Poetry Review/Interview: Poet Martín Espada — Resistance is Obligatory

Martín Espada’s lyricism sings deeply in the key of loss, turning the anguish of social and personal histories into hope.

By Matt Hanson

As the dismal state of left-wing politics makes clear, it’s time to hit the books and then some. The left needs to revitalize what has become its increasingly effete approach by reclaiming the language of protest and reestablishing its historical connection with the working class. Now more than ever we need to listen to poets who see it as their job to voice suffering, to make it vivid and unforgettable on the tongue, to put front and center the struggles of those who Walt Whitman once called “the numberless unnamed heroes equal to the greatest heroes known.”

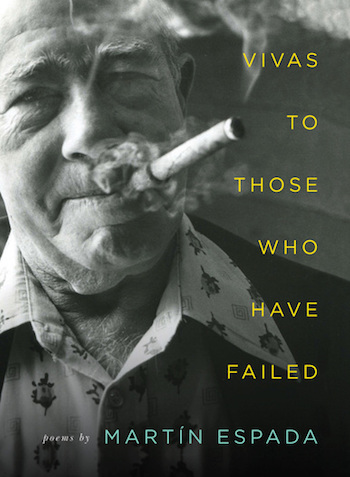

In his fourteenth book, the acclaimed poet and activist Martín Espada takes on a dual role, fusing the personal and the political: these poems celebrate the courage that has driven labor’s struggle for justice while painfully sorting through losses of family and friends. The poems in Vivas to Those Who Have Failed are thoroughly annotated, providing a useful immersion in the kind of history that they still don’t teach you in school. Espada’s lyricism sings deeply in the key of loss, turning the anguish of social and personal histories into hope.

A series of sonnets in honor of the Paterson Silk Strike, where thousands of workers marched for an eight-hour workday, opens the book. The poems spotlight the experiences of organizers who ought to be better known, such as John Reed and Carlo Tresca, the leader of the powerful Industrial Workers of the World. Perhaps as affectingly, the poems offer posthumous tribute to the thousands who walked out of their factories one day in 1913, shutting down three hundred mills in Paterson, New Jersey, their names and faces “rubbed off/ by oblivion’s thumb like a Roman coin.” Though the strike failed and the police’s “nightsticks cracked cheekbones like teacups” the demands for a livable wage and a fair work week could not be ignored and would reverberate throughout the history of American labor.

You can hear the contemporary echoes of police brutality in the poem “How We Could Have Lived or Died This Way,” in which the poet fixes his dry-eyed but deeply empathetic gaze on the recent wave of police brutality: “I see the dark-skinned bodies falling in the street as their ancestors fell/ before the whip and steel, the last blood pooling, the last breath spitting.” The poem vividly records the gruesome facts on the ground, propelled by a humane commitment to witness: “I am in the crowd, at the window,/ kneeling beside the body left on the asphalt for hours, covered in a sheet.”

Espada writes of lives jarringly colliding with history. In “Ghazal for a Tall Boy from New Hampshire” he pays tribute to Jim Foley, a former student of his, a teacher of English himself, who was videotaped being beheaded by ISIS. The press asks him for a quote, but instead of feeding the need for hype and hysterics, he calmly directs us to the work Foley did teaching “the refugees from an island where the landlords/ left them nothing but their hands. In Spanish, they knew him.” Espada’s political vision is built on a rock solid foundation: a profound belief in the reality of others and the power of human relationships.

Thankfully, there’s nothing shrill or self-righteous about Espada’s critique. A refreshing current of wit runs through the book. One poem juxtaposes performing in a Shakespeare play set in the summer of love with an anecdote about a replica of Machu Picchu that’s made out of Rice Krispies Treats. Sitting in Fenway Park during a Red Sox game, the poet contemplates the crowd’s mad scramble for a ball hit towards the stands. Espada sees a woman catch it and then give it to a boy. He endearingly admits that “bad socialist that I am, I would have kept it.”

The elegy for his mentor and friend Howard Zinn gives us the legendary historian in an ordinary situation. Zinn and Espada stand at the top of icy stairs. Zinn has “nothing to say for once.” Instead of going back inside, the elderly writer takes a bucket and throws “a handful of sand in the air like bread for pigeons” and delicately feels his way down, step by step, becoming an image of progress and determination that will “turn the tundra into the beach with a wave of his hand…showing the way across the ice and down the hill into the street.” His last words in the poem are a commonplace that turns into an affirmation: “you drive.”

The collection ends with a series of linked poems written in memory of the poet’s father, Francisco “Frank” Espada, a larger than life, Puerto Rican-born Brooklyn union organizer and documentary photographer. The poems celebrate the man’s fierce tenacity and pride, illustrated by his fighting off racist police to being jailed in the segregated South, “his Air Force uniform all that kept the noose from his neck.” Frank Espada, “a mountain born of mountains,” delivered speeches alongside Malcolm X, dodged bullets and falling concrete on the streets of New York, made peace during riots, and doggedly photographed the faces of the Puerto Rican diaspora when Cornell Capa told him that “no one wants to look at pictures of Puerto Ricans.” He spent his life arguing on behalf of a community that is still sadly under intense pressure.

The moving eulogy “El Morivivi” is inspired by a Puerto Rican flower that is sensitive to the touch: it opens with the sun and closes at night. Its name can be translated as “I died, I lived.” Frank Espada’s vibrant, unapologetic life is memorialized through sharply-etched detail and loving admiration; the poems make the hard work of activism and advocacy come off as noble and dangerous and inspiring. At the end of one of the elegies, Espada pushes the chair away from the table and calls for his father’s ghost to “Sit down. Tell me everything. Haunt me.” There isn’t any doubt in the reader’s mind that being haunted has become a very valuable thing.

The Arts Fuse sat down with Espada at his home in Amherst, MA (he teaches at the University of Massachusetts Amherst), to discuss (over the occasional interjections of two Pomeranians) his vivas, W.H. Auden, the current political landscape, the movie Paterson, and what poetry makes happen.

Arts Fuse: The title of your book is Vivas To Those Who Have Failed. It’s obviously a Whitman quotation, and an interesting one because it’s not the kind of thing usually associated with Whitman.

Martín Espada: The phrase, “Vivas to those who have failed,” indicates that Whitman is celebrating those we define as defeated, insisting that we look at history differently. He is insisting that we redefine what we mean by the word “failure.” In “Song of Myself,” there are places where Whitman acts as advocate for the damned and despised—those who are damned and despised again, today, in the age of Trump. I take my cues not only from section 18 of “Song of Myself”—the source of this quote—but from Whitman’s empathy as a whole.

I take my cues also from others who see history this way. I was close to Howard Zinn. There is a poem about Howard in this book, my second poem about him. I was deeply influenced by Howard’s way of seeing history. Howard had a great gift for taking a nugget from the past, holding that nugget in his hand, and saying, “See: look at the way this shines.” He was always able to find examples from history to prove that indeed, resistance is not only possible, but obligatory.

AF: Your father, the late Frank Espada, appears throughout this book. The cover is a photograph of his. Could you talk about his life and activism as it relates to this book?

Espada: My father was a community organizer and activist, a leader of the Puerto Rican community in New York, and a documentary photographer, who created the Puerto Rican Diaspora Documentary Project, which resulted in more than forty one-person shows and a book by the same title. (His works are included in the collections of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, the National Portrait Gallery and the Library of Congress.) When my father died, I took on the responsibility of writing a poem for his memorial service in Brooklyn. I sequestered myself in Northern Vermont and, instead of writing one poem, I wrote ten. That is the cycle that appears at the end of this collection.

I’m saying to him, or for him, “Vivas to those who have failed,” because my father looked at the political landscape at the end of his life and said, “I failed. We failed.” We should remind ourselves, but also remind those who took part in that struggle that they did not fail, that we honor their struggle, that those “failures” led to real change. When we take to the streets or write poems, it’s a way of paying homage to those who came before us.

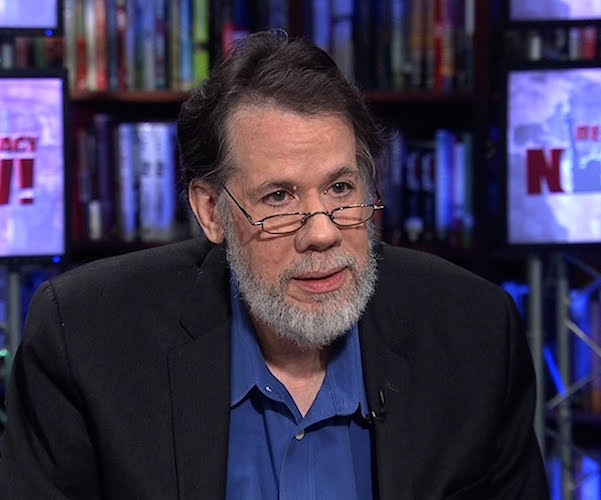

Poet Martín Espada

AF: You’ve done a lot of activist work and you were once a tenant lawyer in the Boston area. I’m curious about what you would say, as a poet, about how poetry relates to structures of power. What is the relationship between the verse and the power structure, writ large?

Espada: I’ll quote my friend, the historian Marcus Rediker, who has said: “Injustice depends on abstraction.” He has a way of distilling things. Injustice depends on abstraction. We can talk about abstractions like “infrastructure” or “power, but my job as a poet is to make the abstract concrete. My job is to tell stories as vividly as possible, to ground the narrative in the image, the language of the senses, so you can hear it and taste it and touch it and smell it. Thus, thinking about the relationship between poetry and power compels me to think about craft, about making the best poem I can, so that it might move hearts and minds.

Can I quantify the impact of the poem in the world? No. I cannot. I’d lose my mind trying to do that. The impact of a poem cannot be weighed, measured, labeled, or boxed. I put the poem in the world, up into the atmosphere we breathe. That poem is, paradoxically, an act of faith.

AF: When I think about that kind of faith, I’m always reminded of the famous quote from W.H. Auden: “poetry makes nothing happen.”

Espada: Poor Auden. Let’s be clear: I think the quote has been misused, taken out of context. When we quote Auden as saying, “poetry makes nothing happen,” it sounds wise. Yet, Auden was addressing a complex set of issues in his own time. Moreover, despite his protestations, he wrote political poems. His poem “September 1, 1939” made the rounds after 9/11 for that reason. It provided consolation for people because it spoke to a certain hope. Now, when people say, “poetry makes nothing happen,” lacking context, it is often used to justify apathy, to justify indifference. Intellectuals are very energetic when it comes to justifying their apathy. I have seen the effect that poetry can have on communities or individuals in dire conditions. There are ways that poetry reaches and speaks to them.

AF: Changing gears a little bit, I wonder if you’ve seen Paterson, the Jim Jarmusch film about the bus driver poet in Paterson, NJ. What did you think about that?

Espada: I did see it. I’m actually familiar with the city of Paterson and what I didn’t see in Paterson was Paterson. I know it was filmed there, but Paterson is a city with a very sizeable Latino population, which, with two very brief exceptions, did not appear in the film. There is one scene where some stereotypical gangbangers pull up in their car and ask pointed questions about the hero’s dog. I’m tired of seeing tens of millions of people in this country treated as if they barely exist. Donald Trump knows very well that they exist, and he’s trying to get rid of them.

I really like some films by Jim Jarmusch, such as Ghost Dog and Dead Man, but he should have acknowledged the fact that Paterson is Paterson. There are so many Latinos in Paterson, the city; it was quite strange to see barely any Latinos in Paterson, the movie. There’s a myopia, reflected in the media and the culture at large, reflected in the movie. We need to hear more Latino voices and see more Latino faces. There’s a phrase in Spanish, “Aquí estamos y no nos vamos,” meaning, “here we are and here we stay.” When I see a program on CNN or MSNBC, with a panel on immigration, and there are no Latinos, I have to wonder why.

I was disappointed with Paterson. Jarmusch had a good premise, with interesting characters, yet he takes this equally interesting city and reduces it to a colorful backdrop. If he had asked me, I would have told him: if you make a movie set in Paterson, you’ll need plenty of Puerto Ricans and Mexicans. I’ve given so many readings there. I’ve visited so many schools there. I’ve had children and adults write poems for me in workshops. They have stories. They have realities. This goes beyond Jim Jarmusch. This is about the invisibility of Latinos in mainstream culture. That is symptomatic of a larger problem, a larger absence.

AF: I was going to ask you about what’s at stake in the culture during the age of Trump, with his consistent fear mongering and scapegoating, particularly about Mexicans.

Espada: There are plenty of reasons to loathe Donald Trump, but, beyond Trump, we must bear in mind that an entire group of white nationalists on the right, in their efforts to whiten America, now have the upper hand. They intend to subtract and erase millions of people who are brown and/or speak Spanish. There’s an effort to do that on a scale unprecedented in recent history. While they’re trying to impose a Muslim travel ban, Trump and friends are also carrying out plans to build a wall or a fence or whatever on the border, which would turn the border into a police state.

To do what they want, they will have to incarcerate many people. They will have to build and staff those facilities. There will be no more “catch and release;” there will be incarceration. They will create a criminal record for undocumented people, so they can point to that record and say, “Look, criminals!” Trump got elected through scare tactics, fear mongering, selling the image of immigrant as criminal. To convince the majority that this is a reality, he must broaden the definition of criminality, must criminalize the very existence of these immigrants.

The perception of dangerousness is dangerous. Trump demonized immigrants from day one of his candidacy. He demonized Mexicans as drug dealers and rapists. Not long afterwards, in Boston, two brothers, the Leader brothers, returning home after a Red Sox game, came across a homeless Mexican man. They woke him up by urinating in his face. They beat him severely with a pole, breaking his nose. (They received relatively light sentences.) When the police arrested them, one of the brothers made the link, saying that Donald Trump was right. He made his motivations very clear, and when Trump was asked about this he said that his supporters where “passionate.” Why isn’t that story being told more often? There have been plenty of hate crimes reported, but there’s the one that sticks with me. People can point to this brutality and say that it’s isolated, but the principle applies: the perception of dangerousness is dangerous.

Whenever I give readings, whether they’re politically themed or not, I turn to the subject of immigration. I believe that poetry humanizes in the face of dehumanization. I believe that poetry can insist upon the dignity of human beings denied that dignity; that poetry can insist upon respect for human beings denied that respect. I have plenty of poems to read about the damned and despised.

AF: There are quite a few elegies in this book, not just to your father. Could you speak to that?

Espada: If you lose someone close to you, you may find yourself talking to that person. You may feel a profound absence, and speak to that absence. When you speak to that absence, in effect, you keep that person alive.

AF: And that’s about being a witness, that’s about keeping something alive.

Espada: Yes. I can speak to my father, and speak to that history as well. That’s an intimate, personal form of address. Anybody who reads my work knows that I am a Puerto Rican poet. I write about being Puerto Rican. I write about the history, about the family. But the fact that I have a multiplicity of identities should also be apparent. I believe in justice for people beyond my own community. I have a class analysis that goes beyond my understanding of racial politics or identity. My father, who was Puerto Rican to the bone, believed very strongly in building coalitions.

My father understood that, as a community organizer in Brooklyn in the 50s and 60s, he had to build coalitions in order to be politically effective. If he confined himself to his own community, he would be defeated. My father reached out and built coalitions, particularly with the African-American community in Brooklyn. You have to build coalitions, build bridges, reach out to people who are different from you and yet have something in common with you: the need for profound social change. How do you communicate with those people? That’s the essential question.

AF: So if there was ever a time for poetry to humanize people…

Espada: This is it. We need people who haven’t started thinking things through to start thinking things through. Reaching beyond? I do that all the time. I do that because my work, first of all, strives for a clarity that makes it possible. I also do that because I take poetry to so-called non-traditional places, which are, in fact, the most traditional places of all, if you consider the roots of poetry as an oral art form. Last Christmas Eve, I did a reading at the Franklin County Jail in Greenfield, Massachusetts. To poets out there, I would say: go and do that. Go to a prison. Take your work there. ake your work into inner city high schools, whether they’re paying you or not. Don’t just show up at the door. Do it right. But do it. Organize.

Poets may be called upon to play a role akin to the role that preachers play. We may called upon to say something meaningful in a time of crisis. That’s not just a matter of doing an anti-Trump reading; that’s also a matter of doing something personal, even intimate. In one twelve-month period, I did six memorial services. Poets are called upon to address that void, that loss. People want you to help them make sense of great loss. I accept that role. I may not be able to help, but I’m going to try. That’s why, when Howard Zinn died, I wrote a poem for his memorial service. When my father died, I wrote a poem for his memorial service. And so on.

AF: I was very moved by the poem “Here I Am,” written in memoriam to your friend José “JoGo” Gouveia.

Espada: Joe was a pure soul. Joe was a working class Portuguese-American poet from Cape Cod. Joe loved poets, and Joe loved poetry. It was unabashed love, and he didn’t want anything in return for it. That’s what set him apart from many poets: he just wanted to be there, to be a part of it. Joe was an organizer by nature. He ran more than one poetry series on the Cape; he had a program on a radio station in Provincetown called “Poet’s Corner;” he had a regular poetry column for a paper in Hyannis called “The Meter Man. “ He was constantly engaged with poets and poetry.

The story I tell in the poem is based on something that happened at a conference in Boston in 2013, at a benefit for the organization Split This Rock. I was there to give a reading, and who should burst in the door at this party but JoGo. And jaws dropped. It really was like one of those scenes in a Western, where the door swings open and the piano stops tinkling, and everybody looks up and goes silent. This guy was was supposed to be hooked up to chemo—which he was—but the nurses unhooked him, and he left the hospital, climbed in his van and drove to Boston, all the way from the Cape. Nobody expected to see him there. He walked through those doors and he was grinning. He was wearing his Harley vest, with these wraparound shades, and he was a star. Of course, we crowded around him. It didn’t matter who else was there that night.

So Joe sat with me, and we talked. I really did say there what I say in the poem. Somebody asked me about Joe—“Who the hell is that man there?”—and I said, “That man there? That man is going to live forever.” I believed it. When somebody beats the odds over and over again, you really expect that person to keep doing it. Then, when the cancer came back at the end of the year, in November 2013, I wrote the poem “Here I Am” for Joe. It was, at first, just for him. I believe in elegies for the living. My approach to the elegy has changed. Now I believe in writing elegies for the living. Why not write the elegy while the guy is still here? If you know he’s going to go, write it while he can read it, and read it to others, as Joe did, from hospice. Write it while he can feel proud of it.

We were talking over the phone and Joe said, “I have a favor to ask you. My first collection of poems is coming out in April, and I want your poem to be the foreword. I said, “What? I’ve never heard of this.” He said, “Yeah, I want it to be the entire foreword for my book.” So it was. His book came out in April. Joe sent me a couple of copies and he signed one to me, with a long inscription. I sent him a copy back, with an inscription to him. Joe died in May. He stayed alive long enough to see his book come out. Don’t tell me that poetry makes nothing happen.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Martín Espada, Matt Hanson, Poetry