Visual Arts Review: Photographer Diane Arbus – the Prequel

These photos give us more than a sense of what Diane Arbus would be doing for the last decade of her life, but also how her vision fits in with what her peers at the time were doing — observing the unobserved, perceiving the marginalized.

diane arbus: in the beginning, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Met Breuer, New York City, through November 27.

Taxicab driver at the wheel with two passengers, N.Y.C. 1956, Diane Arbus. Photo: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

By David D’Arcy

An exhibition of photographs by Diane Arbus (1923-1971) promises at least one or two ghastly frissons. We expect that her pictures will shock, and that promise of disturbance explains why Arbus tends to be the only photographer that most people can name — besides Robert Mapplethorpe, who also jolted his way into popular culture. Like Mapplethorpe’s pictures, Arbus’s are less jarring today — they have become a style, even a brand. We’ve seen them too often, or perhaps we think we have.

But diane arbus: in the beginning demands that we look again, although the exhibition is likely to fall short of upturning boilerplate expectations about this artist’s work. That’s not to say that the show is disappointing. It’s just that it serves up less — and more — Arbus than we’re accustomed to.

There’s less Arbus because the pictures on view aren’t the usual greatest hits displaying her in-your-face audacity. (Though some of her later pictures, which assert Arbus’s signature nerviness, have a room of their own.) The show gives us more Arbus because it broadens our view of her subjects and styles. There are images that have never been shown before, on view here thanks to the cooperation of the ever-wary Diane Arbus Estate, which selected the Met to be the permanent repository of the Diane Arbus Archive in 2007.

The museum’s selection of early works by Arbus (from 1956 to 1962) reflects a time when her marriage was falling apart and she had turned her back on a career in commercial fashion photography. It would not be until 1967 that the Museum of Modern Art first showed her pictures — 32 of them — in an exhibition of three emerging photographers — Arbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand.

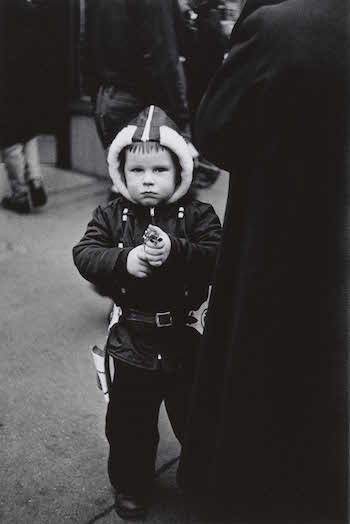

True to her later form, she’s capturing moments in the private lives of people on the street and other locations. She meets children who lack the guile to hide what they’re doing, like Kid in a hooded jacket aiming a gun, N.Y.C. 1957. She’s going backstage to meet women who take their clothes off for a living and men who perform dressed as women. She’s looking at people who, unlike fashion models, aren’t being paid to wear the clothes they are wearing. She’s eagerly entering a world where it’s normal to seem — or to be — odd. There are pictures of the peculiar people that Arbus and others called freaks.

To this exhibition’s credit, there’s more to react to than just those disturbing images. The variety of these photos give us more than just a sense of what she would be doing for the last decade of her life, but also show us how her vision fits in with what her peers at the time were doing — observing the unobserved, perceiving the marginalized.

And this contextualization is part of what sets this show apart from earlier Arbus exhibitions. It puts her into a time in the history of American photography when homegrown artists were grappling with European styles, such as street photography. Set boundaries between commercial and art photography were blurring. A handful of photographers dedicated to creating art (or at least attempting it) were making a living, thanks mostly to publications such as Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, and the New York Times Magazine. Who looks to those publications for visual inspiration today?

Galleries barely sold photography then. Arbus tried to make herself more marketable later in her short life — when she was already notorious, if not famous — by packaging ten pictures as a set for sale. The exhibition devotes a single gallery to those now-famous images – a Jewish giant at home in the Bronx with his parents, a boy holding a fake hand grenade, girl twins with radically different facial expressions against a white background, a female impersonator putting on makeup. Back then, few collectors bought them, even at rock-bottom prices, less than $100 a print. Museums tried to bargain those prices down.

Given the meagre rate of return, is it any wonder she was fearless? Add the suicide, her penchant for anonymous subway sex, and her hunt for the seductive photographic shock, and you have the enduring Arbus myth.

Diane Arbus. Kid in a hooded jacket aiming a gun, N.Y.C. 1957. Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Back to the early works. Among the pictures at the Met, Boy stepping off the curb, N.Y.C., 1958 is an image that’s sure to get attention, because it was published alongside a review of the Met exhibition in the New York Times. The photo of a child looking back at the camera seems inspired by European pictures of the 1930’s by such greats as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Brassai or Andre Kertesz.

You can see a variety of international influences in Arbus’s early pictures, such as Woman on the street with her eyes closed, N.Y.C. 1956, which suggests serenity as easily as it does despair. Her improbably meditative study in generic urban concrete, Puddle on the sidewalk, N.Y.C. 1957, is as close as Arbus gets to landscape. The photo feels like an homage to Cartier-Bresson, except that it lacks a man in the air leaping over the puddle. Arbus, the daughter of a family of merchants, grew up rich on Central Park West. She chafed at her upbringing. Perhaps that helps explain why she looked for (and found) something special in an ordinary sidewalk.

Besides the pre-war street emotionalism of an earlier generation of photographers, Arbus captures (or re-captures) a post-war sobriety here. The face of the child stepping off the curb has the composure and the resignation of a person who has already seen a lot (like that of the African-American weightlifter in A boy practicing physique posing at the Empire Gym, N.Y.C. 1960). It’s the same gray and grimy background you’ll find in city scenes by Arbus’s contemporaries, such as Weegee, Helen Levitt, and Robert Frank. A room in this exhibition of their pictures, alongside those by Arbus, suggests that this community of photographers influenced each other. Once again, you’re reminded that Arbus, stigmatized as a lone stalker of her subjects (which she was), had artistic company.

The light in Boy Stepping off the curb also reminds us that there was once life before Photo-Shop. The boy’s face is isolated in illumination against the grey background. So is one delicate hand, as it might have been in a baroque painting — and not just because the fair-skinned child looks as if he could have been painted by Anthony van Dyck.

Here Arbus seems to have it both ways: celebrator and exploiter. The picture gives us a delicate iconic figure transcending his dirty surroundings for a moment, or seeming to, as we see in her later work. But it also gives us Arbus opportunistically snapping the shutter, like a hunter or predator, when her victim appears. The ambiguity is part of Arbus’s experimentalism.

And innovation also drives her interest in ironically integrating old and new. Boy Steping Off the Curb is not the only photograph here that makes you think of a medium that predates photography. Couple arguing, Coney Island, NY, 1960 presents an ugly scene of an angry women yelling at her husband, who chooses to look away. Had he spent too much time on the Coney Island boardwalk staring at the mermaids? Who knows? — probably not Arbus. But the texture here of soft focus makes the picture seem as if it were done in charcoal. Millet and Daumier come to mind.

Blonde receptionist behind a picture window, N.Y.C. 1962 plunks a figure who could have been in an Edward Hopper painting into a maze of reflected surfaces. Arbus is not working with the sudden snapshot here, but wants to raise conceptual questions. Blonde, like many of the pictures in the show, focus on a lone (perhaps lonely) individual silhouetted against undifferentiated backgrounds. In Old Woman With Hands Raised in the ocean, Coney Island, N. Y., 1960, a female figure in the sea at a public beach lifts her hands up from the water — to be seen?

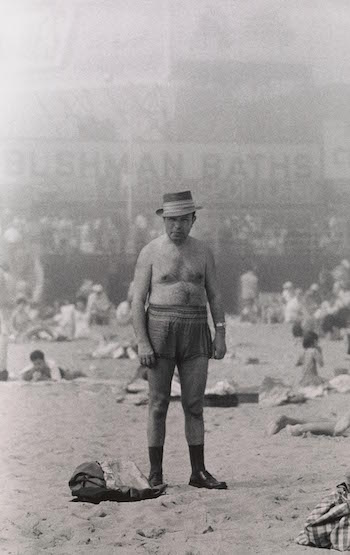

The woman in the ocean fits into another category; solitary figures who seem to be seen only by Arbus. (This sets these urban photographs apart from the still warm corpses and anguished victims of crime that are inevitably ringed by gawking onlookers in Weegee’s photographs.) Such is the case in Arbus’s Man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes, Coney Island, 1960. The picture feels transgressive, as if Arbus has just discovered the gentleman and is daring us to look at him, trunks and all. Or maybe she’s daring us to look away from him, as she almost always does in her later work. For critics, Arbus is about daring us to look, and it’s a fair enough assessment of how she approached some subjects, like this man, who seems transported to Coney Island from a Manhattan street with everything but his business suit. Here is a figure who could disappear among the masses at the shore, like a grain of sand in the vast expanse of beach on which he stands. There’s a curious empathy (or an empathic curiosity?) on her part that can’t be ruled out.

Diane Arbus, Man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes, Coney Island, NY. 1960. Photo: Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A subject to be pitied? Not when compared to slaughtered pigs hanging by their hind feet in a nearby Arbus picture, Dead Pigs Hanging, New York, 1960. Slaughterhouse pictures were part of the everyday Paris scenes that pre-war photographers gave us.

Influences in art can be tricky, but when I look at Man in hat, trunks, socks and shoes and its view of a loner in a clamorous crowd, I think beyond photography and fine art, toward the satirical comics of Robert Crumb, an acute observer of everyday anxiety. Who knows whether Crumb ever saw this picture? He certainly drew similar scenes.

Photography exhibitions, like most museum shows of paintings and drawings, tend to be installed on perimeter walls. When it comes to a photo show, it easy to feel as if you’re slowly scanning a contact sheet. You quickly become lulled into the monotony of repetition, especially if the prints are small. The MET’s exhibition design counters that conventional arrangement — each photograph is placed on the front or back side of a wide vertical strip. The strips are spread like thick, floor-to-ceiling poles — the distribution makes the gallery seem larger than it is. The set-up forces you to see each picture by itself. What’s more, the show is not organized chronologically; there have been the inevitable complaints from critics that Arbus’s narrative arc is being ignored. This is no dutiful march through Arbus’ early career, each image following and somehow begetting another. What you get instead is just as valuable — an invitation to scrutinize each picture’s distinctive narrative. And most of these images brim with references to art and photography.

One of my favorite pictures in the show, and one that bears a long hard look, is the deadpan Xmas tree in a living room in Levittown, L.I. 1962. It is an empty room featuring a Christmas tree, an American symbol with roots (a bad joke even back in 1962). The holiday scene also includes a television set, the portal to mainstream culture for all seasons. On the wall is a clock in the form of a futuristic star. This ‘star of Bethlehem’ is also the star of Levittown, a “planned suburban community” that represented a form of middle-class transcendence in post-war America, upward mobility for the families from New York City who moved there. This clear-eyed glimpse inside a modern dwelling is numbing rather than revelatory. There is nothing magical or intimate, as there is in Arbus’s visits to strippers’ dressing rooms, or in Robert Frank’s images of a continental journey in The Americans, which was published during these years.

Arbus’s unblinking ode to suburbia is a portrait of banality, an evocation of the emptiness that many found to the surprising reward for ‘making it.’ Most of her pictures would involve people, rather than deserted rooms. She would return to the suburbs for the series Family Albums, portraits of a nouveau-riche family that, while anything but flattering, suggest a bond between photographer and subject.

Our exposure now to so many previously unseen images doesn’t change what Arbus was, or what she became. It gives us a better sense of a transitional time when her work hovered between the commercial world – where her husband had his hand on the shutter – and the improvised world of art photography where she stalked some of her subjects and struggled to earn a living. If Arbus exploited her subjects, it was partly because she was determined to explore the new ways that post-war photography was observing (and discovering) everyday life.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Everyone will come at this show differently: as a freak show, street photography, a diary, or maybe just meddling with strangers. Having first seen her work with the publication of the early photos (“greatest hits”) we are, decades later, accustomed to her aesthetic: the odd moments, the strange subjects, the diary-like snapshots, the objet trouvé humans on display, the stubbornly black and white prints, the often unfinished look with the illusion of a snapshot. What astounded me with this show is how much deeper these new photos feel than the now easy satisfaction of the earlier group.

Over and over and over her parade of city life finds astonishing moments which are then, by dodging and burning meticulously in the darkroom, printed to perfection. The photos are small which renders them more like artifacts that you have to lean into and bond with. Her range from pure white to deepest blacks shows a mastes eye. Her appreciation of the slight and sly revelation of the psychology of the subject and the way the viewers must invest themselves in the ‘story’ of a person often in cahoots with the camera is intoxicating.

She even caught iconic moments from films she was watching in Times Square: a kiss between Eli Wallach and Carroll Baker in Baby Doll (though she never names the film – all the better) , a woman covering her the eyes as blood oozes from between her fingers – deja vu moments from a particular decade that speak to the thrill of movie-love.

Two of my favorites among many – A little boy hunched up grimacing for the camera as his little sister laughs at him hysterically; An old women all alone in a gray ocean and a gray sky – tiny in the frame – a perfectly developed picture where each finger maybe a millimeter long is in perfect focus as she bobs contentedly in the ocean. The only other object is a buoy way in the upper left. Lean in.

Susan Sontag declared in On Photography: “In teaching us a new visual code, photographs alter and enlarge our notions of what is worth looking at and what we have a right to observe.” Decades before the age of “here comes everybody” Arbus shot and then impeccably printed image after image of holy truth. This beautifully displayed show is not one to miss.