Fuse Theater Review: Israeli Stage’s “Fertile” — Powerful Theater About Difference

Romona Lisa Alexander’s impressive talent for chameleonic invention is well-suited to this demanding script.

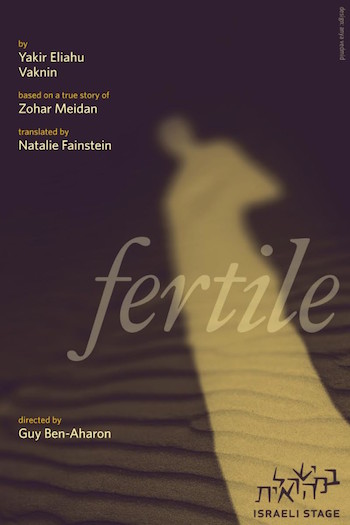

Fertile by Yahir Eliahu Vaknin, translated from the Hebrew by Natalie Fainstein. Staged reading directed by Guy Ben-Aharon. Presented by Israeli Stage at the Goethe Institut, Boston, MA on September 19. [Additional readings are scheduled for November 9 at Temple Israel of Boston, and November 22 at Newbridge on the Charles in Dedham]

Ramona LIsa Alexander in the Israeli Stage production of “Fertile.” Photo: Justin Saglio.

By Ian Thal

Script in hand, Romona Lisa Alexander mounted the stage at Boston’s Goethe Institut to perform Fertile, which was receiving, via Israeli Stage, its English language premiere. Fairly quickly the audience became comfortable with script’s dramatic approach, a terse exchange of voicemails alternated with the words of the protagonist, a woman named Fertile, who addressed herself in the mirror. She tells her reflection that she is “too beautiful” — and that she is “broken” — wrestling with questions of whether she can afford to risk living with the truth or without love.

Roughly one in one-hundred people are born intersex – that is with a reproductive or sexual anatomy or chromosomal composition that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male. (note: “intersex” is a broad umbrella term — it would be irresponsible to go into more detail about these conditions in a theater review.) Zohar Meidan, the actress who originated the role, and upon whose life Yakir Eliahu Vaknin’s Hebrew language script is based, is a woman born without a uterus, fallopian tubes, or ovaries. It is a rare condition that Fertile learns about while she still a little girl; followed by an admonition from her protective mother that she keep her non-existent organs a secret.

Fertile will never menstruate, and she quickly learns that she needs to lie to be accepted by her peers. And we see how she learns to lie effectively – it’s a slow process, made easier because teenagers rarely remember exactly what was said to them from one month to the next.

The teenage Fertile has no fear of pregnancy, so she feels free to be sexually available to the members of the high school swim team she is physically attracted to. But she discovers that she wants the intimacy of love as well as pleasures of lust. Yet she find that her lovers see her as being no more than a “good time,” perhaps because they see her as overly promiscuous, or too “fat” to be an athlete’s girlfriend.

The script offers neither a medical explanation for Fertile’s weight, nor does it pass a moral judgment. At one point the protagonist is unwittingly ‘fat-shamed’ by a character who thinks she is providing helpful advice to our protagonist. In truth, Fertile has greater self-acceptance of her size than she does of her lack of a uterus – perhaps because the former is a normative type of difference. As an adult searching for love, she has found a great guy who is attracted to fat women. Her deep fear that her infertility will be a deal breaker generates her self-loathing.

Alexander’s impressive talent for chameleonic invention is well-suited to this demanding script. An actor not only has to embody Fertile from childhood to adulthood, moving from the turbulent passage of the teenage years, but the variety of characters who are part of her story. Alexander meets these challenges with aplomb. She creates a wide range of voices, physicalities, and idiosyncratic gestures that give the play’s characters, no matter how briefly they appear, strongly-defined presences. There’s the well-meaning and nerdy girl scout leader Naomi, the earthy folk-medicine and magic practitioner, a bubbly and narcissistic sister, a sorrowful mother, and a physician too rational for her own good or the good of her patients. Alexander finds the comedy and tragedy in each of these figures; there’s a particularly strong moment when Fertile questions herself and her mother about why she go on.

Natalie Fainstein’s translation, as well as Alexander and director Guy Ben-Aharon’s staged reading, were faced with a decision: whether to Americanize the story or maintain the Israeli setting. The words mensch and kibbutz are used, but those were the only hints of the play’s national origin. Many of the struggles Fertile deals with are shared globally by women with fertility issues – especially those who are born with her rare anatomical condition. Menstruation serves as a means for bonding among women and girls across many societies, whether those cultures celebrate it or encumber it with taboos and shame. Still, Fertile’s story, when it was performed by Zohar Meidan for Israeli audiences, must have had a particular resonance. Israel has one of the highest birthrates in the developed world; even among the secular majority, happiness is measured in being fecund. In addition, there is the pressure after the Holocaust to replenish the world’s Jewish population, whose numbers have yet to recover to pre-1939 levels. That would not have to be spelled out for an Israeli audience – but it is an important subtext that may be lost in translation.

The talkback, which included remarks from Joshua Safer, the Medical Director of the Center for Transgender Medicine and Surgery at Boston Medical Center, prompted members of the audience to not only ask about treatments, but to offer their own stories about infertility. In a couple of instances, the anecdotes were about people they knew who shared conditions similar to Fertile and Meidan’s — and they faced the same the ostracism when their condition became known to the larger community.

Many contemporary cultural commentators, especially homegrown critics, are a bit too concerned that theater present “our stories” – they forget that drama is often at its most powerful when it elicits empathy with narratives about experiences of people who are different from us, who experience the world in a disparate way. In the capable hands of Alexander and Ben-Aharon, Fertile does just that.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.

Tagged: Fertile, Guy Ben-Aharon, intersex, Israeli Stage, Romona Lisa Alexander, Yahir Eliahu Vaknin