The Arts on the Stamps of the World — February 16

An Arts Fuse regular feature: the arts on stamps of the world.

By Doug Briscoe

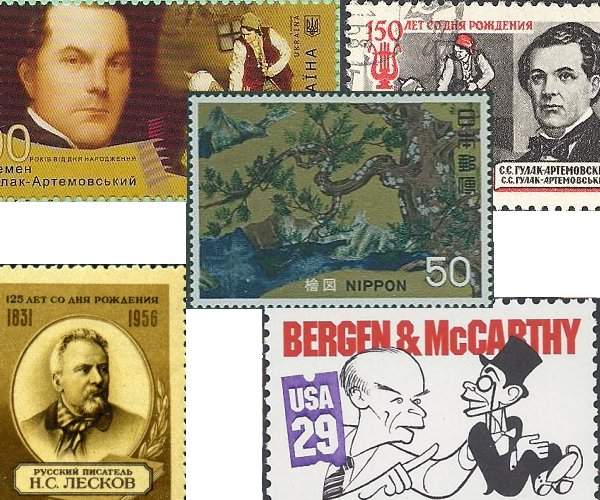

For February 16 I find only four creative artists on stamp of the world: 16th-century Japanese painter Kanō Eitoku, two 19th-century Slavs, Ukrainian composer and baritone Semyon Gulak-Artemovsky and Russian novelist Nikolai Leskov (the author of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, for you Shostakovich fans), and American ventriloquist Edgar Bergen.

Kanō Eitoku (1543 – October 12, 1590) lived at the time of the powerful warlords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi and provided paintings for both. The son and grandson of prominent painters, Eitoku had gifts that were acknowledged from an early age and grew to such eminence as to establish his own school. Modifying the Chinese-derived style of his grandfather, Kanō Motonobu (1476–1559), Eitoku created the “monumental style” (taiga), described by Wikipedia as “characterized by bold, rapid brushwork, an emphasis on foreground, and motifs that are large relative to the pictorial space.” The stamp, from 1969, shows a detail from a sectioned panel, Cypress Trees, dated about 1590. Unfortunately, most of Eitoku’s work was lost during the violence-wracked Sengoku period (c. 1467 – c. 1603) in which he lived.

Semyon Stepanovych Gulak-Artemovsky (February 16 [O.S. February 4] 1813 – April 17 [O.S. April 5] 1873) took vocal training directly from Glinka beginning in 1838 and was admitted into the Imperial Chapel Choir. He studied further in France and Italy and performed in Florence (he was one of the few Russian opera singers of his day to be comfortable in other languages), and on his return to Russia created the role of Ruslan in Glinka’s beloved opera (1842). He was a soloist at the Imperial Opera for some 22 years, thereafter singing for a season or two with the Bolshoi Theatre in Moscow. As a composer he is best known for his comic opera A Zaporozhian Cossack Beyond the Danube (1863), for which he wrote his own libretto and sang in the première. Gulak-Artemovsky’s stamps were issued by the Soviet Union in 1963 and by Ukraine for his centenary four years ago.

Nikolai Semyonovich Leskov (16 February [O.S. 4 February] 1831 — 5 March [O.S. 21 February] 1895) was an important Russian writer, highly regarded by such figures as Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Gorky. His beginnings, however, were not promising, despite his birth to a well-educated criminal investigator and the daughter of a Moscow nobleman. His father lost his position after some squabble, and the family’s circumstances were reduced, then Leskov did poorly in school, taking five years to earn a two-year graduation certificate. Following in his father’s footsteps, he took to the law but after a time went to work for his aunt’s English husband in business. His reports to his superior so struck that gentleman that they were deemed worthy of publication. Leskov wrote as a journalist on social issues, contributing to newspapers in Odessa, Saint Petersburg, and Kiev, as well on economics. He began writing fiction in 1862 with the short story “The Extinguished Flame”. (In the same year he had been in Paris, where he translated a work by Božena Němcová, whose stamp we saw here on the 4th inst.) His novel Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District was written at Kiev in 1864 and published in Dostoyevsky’s Epoch magazine in January 1865. (In 1930, the story was made into an opera by Shostakovich, which brought the wrath of Stalin down on his head. After the dictator’s death, Shotakovich revised the score as Katerina Ismailova [1956].) Leskov’s early efforts were largely ignored by critics but came in time to be regarded as masterpieces, garnering particular praise for his depictions of strong female characters. Leskov was rather a feisty fellow, both in his writing and in his personality. He was fired from a periodical for his articles on police corruption and from the Ministry of Education for his essay lampooning church functionaries, and he was estranged from his two children. One critic wrote of him that he “had few friends in literary circles but a great many readers all over Russia.” (The Education Minister offered Leskov the option of submitting an application for retirement, but Leskov said no, and when the minister asked why Leskov was being so stubborn, the reply came, “For a decent obituary.” By his own direction, his funeral was held in silence, all speechifying forbidden.)

Edgar Bergen (1903 – September 30, 1978) was born to Swedish immigrants named Berggren in Chicago, though he spent his earliest years on a farm in Michigan and in Sweden, where he learned the language. Self-taught in ventriloquism, he was only sixteen when, back in Chicago, he hired a woodcarver to make the dummy—modeled on a “rascally red-headed Irish newspaperboy” from the neighborhood—that, even then—1919—was dubbed “Charlie McCarthy.” Soon he was performing professionally and altered the spelling of his name for the orthographically challenged. Bergen and McCarthy had roles in a number of films, including You Can’t Cheat an Honest Man (1938) with W. C. Fields. A curiosity about Bergen was his huge success on radio, where, of course, his ventriloquism skills were invisible. He was a regular on The Chase and Sanborn Hour for twenty years while also starring on his own program from 1949. On his own, he played Grandpa Walton in the original Waltons movie, The Homecoming: A Christmas Story (1971) and could often be heard in old radio routines on the succeeeding TV series. He is also the father of actress Candice Bergen. Brush With Greatness Dept.: I caught a glimpse of him once at a Los Angeles party I attended as a teenager with my jet-setter sister. He died about four years later. Regular readers of this page (if there is such a thing) may recognize his stamp as coming from the same Al Hirschfeld-drawn set as the one showing Jack Benny that we saw here just two days ago.

I find it shocking that the United States has never honored Henry Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) on a stamp.

A graduate of the University of Massachusetts with a B.A. in English, Doug Briscoe worked in Boston classical music radio, at WCRB, WGBH, and WBUR, for about 25 years, beginning in 1977. He has the curious distinction of having succeeded Robert J. Lurtsema twice, first as host of WGBH’s weekday morning classical music program in 1993, then as host of the weekend program when Robert J.’s health failed in 2000. Doug also wrote liner notes for several of the late Gunther Schuller’s GM Recordings releases as well as program notes for the Boston Classical Orchestra. For the past few years he’s been posting a Facebook “blog” of classical music on stamps of the world, which has now been expanded to encompass all the arts for The Arts Fuse