Book Review: “Acting” on the American Silver Screen

Seven essayists in a new anthology take on a daunting task: characterizing styles of acting through the evolution of American film.

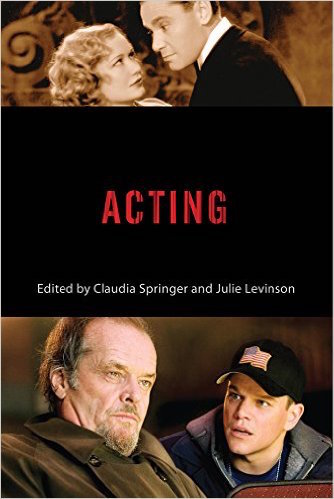

Acting, Edited by Claudia Springer, Julie Levinson Contributions by Victoria Duckett, Arthur Nolletti Jr., David Sterritt, Julie Levinson, Donna Peberdy, Cynthia Baron. Rutgers University Press, 240 pages, $26.95 (paperback).

By Gerald Peary

Forty years and more as a film critic, I can say that the most daunting thing to go on about, it still eludes me, is the acting in a movie. How tough to be given the task of the seven essayists for the new anthology, Acting (Rutgers University Press), edited by two Massachusetts academics, Claudia Springer of Framingham State College and Julie Levinson of Babson College. Each was asked to characterize a vast era of American film history (1895-1927, 1928-1946, etc.) in terms of explaining the acting styles prevalent in that era. And why.

Is that even possible? The best essays, the most focused ones, settle on a couple of manageable issues about acting relevant to their assigned period and mostly stick with those. The least successful writers ramble, free associating anything and everything discovered about acting in their time frame. What they miss desperately is an overriding thesis.

Victoria Duckett gets things right with the opening essay, “The Silent Screen, 1895-1927.” As a start, she reiterates the point that university film professors make endlessly to their unconvinced students: that acting in the silent era is not woefully bad but just intrinsically different from what we are used to. Does a case need to be made for the excellence of Lillian Gish? Duckett describes in the minutest detail Gish’s seminal interpretation of the downtrodden Lucy in D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms. Says Duckett: “In the quick gesture of a finger, the fidgeting clasp of a hand around her shawl, the brush of a mother’s letter against a face, and so on, we see Lucy’s character emerge.” But Duckett also finds deft acting where even champions of silent cinema might only see campiness; for instance, the 19th century diva, Sarah Bernhardt, 67, giving an adieu performance for the camera in 1911. She’s a creaky 16-year-old Camille in La Dame aux camellias, which she’d played eternally on the stage.

“The idea that Bernhardt theatrically overacted…or too obviously ‘performed’ on screen, “says Duckett, “misses the nuances of her movements in Camille.” An assumption we make is that stage performers plucked for early cinema simply repeated rote what they did before a live audience. In an impressive display of research, Duckett demonstrates that such isn’t true at all for Bernhardt, who, for good or bad, transformed her acting for the cinema. Duckett quotes a most reputable source who hawkishly studied Bernhardt’s portrayal of Camille in the theater. Poet and dramatist, William Butler Yeats. Yeats counted 27 occasions when Bernhardt self-consciously held a pose for the audience to contemplate, sometimes for many seconds. In utter contrast, Bernhardt moves rapidly throughout the movie version. There are no tableaux at all.

Duckett notes that acting in the silent era is different from later epochs because, sans sound, the director could speak up, coaching his actors in real time as filming proceeded. That’s what Griffith regularly did with his actors, orchestrating gestures and facial expressions, including with Lillian Gish. And Bernhardt’s consumptive Camille? Perhaps it was her film director who was frustrated by the studied stage business, urging her on: “Faster, Sarah, faster!”

Poor Arthur Nolletti, Jr., author of acclaimed books on Japanese cinema, here given the absurd, unthinkable job of pinning down Hollywood acting from 1928, the dawn of sound, through 1946, the post-War period of film noir. It can’t be done. Kudos to Nolletti for trying, sliding from The Star System to The Production Code to in-depth descriptions of the acting in four films from four genres. Unfortunately, the former is too generalized, the latter too specific to illuminate the years under discussion. Perhaps the editors of Acting should have suggested to Nolletti that he restrict his essay to just The Star System? Or, better, that he’d concentrate on how acting styles were dictated by the genre choices of the various studios: the snappy, street-slang talk for Warner Brothers’ blue-collar urban dramas, the expressionist acting for the horror films of Universal, etc.

The ordeal is not much easier for David Sterritt, charged to make sense of 1947-1967. Simply, 1947 has nothing in common with 1967, when the studio system had broken. The least effective part of his essay is his summations of the careers of half-a-dozen actors and actresses, from Montgomery Clift to Marilyn Monroe. I didn’t get the point of it. But Sterritt is great explaining the history of The Method, how Stanislavsky and Strasberg came to Hollywood, and how it all impacted on internalized post-War film acting. Sterritt also acknowledges what becomes clearer every year about movies of the late 1940s and 1950s. Many famous Method-influenced performances, from formidable actors such as Marlon Brando, Rod Steiger, Lee J. Cobb, now seem far from authentic and truthful. They are, instead, hammy, over-the-top.

Sterritt is very funny bringing down the revered James Dean, demonstrating that Dean used the same shtick, “the many shared tics and traits,” in both East of Eden and Rebel Without a Cause. Did Dean betray the Method with a set of calculated, show-off mannerisms? Said East of Eden filmmaker, Elia Kazan, watching the young actor’s final performance in Giant: “He looked like what he was: a beginner.”

Julie Levinson, author of the superb book, The American Success Myth on Film, has the least years to cover for “The Auteur Renaissance, 1968-1980”. That certainly aids in her offering the most coherent chapter of the book. Levinson concentrates on the post-Method acting in films made by the bold individualistic filmmakers of the 1970s—Coppola, Scorsese, Altman, Bogdanovich—and makes fine sense of what is seen on screen. If only every essay in the book was this clear:

Although all these factors—the ascension of youth culture, the relaxation of prohibitions against sex and violence in the movies, the validation of ethnicity and ordinariness in the name of truthfulness—had a part in shaping film performances in the late 1960s and 1970s, arguably the most significant cultural influence on actors’ conceptualization of and preparation for their roles was the self-actualization movements that proliferated during the years in question. The cultural imperative [was] to explore and develop the self.

EST and Esalen and self-help books everywhere—and, alongside, exploratory movies. Levinson continues: “…the creation of characters who evinced emotional truth was, increasingly, the measure of a good performance.”

I would add to what Levinson asserts. What happens in 1970s New Hollywood, with Jack Nicholson and Warren Beatty as thespian kings, is the demise of the traditional hierarchical relation of director and actor. Post-1960s, they are big-headed equals. They are off-screen male buddies, drinking, doing drugs, cavorting. The performances are in every way collaborative, with indulgent actor and director as joint “auteur.”

I’m in agreement with Donna Perbody that the 1980s are not quite the cultural wasteland in filmmaking that the era is thought to be. But I’m perplexed understanding why she chooses to see this time period through the lens of “three modes of acting—transformation, excess, the ensemble.” Transformation and excess are parallels, but ensemble? A “mode of acting?” I don’t think so. Yes, the Brat Pack is an ensemble but there are ensembles in every era. Think the wide-ranging career of director Howard Hawks. What’s different about ensembles in the 1980s? There is no explanation. Even discussing transformation, Perbody fails to contextualize. Why is she not writing at length about the coming out of gays and lesbians in that period, and also the zeitgeist of gender-bending and gender fluidity?

James Dean in “Giant.” As an actor, still a beginner.

The final chapter, Cynthia Barron’s “The Modern Entertainment Marketplace 2000-Present” is a dry but reasoned rumination about, among other things in our CGI epoch, the “acting” of animated characters and the of-screen contribution of well-known Hollywood personalities who provide the voices. Yet I would have preferred a vastly different essay about performance in the New Millennium. The essay would deal with acting in American independent films, starting with the raggedy improvisations of “Mumble Core” movies.

And what about the influence on the acting in independent-minded American movies by today’s European arthouse cinema? Post-2000, the European film typically opens in the middle of an action and there is never an explanation of who the characters are or were. Unlike Method-influenced films, there’s no backstory for actors to lean on for characterization. It’s very existential: the “essence” of characters begins when the cameras roll. It’s all in the frame. Characters vanish when the cameras stop, like Antonioni’s photographer ejected from the shot at the end of Blow-Up.

That’s what I’d love covered in Acting, this enthralling trend in current cinema so deeply anti-Stanislavky: how do you act when there’s no interior? When you are someone like France’s Isabelle Huppert who requires no discussions with her director during the filming and who discovers her character each day as she shoots?

Gerald Peary is a retired film studies professor at Suffolk University, Boston, curator of the Boston University Cinematheque, and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema, writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: the Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty, and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess.

Tagged: Acting, American Film, Arthur Nolletti Jr., Claudia Springer, Cynthia Baron., David Sterritt, Donna Peberdy, Julie Levinson, Movies, Rutgers University Press