The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 23

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

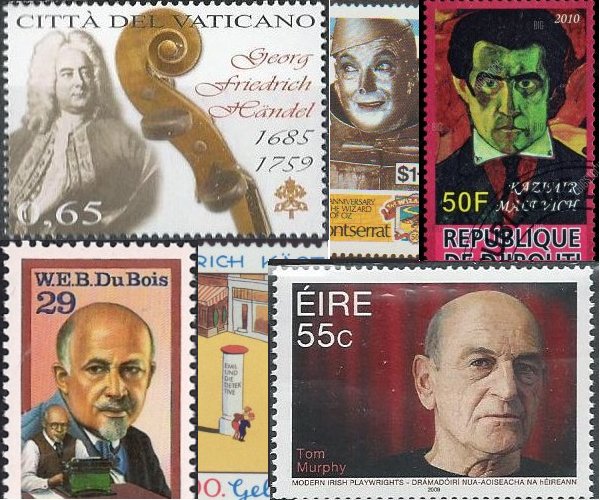

It’s Handel’s birthday today, as well as that of W. E. B. Du Bois, Kazimir Malevich, Victor Fleming, and Irish dramatist Tom Murphy, a great favorite of Arts Fuse contributor Steve Elman. We also salute artist Franz Stuck and writers Emil Kästner and Jef Geeraerts.

When Old Style/New Style date conflicts arise, I usually go with New Style, but Handel’s birthday, like that of Bach, is traditionally celebrated on the Old Style date. (The New Style equivalent is March 5. Handel died, by the way, on 14 April 1759 according to both calendars, Britain having adopted the Gregorian calendar just seven years earlier). Here are several choice items from my George Frideric Handel stamp collection, including some nice quite recent issues from Vatican City, Ireland, and Macedonia (where Handel is paired with Haydn, as in “Handel and Haydn”).

William Edward Burghardt “W. E. B.” Du Bois (February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was not only a giant among American sociologists and historians, he also wrote, as a small portion of his prolific output, several novels, including a novel trilogy called The Black Flame (1957-61). A native of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois was the first African-American to earn a doctorate from Harvard. (He had also studied at the University of Berlin.) A co-founder of the NAACP in 1909, he taught at Atlanta University, where his purview included not only history and sociology but also economics.

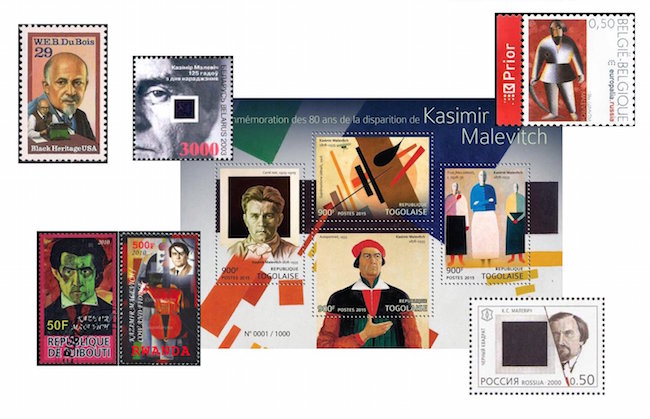

I was frankly surprised to discover so many stamps, from several countries, honoring Russian artist Kazimir Malevich (1878 – May 15, 1935), notably a beautiful souvenir sheet from Togo, issued just two years ago, which serves as the centerpiece of today’s second collage. The other Malevich stamps come from Belarus (inventively highlighting Black Square, 1915), Belgium (The Reaper on red, 1913), Djibouti (Self-portrait, 1912), Russia (Black Square again), and Rwanda (Cow and Fiddle, 1913, though I suspect this last is an all-too-common “illegal” issue put out by a non-governmental or not internationally recognized entity). But back to our hero: Kazimierz Malewicz (kah-ZEE-m’yesh ma-LAY-vitch) was born in Kiev to Polish parents and always signed his work using the Polish spelling of his name. He lived in Kursk and was already 26 when he went to Moscow to study art. Drawn to the avant-garde, he was calling his style “Cubo-Futuristic” in 1912, but went on shortly thereafter to found what he called Suprematism. The term was meant to express the “supremacy of pure feeling in creative art” over “visual phenomena of the objective world” (Malevich’s own words in his manifesto, From Cubism to Suprematism of 1915). Black Square is a quintessentially Suprematist statement and a pure example of geometric abstract art. Despite his philosophical repudiation of Socialist Realism, Malevich was not persecuted by the Soviet government until after the advent of Stalin, when much of his work was confiscated and he was banned from creating more. But he remained personally unmolested right up to his death in 1935.

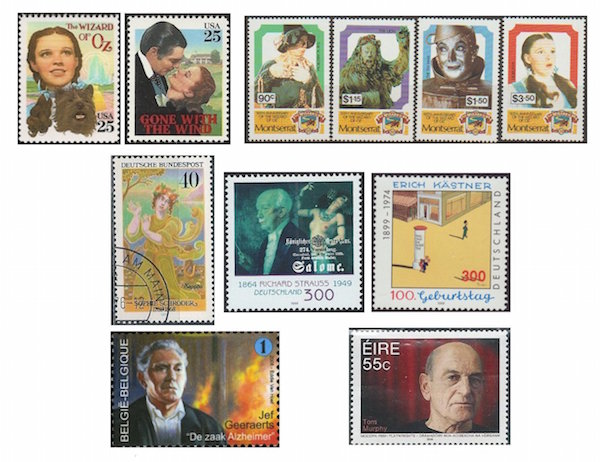

The director of The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind (both 1939), Victor Fleming (1889 – January 6, 1949), has no stamp per se, but we can salute him with US stamps issued to commemorate both of those movies and a set of four Wizard of Oz stamps from Montserrat. He was a photographer in World War I and for Woodrow Wilson at Versailles, worked as a cinematographer with D.W. Griffith, and started directing his own films in 1919. He won the Best Director Oscar for Gone with the Wind.

The German actress Sophie Schröder (née Bürger, 1781 – February 25, 1868) may have been born on the 23rd, but other sources give February 28 or March 1. The daughter of an actor, she first trod the boards as an opera singer in St Petersburg in 1793, going on to appear in Vienna, Breslau, and Hamburg. She excelled at tragic roles such as Lady Macbeth and Phèdre. From 1831 Schröder was engaged at the Munich Hoftheater, retired from the stage in 1840, and spent her remaining years in that city. Thrice married, she was the mother by her second husband of the soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, (1804–1860).

Our next two subjects were also Germans, artist Franz Stuck (1863 – August 30, 1928) and writer Erich Kästner (1899 – 29 July 1974). Born near the lovely town of Passau on the Danube, Stuck lived most of his life in Munich, beginning as an illustrator and showing his first paintings in 1889. He also worked as a sculptor and designer (his furniture won a gold medal at the 1900 Paris World Exposition) and was ennobled (as Franz Ritter von Stuck) in 1905. His style was modeled on and strongly reminiscent of Arnold Böcklin. Von Stuck’s students at the Munich Academy included Klee and Kandinsky. The only work by him that I can recall seeing on a stamp is his Salome of 1906, a detail from which appears on a stamp remembering the composer Richard Strauss, whose opera on the subject had its première a year earlier.

Kästner came from Dresden. He served with an artillery company in World War I and developed a marked distaste for militarism. He continued his education after the war, earning a living as a journalist, and began publishing volumes of his poetry in 1928. The same year saw the production of his best known work, the children’s book Emil and the Detectives, which has been made into films five times, the first in 1931 (Benjamin Britten loved it), and which by now has been translated into 59 languages. The stamp shows an illustration for it. Kästner went on to write more children’s books, satirical poems, and screenplays, but only one adult novel, Fabian (1932), an interesting experiment in that it attempts to mimic filmic techniques. Though looked on with sharp disfavor by the creatures of the Third Reich and questioned by the Gestapo, Kästner remained in Germany and was permitted to contribute to the screenplay for the famous wartime fantasy film Münchhausen (1943), albeit under a pseudonym. His Berlin home—along with many of his earlier writings—was destroyed in an Allied bombing in 1944, and Kästner was appalled when on visiting Dresden shortly after the firebombing he was unable to recognize anything of his home city. After the war he took residence in Munich, worked as an editor as well as in literary cabaret and radio, wrote his autobiography, demonstrated against nukes and the Vietnam War, and received a number of honors. His 1949 book Lottie and Lisa was made into the 1961 movie The Parent Trap with Hayley Mills.

We leave Germany now for Belgium and Jozef Adriaan Anna Geeraerts (1930 – 11 May 2015), known as Jef Geeraerts, who turned to writing only in his thirties. His first published novel, I’m Just a Negro (1962), was the result of his experiences as a colonial administrator in the Belgian Congo, where he had been severely wounded in fighting between two hostile tribes just prior to independence. He followed that book with more political novels, an erotic tetralogy (which was seen by some as not only pornographic but racist), and then the long series of detective novels for which he is best known.

If you want to know more about the work of Irish playwright Tom Murphy (born 23 February 1935), just ask Arts Fuse contributor Steve Elman, who’ll give you an earful. (He also got the Tom Murphy stamp for me during a trip to Ireland some years back.) A child of Galway, Murphy started his professional life teaching metalworking and practically “backed into” writing plays when his friend suggested it off-handedly. The second one he wrote, A Whistle in the Dark (1961), was performed in London and Dublin and raised some eyebrows, as did his anti-clerical 1975 play The Sanctuary Lamp. Sensitive to the criticism, Murphy worked as a farmer for some years. Later works include The Gigli Concert (1983), Bailegangaire (1985), and Conversations on a Homecoming (also 1985), and he has also written a novel, The Seduction of Morality (1994).

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse