Book Review: “The Mary Julia Paintings of Joan Brown” — In a Pantheon All its Own

Poet William Benton’s slender and beautiful book can safely be described as sui generis.

The Mary Julia Paintings of Joan Brown by William Benton. Pressed Wafer, 40 pages, $17.50.

By Timothy Francis Barry

There’s a memorable phrase in the Aeneid, sanguinus sacri, which translates as “the blood of victims sacrificed to the gods.” That notion of an expiatory rite permeates this slender and beautiful new book, which can be safely described as sui generis.

Not exactly a memoir, not quite an elegy, unequal parts confessional and digressional personal essay, novelist and poet William Benton has created a kind of ceremonial text that cuts to the heart of his challenging relationship with his ex-wife while also offering a tribute to the painter Joan Brown (seventeen of her works are reproduced). To which strange gods he is sending his offering is left unsaid — the enigma only sharpens the pull of his images.

All too often the intersection of beauty and sadness degenerates into a maudlin cliche. Benton weaves a brusque tale that, on the surface, gives us the standard downs and outs of a troubled marriage. But he manages to fold in lyrical glimpses of hope and chances for survival, only to come back around to real life — where chaos is inevitable.

Joan Brown was a figurative painter from the San Francisco Bay school of the 1960s, known for her use of thick, meaty impasto and a wiggy humor she spread on with expressionist bravado. William Benton has been a traveller on what he calls the “American circuit of misfits and failures”: a jazz musician, writer, and professor. The two seekers collided in the bicentennial summer of 1976, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, where Benton had by some combination of alchemy and self-promotion landed a job as an art gallery director.

He contacted Brown, who agreed to a show of her new paintings. Benton was in the throes of an off-again/on-again extended break-up/breakdown of his decade-long marriage to Elaine, a woman who, as the fates would have it, was a dead ringer for the subject in Brown’s ‘Mary Julia’ series, which Benton ended up exhibiting in the gallery.

Benton’s descriptions of the marital dance amount to a kind of prose poetry:

In the ongoing months, the changes in our lives were settled into, with a sense of defenselessness. Sex and the lilt of intimacy lacked permission. Moments of happiness were guarded at best. I was too young and too self-involved to believe that we couldn’t recover from this….The pursuit of places in the sun–with the hope of rescuing our marriage–was, on another level, purely a flight from pain.

Tragic figures come in threes in this narrative, a fairy tale conceit, yes, but with plenty of realistic kick. Elaine hems and haws, finally driving cross-country with the kids packed into the sedan, seeking yet another realignment with her husband: “the euphoric moment of reconciliation.” The self-involved poet seems to put the blame for the domestic breakdown on the wife: “she was unhappy in ways elusive to us both.” Maybe yes, maybe no–these loose ends and dangling possibilities are the lifeblood of this book. No answers are offered.

This is a narrative about a woman who died. Actually, two women who died. But it is more about the fallout, the aftermaths, the embattled emotional leavings of intimacy gone wrong. It is about survivor’s guilt and the lack thereof. But then, Benton makes no apologies, no concessions. What is, just is.

The Joan Brown story is not told here in its entirety. She died in 1990 in a random accident that occurred while she was installing a tiled obelisk in India. What brought her there, the lives she touched along the way, her inspiring nature, her amazing paintings and sculptures, and how she impacted the American culture, is an odyssey that needs telling.

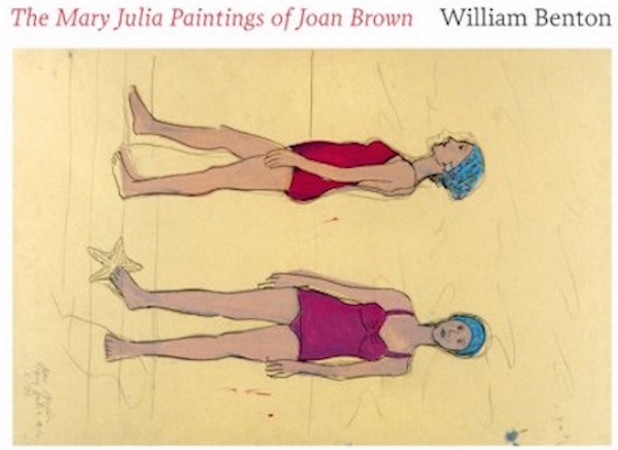

The 17 brightly colored paintings that are included in the book — the Mary Julia Series– offer few revelations into Brown’s life, though there are some psychological clues. The placement of Mary Julia’s arms is a sign: in one Matisse-inspired painting her arms are akimbo, in several others she has her hands behind her head in a defensive yet intriguingly sexual pose that seems to say “come take me, if you need to.” In yet another ambiguous configuration of hands, she covers her chest, seemingly out of self-protection.

The meaning of these images are elusive and disturbing; they serve as provocative counterpoints to Benton’s words. Seen as a work of art history, the volume offers an oblique window into Joan Brown’s world, which is more complex than it at first appears. Taken as a memoir, it is a powerful document of loss and lamentation. Every page is stained with the blood of the poet, which elevates this extended essay into a pantheon all its own.

Timothy Francis Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, both in Provincetown.

Tagged: Joan Brown, Pressed Wafer, The Mary Julia Paintings of Joan Brown, Timothy Francis Barry