CD Reviews: Philip Glass Piano Works and Dessay’s Pictures of America

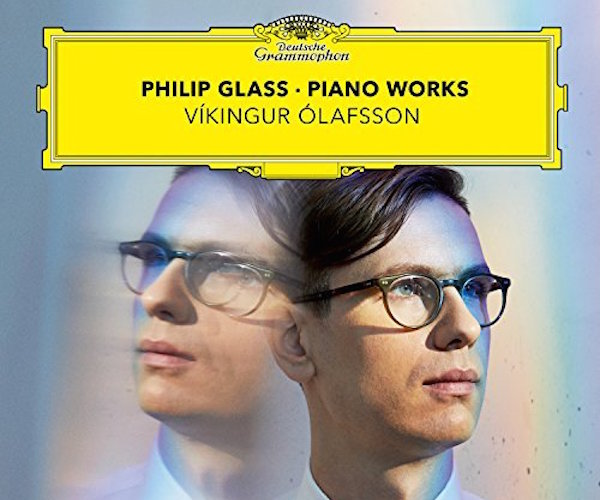

There have been lots of recordings of Philip Glass to hit the market recently. One of the highlights is Víkingur Ólafsson’s Piano Works.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

It’s hard to think of Philip Glass as a grand-old-man of American music. Yet he kind of is: eighty years old on January 31st, Glass and Steve Reich – both, incredibly, are octogenarians – are now the senior rank of American composers.

The good news in this is that there have been lots of recordings of Glass to hit the market recently. One of the highlights is Víkingur Ólafsson’s Piano Works, mainly a survey of half of Glass’s twenty Etudes (out of order), plus additional pieces, some reworked for piano and string quartet.

Glass wrote the Etudes over the course of about two decades, mainly as a means to improve his own keyboard technique. And, while they’re not on the same plane of vision or technique as, say, Liszt’s Transcendental Etudes or Debussy’s, there’s a lot to admire in the collection.

They certainly do more than endlessly repeat simple riffs. Yes, textural layering and varying levels of rhythmic dissonance are often their bread-and-butter, but look (or listen) more closely and you’ll find allusions to Chopin (in nos. 5 & 6), Prokofiev (nos. 13 & 14), even the mystical Beethoven of op. 111 (in no. 15). The Third Etude offers, if not the virtuosic demands of Liszt then at least some of his sense of propulsion. And there’s remarkable tenderness to be experienced, too, from the dusky Eighteenth Etude to the wistful and bittersweet no. 20.

Ólafsson really gets them all to sing. He understands this music to such a degree that even the most repetitious of the Etudes have direction and there’s a clear dramatic trajectory to each. Technical studies these pieces may be but, in his hands, they only sound like pure, purposeful music.

The Deutsche Grammophon disc’s opening and closing tracks rework the first movement of Glass’s 1982 classic, Glassworks, the second time through with strings (here the Siggi String Quartet, which also plays on an arrangement of the Second Etude mid-disc). It all works rather wonderfully: if, like me, you’ve had some difficulties with Glass’s aesthetic in the past, here’s a great place to reset your understanding of it. And, if you’ve always been a fan of his, well, you won’t be disappointed either.

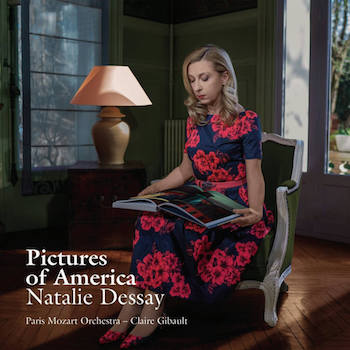

What does it mean to be American these days? Remarkably, that seems to be a rather confused question. So I suppose that the time is ripe for Pictures of America, a disc of songs from (mostly) mid-20th-century musicals sung in new arrangements by one of France’s finest coloratura sopranos accompanied by an orchestra named after Mozart.

OK, the performances, at least, aren’t as bad as the last sentence might suggest. For one, Natalie Dessay isn’t an unimpressive singer in this repertoire. Since leaving the opera stage in 2013, she’s reinvented herself as a chanteuse and her voice fits this style well: it remains marvelously light and agile, and her enunciation of text is excellent, if sometimes gently accented.

It’s a calculated risk of hers to take on this music, though. To her credit, Dessay approaches it on her own terms, not treating the songs as opera or lieder but as something else: soft, focused, and introspective vignettes or, well, pictures. If that means she doesn’t dent the impression made decades ago in some of this fare here by the likes of Ethel Merman, Judy Collins, and Frank Sinatra, well, that’s a price to be paid.

On the one hand, the Sony Classical album has a few high points. “I Feel Pretty” turns up, unexpectedly, in a quintuple meter (no doubt Leonard Bernstein, an asymmetrical meter enthusiast, would have enjoyed this). “I Keep Going Back to Joe’s & My Solitude” is suitably meditative and touching. “I’m a Fool to Want You” comes over as nice and sultry, as does “Autour De Minuit” (an adaptation of Thelonius Monk’s Round Midnight), which is Pictures’ sole French-language entry.

Unfortunately, “Autour” largely confirms one’s wish that this were an album of Edith Piaf standards rather than a disc of American songs. It doesn’t help that most of the arrangements are too somnolent and string-heavy. But there are also some downright odd interpretations on tap, too. “Something’s Coming,” half whispered, gently jazzy, lacks any semblance of intensity. So, astoundingly, does “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” The accompaniment to “Send in the Clowns,” so spare and concentrated in A Little Night Music, is in this setting far too busy for its own good. And so on.

As for programming, well that, too, leaves a bit to be desired. As lovely, for instance, as Dessay’s singing is in “A Place That You Want to Call Home” and “Two Lonely People,” they come on top of too many songs that sound the same: simply put, there isn’t enough variety of style, tempo, and character on offer here.

Claire Gibault and the Paris Mozart Orchestra play sweetly and well; sometimes, too, with a bit of verve. But there’s so little to get excited about in these arrangements, period, that one would be hard-pressed to find much to cheer about. Then again, given the sad state of American self-identity in the Age of Trump, maybe that’s just right: dreary, soupy settings of songs from the “Good Old Days,” compiled in a way that saps the vitality of the American spirit – or whatever’s left of it – once and for all.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Deutsche Grammophon, Natalie Dessay, Philip Glass, Piano Works, Pictures of America, Sony Classical