Botticelli went on to become master of his own workshop where he raised the level of his expertise and began a deeper exploration of the meaning behind his work. Madonna of the Book (1478-80) is an exquisite example of the finesse with which he could paint, but it also trains a more intense gaze on the religious nature of his subject. Jesus in his mother’s lap points to a passage of holy text and looks up at her, anxious to engage her attention. Tiny golden nails and a ring of thorns around his wrist foretell his future crucifixion. The Madonna, draped in a gorgeous deep blue robe, looks down and avoids his gaze. She seems more passive than her infant son, a sign, perhaps, that Botticelli was more interested in the divine than the secular experience of motherhood.

Botticelli created his most famous works, full of classical subjects and allusions, in the 1480s. Minerva and the Centaur originally hung next to his Primavera in a Medici palace; his Birth of Venus was also a Medici commission. In each, a beautiful young woman appears in the guise of a Roman goddess, either to extoll a humanistic value or embody the idea of divine love. In Minerva, the only one of the three paintings in the Boston show, there is a coolness of tone. Minerva has placed her hand on the centaur’s head, but the two figures have withdrawn into themselves; it’s hard to feel there’s any connection between them. If she has triumphed over the chaos and lust that the centaur represents, as text on the wall suggests, she has done so without any apparent struggle, anger, or aggression.

St. Augustine in His Study, a large fresco originally created for the Church of the Ognissanti in Florence, gives us philosopher and Christian theologian Augustine in his study, surrounded by implements of both religious and secular life — a bishop’s mitre, a geometry text, an astrolabe for measuring the altitude of celestial bodies — symbols of the conflict between faith and the intellect. Augustine is a massive figure here, shown clutching the robe over his heart as he composes texts to integrate the Neoplatonism of his youth with the strains of Catholic thought that were prevalent when he converted in the year 386. Botticelli would have been conversant with Augustine’s influential Church writings: the desire to integrate humanism with theology — and quell the struggle between the two — that would play out in spectacular fashion in Botticelli’s time.

By the 1490s, Florence was becoming unglued. Savonarola had prophesized the city’s destruction, and when Charles VIII of France invaded it must have seemed as though the friar’s predictions were coming true. The Medici family, who had ruled for a nearly century, went into exile and the streets were patrolled by squads of Savonarola’s adherents, who browbeat wealthy citizens into forsaking their material possessions. In 1497, when the bonfire of vanities burned, Florentines heaped books, cosmetics, mirrors, and other luxuries onto the flames. A year later, Savonarola himself was arrested, tortured, excommunicated, and burned.

“Minerva and the Centaur,” 1444 or 1445-1510, Sandro Botticelli. Uffizi Gallery. Photo: courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

How did Botticelli react? An adherent of Savonarola, he is believed to have burned some of his own paintings, perhaps nudes. It should not be surprising that the upheaval seems to have scarred his world view. His post-Savonarola paintings are darker in color and tone, their landscape settings increasingly barren. Mystic Crucifixion (c. 1500) shows Mary Magdalene shrouded in a scarlet robe, clutching the foot of the cross with an angel standing over her, about to slay the heraldic lion. The city, shining in sunlight, is in the far distance; more immediately, a swirling, jagged rock formation hovers over the figures, as though it is about to swallow them up. Here, Botticelli is animated by a fervor notably absent from his earlier paintings.

He continued working with the subject of Madonna and Child, and two late paintings show changes in his approach to that well explored theme. In one, the Virgin is handing the baby Jesus to his cousin John for a kiss. She is tall, and has to bend herself in half; the posture makes the picture look surprisingly edgy. Plus, there is a brown tint to her blue and red robes and the folds lie flat. Compared to his earlier work, particularly Madonna of the Book, or even Minerva and the Centaur, it’s a darker, less luminous picture.

At this point in his career, the young man from the Brancacci Chapel is older and battle scarred. He used to be “a man of pleasant humor, often playing tricks on his disciples and his friends,” writes Giorgio Vasari, the art biographer. Now Botticelli has survived to reflect on the cataclysmic convulsions of his era.

Kathleen Stone lives in Boston and writes critical reviews for The Arts Fuse. She co-hosts a literary salon known as Booklab and is at work on several long projects. She holds graduate degrees from the Bennington Writing Seminars and Boston University School of Law, and her blog can be found here.

Tagged: Botticelli, Botticelli and the Search for the Divine, Kathleen Stone