Visual Arts Review: A Luminous “Lumia” at Yale University Art Gallery

The result is reminiscent of a Mark Rothko painting — if it was projected through the refracted light of a prism.

Lumia: Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT, through July 23.

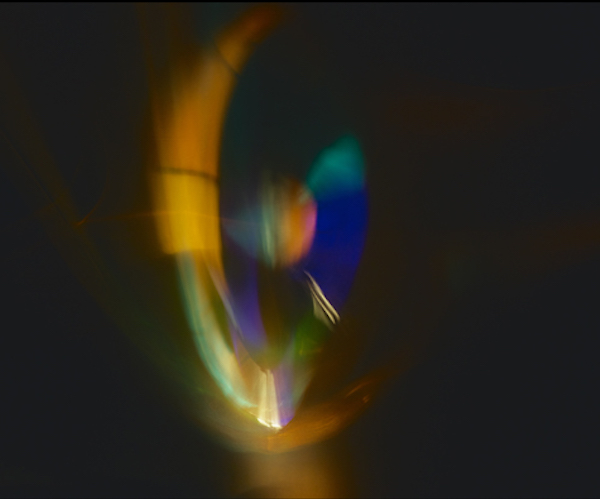

Thomas Wilfred, Lumia Suite, Op. 158, 1963–64. Projectors, reflector unit, and projection screen.

By Mary Paula Hunter

Lumia is a fascinating exhibit devoted to the groundbreaking work of the little known “light” artist Thomas Wilfred. It is a dazzlingly entertaining show on a number of levels. Devotees of the history of technology will be interested in a detailed explanation of the Clavilux, a machine that Wilfred invented in the early years of the twentieth century — its purpose was to transform and project light. Those interested in the interplay of color and rhythm will be charmed by Lumia in action — Wilfred’s term for Light Art — in which colors are put into performance, swirling, fading, and morphing. Finally, those interested in the intersection of visual art and philosophy, such as film director Terrence Malick (who included Wilfred’s work in his ground-breaking film The Tree of Life) will find much to ponder in Wilfred’s art.

Wilfred dreamed big when he invented his Clavilux, a “light” organ that he hoped would be practicable as well as affordable enough to be available in homes and movie theaters. Repair issues proved to be the machine’s undoing, but not before audiences and the art world were smitten with a contraption that seemed to reinvent art. The exhibit does the vision of a pioneering technological artist a great service by explaining, in considerable detail, the workings of the pre-digital Clavilux. The machine worked like a contemporary light board — adjustable keys were used to project (and control the strength of) beams of light through moving colored lenses.

Wilfred enjoyed considerable international recognition between the early 1920s and the mid ’60s. In 1963, MOMA’s director Alfred Barr installed what many critics consider to be Wilfred’s masterpiece — “Lumia Suite” — in the lobby of the museum. It was argued the artist had actually created a new art form: works such as Opus 160 or Opus 153 (“Spacetime Study”) brought a new kind of visual music to the canvas, an early manifestation of our interest in art that changes through time. “Visual Counterpoint, Op. 140” is a representative example of Wilfred’s work: vertical and horizontal lines of color intersect and dissolve in a continuous dance. The result is reminiscent of a Mark Rothko painting — if it was projected through the refracted light of a prism. “Visual Counterpoint” still astonishes.

Before devoting himself to promoting the manipulation of light as an art form, Wilfred supported himself as a lute performer, touring throughout Europe at the beginning of the century. Whether music served as springboard for Lumia is not entirely clear, but the hypnotic rhythmic intensity of his colors-in-motion makes appreciating Wilfred’s work a complex, at times baffling, experience. The artist’s obsession with the cosmos and infinity are evident in each work, yet each “canvas” stands alone, as if each piece was positing another world. On his deathbed, proto-Impressionist painter J.M.W. Turner whispered that “the sun is God.” Perhaps inspired by that romantic idea, Wilfred came up with different suns. “there’s a hell of a good universe next door; let’s go,” wrote poet E.E. Cummings. Wilfred seems to have taken him up on the dare.

Mary Paula Hunter lives in Providence, RI. She’s the 2014 Pell Award Winner for service to the Arts in RI. She is a choreographer and a writer who creates and performs her own text-based movement pieces.

Tagged: Clavilux, Lumia, Mary Paula Hunter, Thomas Wilfred, Thomas Wilfred and the Art of Light