Theater Review: “Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education” — An Invitation to Take Action

Among the driving forces behind the unusual structure of Anna Deavere Smith’s latest solo work is a call to strengthen “our collective capacity for action.”

Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education, created, written, and performed by Anna Deavere Smith. Music composed and performed by Marcus Shelby. Directed by Leonard Foglia. Staged by the American Repertory Theater at the Loeb Drama Center, Cambridge, MA, through September 17.

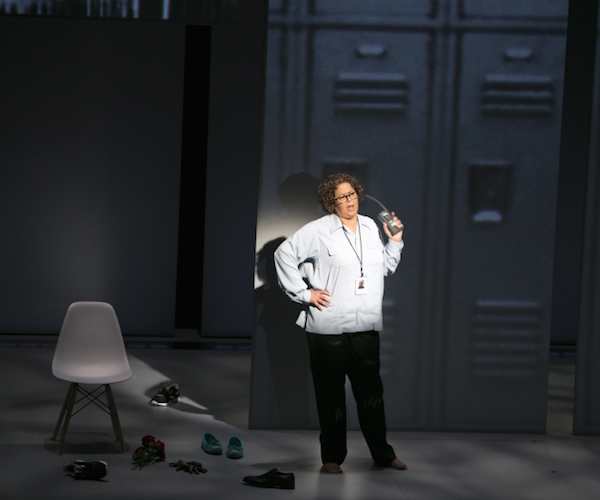

Anna Deavere Smith in “Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education.” Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva.

By Bill Marx

In his moving 2014 memoir Just Mercy, Byran Stevenson, the executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama, recalls that his first case, back in the early eighties, was helping to defend an African-American man unfairly condemned to death. It was in Monroe County, Alabama, the location of Monroeville, the birthplace of Harper Lee and the model for the sleepy town at the heart of her novel To Kill A Mockingbird. With an eye on generating tourist dollars as well as fostering civic pride, the citizens made great hay of the book and the Hollywood movie version starring Gregory Peck:

Local leaders turned the old courthouse into a “Mockingbird” museum. A group of locals formed “The Mockingbird Players of Monroeville” to present a stage version of the story. The production was so popular that national and international tours were organized to provide an authentic presentation of the fictional story to audiences everywhere.

Stevenson points out that, at the very time productions of To Kill a Mockingbird were condemning racism and generating empathy in swarms of appreciative/ennobled audiences, he was “busy working on the case of a innocent black man the community was trying to execute after a racially biased prosecution.” Infuriating? Ironic? Tragic? Depressing? The Way Things Are? What’s scary is that the facts about a host of alarming issues – the environment, the national debt and the annual government deficit, institutionalized racism — are in plain sight, yet not nearly enough is being done. Why not? [I would love to see a contemporary dramatist explore our collective pathology of denial. I am not holding my breath.] Does mounting a socially concerned theater ‘event’ – no matter how well-intentioned and informative — do more than make people feel good about themselves? Don’t they just return to their homes and tolerate/embrace the status quo?

According to American Repertory Theater director Diane Paulus, going beyond liberal feel-goodism and strengthening “our collective capacity for action” is among the driving forces behind the unusual structure of Anna Deveare Smith’s latest solo work, Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education. The production, which claims to dovetail Smith and the A.R.T.’s “shared mission to expand the boundaries of theater,” is made up of three parts: Act I is dedicated to exploring “the disturbing ways that public education in poor communities mirrors and intersects with the criminal justice system”; Act II splits the audience members into small groups for about 25 minutes to discuss questions generated by the play; a Coda features Smith in full inspirational mode, speaking the words of, among others, author James Baldwin and Civil Rights veteran John Lewis.

Of course, Paulus is far too savvy an entrepreneur to take up a social issue that might really challenge a Cambridge theater audience (i.e. the transformation of universities into corporations), which was mostly white on the night I attended. Does anyone in the vicinity believe that the struggle for Civil Rights is over? Anyone eager to argue for maintaining meagre educational opportunities, scant resources, and continuing mass incarceration of minorities? During my discussion period an older gentleman remarked that the problem with Notes from the Field is that it was simply “preaching to the converted.” That is spot-on. How could that be changed? A hard question to answer. Perhaps the A.R.T. might draw on its considerable resources and send this production to less politically friendly areas — in Blue states as well as Red states. Wouldn’t that generate lively, perhaps even volatile, discussions? Kick up a little real dust? Perhaps dedicate some stage time to current cases of educational injustice in the Boston area? Maybe name a few names? Make a few bigwigs uncomfortable? Shouldn’t political theater be willing to take some risks?

I have seen all of Smith’s other productions at the A.R.T. — she is a powerful performer, particularly when it comes to exploiting distinctive speech inflections, dramatizing the way vocalization shapes meaning. To my mind, this show isn’t up to her best efforts (Fires in the Mirror, Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992), though some of its problems will most likely be taken care of over the course of the run. Her delineation of the play’s different speakers is not as sharp or clear as it could be; no doubt Smith’s somewhat bland and unconvincing portrait of John Lewis will power up in the next couple of weeks and her Baldwin will become less cartoonish. I am old enough to remember when video images on stage were shown on television sets. In the A.R.T’s tech-happy hands, cable news footage is projected on large screens that stretch across the stage. At times, Smith seems to be dwarfed in this Big Brother setting. Bassist Marcus Shelby offers agile musical assistance, but theatrically he is a token presence, awkwardly integrated into the production. Occasionally Smith looks over to him for agreement or for a couple of words.

Anna Deavere Smith and Marcus Shelby in “Notes from the Field: Doing Time in Education.” Photo: Evgenia Eliseeva.

Smith’s focus in Notes From the Field also meanders. A section on the death of Freddie Gray is effective, particularly a powerhouse episode that draws on the galvanic words of Pastor Jamal-Harrison Bryant at Gray’s funeral. Still, I wish Smith had more fully explored the show’s ostensible subject — the insidious interconnections between education and prison. Finally, one of Smith’s great merits as a dramatist is that she brings together conflicting points of view, even opinions that are unsympathetic to a liberal audience. But for some reason there is little of that ideological expansiveness in Notes From the Field: we aren’t given the perspective of a policeman or a politician passionately asserting that things are the way they need to be. Her patient knack for exploring all the angles is what gives Smith’s approach, at its best, a touch of the tragic — the intractability of social problems embodied in the isolation of people who are absolutely convinced of the rightness of their point of view, trapped in their world of words.

As for going “beyond the boundaries of theater,” Shit-faced Shakespeare, a Magnificent Bastards production presented earlier this season by the A.R.T., ventures further afield than Notes from the Field. The former is at least unpredictable: an actor gets comically drunk on stage during a production of a play by the Bard. As for the latter, what of any surprising substance can be discussed in 25 minutes? The guide for my group talk was genial and concerned — the conversation was well-meaning but diffuse. Is there anything cutting-edge about putting the audience reactions before, rather than after, the final act … I mean Coda? Paulus is a whiz at branding, but even she can only get away with so much re-labeling, even in the now Broadway-ized world of the A.R.T.

At one point in the show, a principal of a high school in Philadelphia begs for our involvement, arguing that if each of us helped a struggling intercity student it would make a world of difference. It is a ringing ode to compassion, and Smith makes the most of these words. But is it only the pupils who need to be woken up to life’s possibilities? In his poem “Archaic Torso Of Apollo,” Rilke writes that art demands that “You must change your life.” Yes, the lives of far too many urban public school students need transformation — but given the decades in which this disgraceful situation has been tolerated, even encouraged, it could be that audience members need to change their lives as well. Perhaps commitment means more than just signing e-mail petitions or sending in checks. Perhaps it means consuming less and protesting more, taking the time to visit schools and organize tough-minded opposition, to put in the hard work necessary to create the support needed to sway or oust deluded or hapless politicians on the left and the right. Just a thought. Art is about metamorphosis, not just empathy. But we have not had many demands for radical change in the theater lately. Our stage artists are content to keep their audiences content.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.