Book Review: “How to Listen to Jazz” — A Helpful Earful

Readers inspired to take a listening journey from Ted Gioia’s historical perspective will benefit greatly from how he delineates and discriminates among jazz’s various forms.

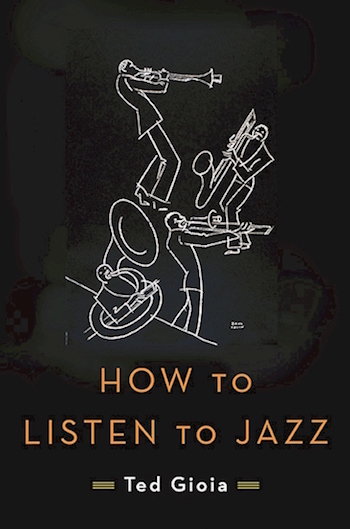

How to Listen to Jazz by Ted Gioia. Basic Books, 253 pp, $24.99 (hardcover)

By Blake Maddux

The prefatory quote to Ted Gioia’s new book How to Listen to Jazz comes from Duke Ellington: “Listening is the most important thing in music.”

This might elicit a “duh” from some readers, much like Yogi Berra’s quip about baseball that “You can observe a lot by watching.”

This juxtaposition of jazz and baseball is apt because, as Gioia explains, the word “jazz” first appeared in a 1912 newspaper article about America’s pastime.

But there is more to it than just that. Both of these deceptively sage pieces of advice convey the same message: do not overthink something that can be enjoyed or appreciated without being completely understood. As Gioia puts it, “[C]areful listening can demystify virtually all of the intricacies and marvels of jazz.”

Maybe so, but if we convert this quote into one about the aforementioned sport, “Careful watching can demystify virtually all of the intricacies and marvels of baseball,” Gioia’s guarantee about the ease of cracking the jazz code seems less certain.

After all, a baseball novice cannot simply watch (i.e., look at) what happens in a game and walk away understanding everything that transpired. One must not only watch, but know what to look for. Only then will he or she be able to truly observe a game.

So it is with jazz. Listening is surely the most important part of understanding this—or any—genre of music, but one must know what to listen for if one is to truly hear jazz.

For a budding enthusiast, a book called How to Listen to Listen to Jazz by a prolific and well-respected critic and historian who is also a musician should (ideally) provide useful if not definitive help at picking out what to concentrate on. The implication is that the more you know, the more enjoyment there is to be had.

Alas, Gioia falls a bit short of fully completing the mission that he set out for himself.

Gioia stresses that familiarity with music theory is not necessary to understand and appreciate jazz. One could say the same thing about this book. Granted, those possessed of such knowledge or who are familiar with the styles, artists, and albums on which the author focuses will have a head start. Either way, How to Listen to Jazz is perfectly readable for anyone who is the slightest bit inclined to immerse him/herself in a book with such a title.

What there is of jargon and music notation is more or less limited to chapters one through three. For example, in the third chapter (which is called “The Structure of Jazz”), Gioia breaks down three important jazz pieces into their multiple musical themes, the number of bars that each occupy, and the interaction among the several instruments involved. For better or worse, my eyes glazed right over these “music maps,” but that is certainly not to say that they will not be of value to those to whom they make perfect sense.

Elsewhere in the early portions of the book, Gioia offers several more morsels of concrete advice. These include, “Don’t just listen to the notes; listen to what the great jazz artists do to them,” learn to “‘feel’ the rhythms,” “conceptualize many jazz performances as an unfolding of four-bar units,” and “evaluate the authority and confidence with which [jazz soloists] begin and end their phrases.”

In later chapters, Gioia explains how styles of jazz that originated in different parts of the country were distinct from one another. “The saxophone,” he writes “shows up with increasing frequency in Chicago jazz bands.” In Harlem stride, the piano served as “as self-contained musical universe.” With Kansas City jazz, “The beat now moves from the snare and bass drum to the hi-hat” and “the upright bass becomes more assertive…”.

Some if not most of this advice can be fairly easily applied to most readers’ attempts to get jazz.

However, would one without at least some music theory training actually be able identify the “unfolding of four-bar units”?

What if that same listener wants to more fully grasp Jelly Roll Morton’s “artistry and aesthetic vision” but is reluctant to “take the trouble to explore the formal properties of his music”?

These questions suggest the overstated quality of Gioia’s claim that “the deepest aspect of jazz music has absolutely nothing to do with music theory. Zero. Zilch.” Perhaps this is true on a spiritual level or an imagined astral plane, but most people aren’t quite there yet. They might be able “to count to thirty-two and keep the numbers in time with the beats,” but that means only that they are—as Gioia puts it—“ready to roll.”

In fact, the author seems so eager to stress music theory’s lack of necessity that he throws out the much of terminology baby with the jargon bathwater, the former of which would have probably been helpful to those not quite ready for jazz at its most intense demands. By doing so, he does his readers a disservice by failing to untie the knotty technical elements that would have made learning what the title promises more challenging but also more rewarding.

Moreover, given that two-thirds of its easily digestible 220-some pages are about jazz history, its major players, and various subgenres, it seems that something along the line of Jazz: A Listening Guide may have been a more honest title.

But don’t get me wrong: Gioia’s knowledge of the genre is extensive and his passion palpable.

While he has exceedingly high praise for several who were born in or before 1926, including Louis Armstrong (“he had the biggest impact of anyone, and number two isn’t even close”), Ellington (who “sums up, better than anyone, the guiding concerns of this book”), Billie Holiday (“a diagnostician of the soul”), and Miles Davis (“If the twentieth century was the most restless age in the history of music, Miles Davis was its emblematic figure.”), he is not an old fogey convinced that there is nothing going on in the jazz world today that merits serious attention: “Whenever I hear people of a certain age grumble that nothing new is happening in music, I have to shake my head in pity. They clearly aren’t listening to the right stuff.”

Author Ted Gioia. Photo: Dave Shafer.

Readers inspired to take a listening journey from Gioia’s historical perspective will benefit greatly from how he delineates and discriminates among jazz’s various forms. They will also be given an assist in building a useful and extensive playlist by virtue of Gioia’s inclusion of “Recommended Listening” for each subgenre and “Where to Start” suggestions for each of several jazz innovators.

Still, I am not sure that I have come away from this book knowing, well, how to listen to jazz. And I feel, if I do say so myself, that I am the type of reader whom Gioia had in mind. I am a lifelong music fan, but mostly of rock and pop in their broadly defined senses. I was not in the high school band, cannot sight-read music, and am only somewhat capable of playing an instrument (guitar).

I have also gone through a couple of phases in recent years during which my enthusiasm for jazz was boundless. The first one was about five or six years ago, during which I learned about all the major artists and determinedly tracked down all of the generally agreed upon great jazz albums. I am in the midst of the second one now, and it may very well have been sparked a few months ago when I learned of the forthcoming publication of this book.

But it might be the case that I have not yet actively applied the suggestions that Gioia scatters throughout his book. A caution in the last chapter sets the challenge: “I may have given you a recipe book, but the obligation is on your shoulder to do the cooking and the tasting.”

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received an MLA from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

[…] Delta Blues, Work Songs, Healing Songs, and Love Songs. His book How To Listen to Jazz was reviewed here on The Arts Fuse. I talk to Gioia about his latest book, Music: A Subversive History, here. In […]