Book Review: “Dharma Lion” — The Rich Heritage of Allen Ginsberg

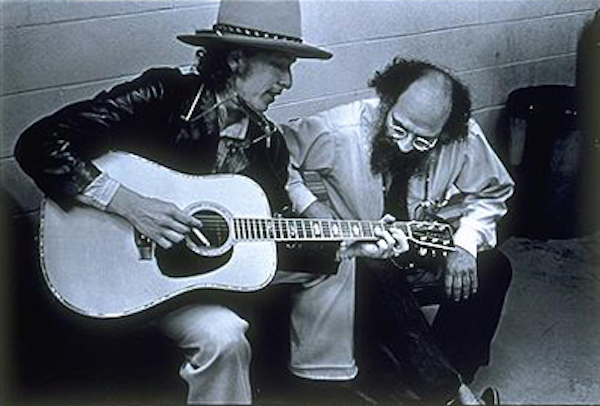

Recently, the power of Allen Ginsberg’s legacy could be felt in the controversy over the decision to award Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature.

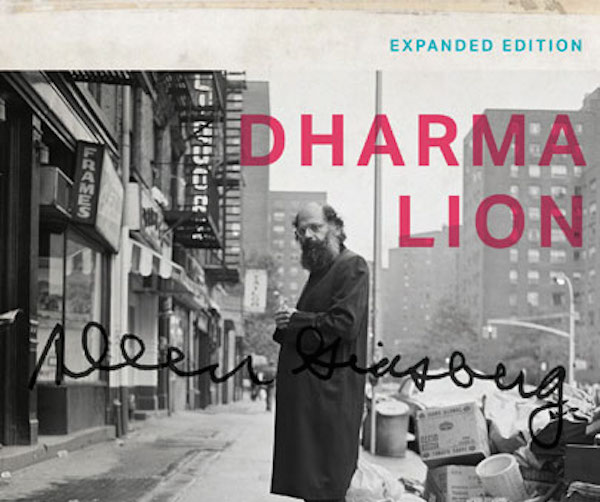

Dharma Lion: A Biography of Allen Ginsberg (Expanded Edition), by Michael Schumacher. University of Minnesota Press, 793 pp., $24.95.

By Troy Pozirekides

It’s tempting to think of Allen Ginsberg and his Beat cohort, perennially reborn in cinematic depictions by the latest generation of twentysomethings, as forever young. It makes their achievement seem only suitable for less-than-serious youth. The sheer size of Michael Schumacher’s expanded edition of his Ginsberg biography Dharma Lion – nearly 800 pages including endnotes, bibliography, and index, covering the poet’s seven decades, his family and peers, the development, expression, and evolution of his political attitudes and art – answers this charge quite nicely. Schumacher’s style, sensory and engrossing, invites the reader to drop in on key moments in the poet’s life while it never strays too long from the vast historical sweep of the biographical enterprise. His life of Ginsberg is a broad landscape replete with idiosyncratic detail (rooted in a complete study of the Ginsberg archives, as well as interview transcripts) that demands close examination and, largely, holds up to such scrutiny.

Irwin Allen Ginsberg was born in in Newark, New Jersey in 1926 but raised in Paterson, the son of Louis, a schoolteacher and poet of local renown, and Naomi, who was “fiercely political, with Communist roots dating back to her girlhood in Russia.” His parents’ attitudes and preoccupations became his own, as Schumacher writes, early on:

Poetry and unconventional politics — passions for which Allen Ginsberg would become widely known — passed from parents to son like steely faiths, already forged, awaiting proper test.

Those faiths would be put to such a test at Columbia University, where Allen matriculated in hopes of pursuing a career in law in order to help the “working oppressed.”

Early confidence about his chosen profession, as well as the stated program of his early poetry (“the concomitant potential of all art is communication”), were challenged when he met Lucien Carr, a sophisticated and intelligent student two years his senior, who impressed Ginsberg greatly, noting the “daemonic fury that seemed to dwell in his mind.” The two were active participants in informal, salon-style discussions on art and literature that soon swelled to include Jack Kerouac and William S. Burroughs. Carr was the first in a line of “challenging forces” that would provide Ginsberg with the constant nudges (and, occasionally, about-faces) he needed to grow as a person and artist.

Much like Ginsberg’s other major influences, Jack Kerouac and Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Carr proved to be a magnet for controversy, most notably because of his 1944 killing of David Kammerer, a former high school teacher of Carr’s who, obsessed with the young man, had been stalking him around the country for years. Carr pleaded guilty to first-degree manslaughter, claiming he had acted in self-defense, and got off after spending some time in a psychiatric hospital. But the episode had a harrowing, as well as a unifying, influence on the burgeoning intellectual circle centered in and around Columbia. The event showed the young artists, at first hand, the fragility of life, the omnipresence of mortality. To Ginsberg, it seemed that art needed to reckon with the ever-present threat of immediate destruction; his intimation of disaster was confirmed shortly thereafter by the detonations of the first atomic bombs at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, just as he was coming of age as a man and an artist.

Ruination was all too easy to glimpse in Ginsberg’s home life too, where his mother Naomi’s mental illness proved to be a constant struggle. She was institutionalized at length for much of Ginsberg’s childhood, and when she was home she would frequently issue schizophrenic tirades on the conspiracies she perceived to be set against her, accusing the government and her mother-in-law of spying on her thoughts. Ginsberg’s sympathy for her, as well as his role as her unofficial caretaker, were complicated by her tendency to walk around their home naked, which would have a lasting, disturbing impact on his relationship with sexuality throughout his life. With Naomi indefinitely institutionalized after her and Louis’ marriage crumbled, Ginsberg was asked to sign off on her lobotomy in 1948. He was only 21 years old.

These early experiences of madness, hysteria, and annihilation would weigh on Ginsberg for his entire life. Over the ensuing decade, they would drive his art’s aspiration. A series of hallucinatory visions he witnessed over the rooftops of East Harlem in 1948, as well as experimentation with nitrous oxide, marijuana, and Benzedrine, inspired his poetic vision, though his writing from this time remained no more than stilted attempts at traditional lyric. After being arrested as an accessory to robbery the next year, he was admitted to the Columbia Presbyterian Psychiatric Institute, where he began journaling in “succinct objective notation,” a marked alternative to the ornate, stylized verse he had been writing up to that point. These journal entries were later mined and used as the basis for his poetry collection Empty Mirror, which fit Ginsberg’s latest definition of poetry as a “clear statement of fact about misery.”

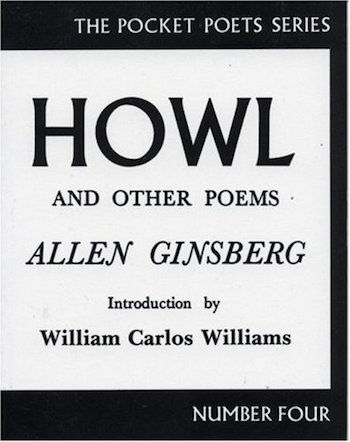

Upon being discharged from the Psychiatric Institute and finishing his degree at Columbia, Allen left New York, not to return for several years. He found his way to Berkeley, California, via Mexico and South America, where he settled in a one-room garden cottage near the University of California campus. It was here, in between trips to San Francisco to convene with the local intelligentsia, that he wrote the long, frenetic lyric that became “Howl,” the poem that catapulted the young poet into the public eye. At once a lament for the “best minds of my generation destroyed by madness” and a paean to the “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night,” “Howl” was matched in its literary impact by the sheer power of the public readings Ginsberg gave throughout the fifties and sixties, first at small galleries and coffee shops in the Bay Area and then onto packed college auditoriums, arenas, and even London’s Royal Albert Hall.

The poem was a literary event when published in 1956, to be sure, just as Eliot’s The Waste Land had been for the previous generation. “Howl,” however, rocketed well beyond the printed page thanks to these explosive performances, which Schumacher credits with beginning “a surge of poetry readings that brought poets into contact with their audiences and reestablished poetry as an oral form.” The poem’s triumph over the charges in a high-profile obscenity trial brought it national attention and readership, underscoring its ability to stimulate and agitate the country’s political consciousness.

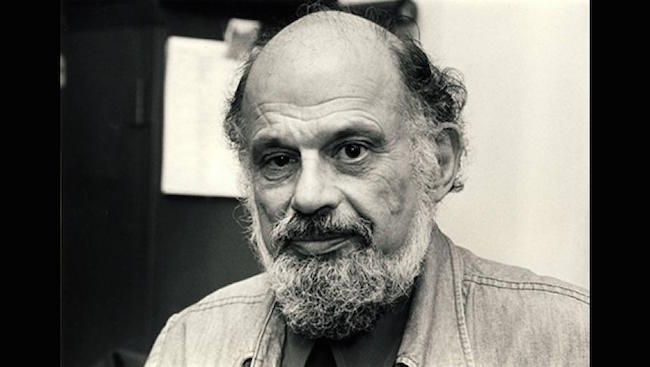

Poet Allen Ginsberg — he helped invent the modern literary world. Photo: Wiki Commons

Naomi Ginsberg died in 1958, not long after the publication of “Howl,” and Ginsberg felt compelled to express his anguish in verse. The resulting poem, “Kaddish,” named after the ancient Jewish prayer of mourning, was nearly universally praised by critics for its depiction of a family’s struggle with mental illness and as well as the poet’s grief at the death of his mother. In terms of literary style, the poem expanded on the oratory “Howl,” this time creating a subdued, rather than incendiary, effect. Ginsberg “broke many of the lines with dashes, so that thoughts (or long lines) would be broken by a series of ‘sobs’” likely uttered by the poet during composition of “fifty-eight pages, many marked by tears that fell onto the paper as he wrote.” In February 1959 Ginsberg read “Kaddish” before a crowd of fourteen hundred at Columbia University’s McMillin Theatre. His father, Louis Ginsberg, was in attendance for the performance, “which left both father and son in tears.”

Schumacher depicts many more experiences and achievements over the ensuing decades of Ginsberg’s life. There are far too many to summarize in a review. To highlight these relatively early successes — the composition and debut performances of “Howl” and “Kaddish” — is to underscore their significance as Ginsberg’s most influential works, both on others as well as on himself. They inspired him to depart from tradition and take his poetry directly to his followers through public reading and performances. These were not dispatches from the ivory tower or elite literary magazines. So contradictory was his work and presence that it could serve as grounds for his deportation by authorities in Cuba and Czechoslovakia and as a salve for the angry mobs at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago (a crowd, about to become violent, was quelled when Ginsberg led them in seven hours of meditation). Throughout the tempestuous political climate of the sixties and seventies, Ginsberg admirably demanded that words inspire responsible action, action that reflected a collective voice. He attempted to use his fame as a poet to steer the establishment toward nobler ends.

Schumacher’s biography of Ginsberg is vast in its sweep but, understandably, not comprehensive. We hear from some of the key artistic figures in Ginsberg’s generation, thanks to quotations from interviews and correspondence. But several people close to Ginsberg on a personal level become, in effect, silent passengers along for the ride. What we are given of these people is limited, ultimately, to what they gave Ginsberg. When he is away from them, we are away from them – out of sight, out of mind. This disappearing act extends most notably to Peter Orlovsky, Ginsberg’s mercurial partner and lover from the mid fifties until the poet’s death in 1997. There are just two brief references to the couple’s correspondence in the book, and no substantial samples of Peter’s words. Peter, by all accounts a complex, troubled, and consequential force in Ginsberg’s life, is pushed to the margins. Schumacher’s estimation of him is revealing: “Peter was both a vital person in Allen’s life and another cog in the Ginsberg cottage industry.”

Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg. Photo: Elsa Dorfman.

Troubling too is Dharma Lion‘s treatment of the women in Ginsberg’s life. Serious coverage is almost entirely limited to a single paragraph and a footnote that addresses a critical review. Schumacher accurately cites in that footnote “that the writers [of the Beat Generation] could not find a way to create realistic female characters who addressed the late 1950s sexism with the same earnest intent that those same writers took on other issues.” True, but that does not excuse portraying the women in their lives, Ginsberg’s included, with the same indifference. The one exception to this blind spot is Naomi Ginsberg, but even she figures more as an exemplar of Ginsberg’s relationship with mental illness than of his experiences with the opposite sex. When Schumacher attempts to explore this relationship as an example of the poet’s empathy for women in general, it’s one of the few moments where his usual polite, workmanlike approach to contextualizing Ginsberg’s poetry seriously falters. Arguing that “Kaddish” “detailed the experience of being a woman in modern society,” praising “its understanding of all things vital to the contemporary woman,” he then woefully reduces Naomi to “a heroic symbol, not of a generation but of an entire gender destroyed by madness.”

These shortcomings aside, the biographer does a fine job of highlighting Ginsberg’s assessment of the inheritance he and his generation were leaving behind:

“The real legacy of Kerouac and the Beats is one of literary liberation,” he told reporters, underscoring a point he had been making all along — that the Beats were, first and foremost, artists, not some kind of social fad.

Recently, the power of Ginsberg’s legacy can be sensed in the controversy over the decision to award Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature. There has been a lot of hand wringing over what that means for the state of literature, poetry, and poetics in our time. The adverse responses were varied in their diagnoses and prescriptions, but most shared a key deficiency: too limited a definition of poetry and too narrow a judgment of its scope. The literati’s debate over Dylan, and what his ‘official’ designation as a modern poet means culturally, is sure to continue long after the spotlight of the Swedish Academy’s announcement has dimmed. But this is not an isolated event: it is the end result of a shift in public attitude toward poetry that Dylan, but also those who influenced him, like Allen Ginsberg, helped inspire.

This, I think, is what makes Dharma Lion the book best suited to answer the question that the critics of the Dylan decision are really asking: how did we get here? This is not to discount the work of Dylan, undeniably a complicated genius, but rather to understand how the table was in no small way set for him (as well as for all those who seek to write poetry in the modern era) by Allen Ginsberg — another, equally complicated, genius. As Michael McClure remembered, “in all our memories no one had been so outspoken in poetry before … we wanted to make it new and we wanted to invent it and the process of it as we went into it. We wanted voice and we wanted vision.” Ginsberg gave us both, and then some, and we are still very much living, whether we know it or not, in a world of his invention.

Troy Pozirekides is a freelance writer and critic.

As with most high level creative individuals, Allen Ginsberg was gifted at self-promotion as well as holding historical grudges whether justified or not. For nearly 60 years, Ginsberg’s version of the story of a lost manuscript that inspired Jack Kerouac wrongly blamed poet/artist Gerd Stern (now 88). Stern had been wrongly accused of tossing what Kerouac called “the greatest piece of writing I ever saw” over the side of a Sausalito houseboat.

The 16,000-word screed to Kerouac from his friend and literary muse Neal Cassady was found intact in a house in 2012 in Oakland.

Apparently, Cassady, who wrote the letter over three amphetamine-fueled days in 1950, sent it to Kerouac just before Christmas. After reading it, Kerouac said that he scrapped an early draft of On The Road and rewrote it in a similar stream-of-consciousness style. Of course, the result was a literary classic and a new style of prose called Beat literature.

According to Kerouac, if Stern hadn’t dropped the letter off that boat, Kerouac told the Paris Review in 1968, the writing would have transformed his car-stealing, marijuana-dealing, con-man friend Cassady into a literary giant.

Stern said that Beat poet and Kerouac friend Allen Ginsberg sent him the letter sometime in the 1950s, hoping he could get it published by Ace Books, for which Stern was then a literary agent.

“It was part of a stash of about two and a half feet of books and manuscripts that Allen had collected from all of his buddies,” Stern said, adding he sent them all back but one — William S. Burroughs’ novel “Junky,” which was eventually published.

“Soon thereafter Allen started the overboard rumor. What really happened was that Ginsberg sent the letter to Richard Emerson at Golden Goose Press, and Emerson didn’t bother to read it.

When Emerson folded Golden Goose Press, he gave his archives, including the still-unopened letter, to a business associate who took the material home.

There it stayed until Los Angeles performance artist Jean Spinosa was cleaning out her late father’s house two years ago. Question: Why did Ginsberg say Stern tossed the letter?

Perhaps Ginsberg was high (he was a lot of the time) and just did not remember what he did with the letter. Stern was an easy target. Literary magazines over the years took Ginsberg’s letter story as the gospel and Gerd was vilified for decades. Ginsberg’s pettiness and overindulgence finally was made responsible and Stern vindicated — rather late than never ever.

Thanks for your contribution, Mark. Neal Cassady’s “Joan Anderson” letter is a crucial document for anyone who cares about the Beats. Hopefully it will be published in its entirety soon. The last I heard was that it did not sell at auction, so perhaps this may take longer than we’d like.

You’re right that Ginsberg held contentious opinions and, often, grudges that made people feel they were on the “outside” of an exclusive club. Gerald Nicosia, whose Kerouac biography Memory Babe still reigns supreme in my mind, has written at length about this phenomenon, of which Ginsberg was not the only proponent. John Sampas, Kerouac’s brother-in-law, holds a great deal of influence as the literary executor of his estate, and has often used that power to steer the machinery of mythologizing the Beats to exclusionary ends. This has meant that many voices, most notably Jan Kerouac’s and Nicosia’s, and as you note, Gerd Stern’s, have been silenced along the way. It’s fortunate that Stern has been vindicated with the recent discovery of the manuscript.

We probably won’t ever know exactly why Ginsberg promulgated the myth that Stern tossed the manuscript off the houseboat. It’s certainly a mark of the poet’s pettiness, an unfortunate trait that Schumacher points out at times in his biography. Perhaps it’s also indicative of the larger exclusionary practices of Beat hagiography I outlined above.