Book Review: Photographer Diane Arbus — Lingering Mysteries

“A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know,” Diane Arbus said. Her latest biographer notes that observation in his book. Hard as he tries, many secrets remain.

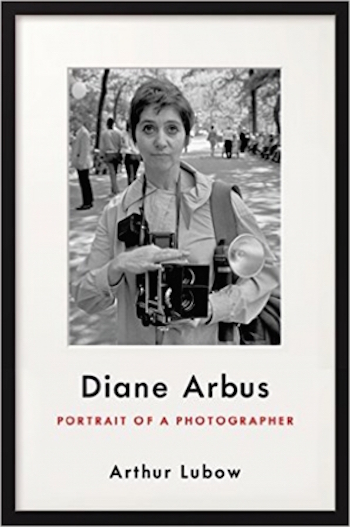

Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer by Arthur Lubow. Ecco Press, 752 pages, $35.

By David D’Arcy

When we think of Diane Arbus (1923-1971), and a lot of us will be thinking of her given that there is both a new biography and a much-anticipated exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, we inevitably see the subjects of her photographs, odd characters under the broad umbrella of what the public viewed as “freaks.”

There are strippers, nudists, a proud bearded dwarf, a Jewish giant in the Bronx with his parents, a grimacing boy with a toy hand grenade, a young man with a cigarette and his hair in curlers, twin girls who look like polar opposites, and asylum patients roaming the meadows of New Jersey. Even in today’s era of image overproduction, these are the pictures that still stay with us – a half-century after Arbus took them.

Arbus understood the shock of making us stare into unfamiliar, black and white worlds, illuminated by a flash bulb. Camera in hand, she would frighten beautiful women who posed for her into anger and dread. Norman Mailer, whom she photographed with his legs splayed apart, said that “giving a camera to Diane Arbus is like giving a hand grenade to a baby.” Yet she also made outcasts comfortable, or at least comfortable enough to have their pictures taken.

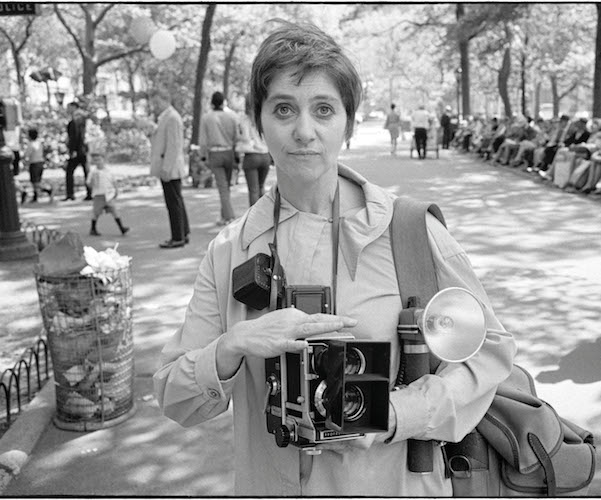

The central odd character in Arthur Lubow’s new biography is Arbus herself – waifish, wary, restless, conflicted, and adventurous – the creature we see in Ted Papageorge’s photograph on the book’s cover. It’s a sunny day in 1967 in Central Park, one of many places she habitually looked for subjects. A camera is hanging from her neck. Her dark eyes are wide open. The background is a mottled grey.

In Diane Arbus: Portrait of a Photographer, Lubow takes us into that deep grey area. Arbus had secrets, and she kept a lot of them private. What we learn here goes far beyond anything her pictures suggested. “A photograph is a secret about a secret. The more it tells you, the less you know,” Arbus said. Lubow uses that observation as the epigram for his book. Hard as he tries, many secrets remain.

Central among those secrets is her suicide at the age of 48 in 1971, the reasons for which remain the subject of speculation, all the more mysterious given that her work supplies a road map of clues.

For Lubow, the photographs obscure as much as they explain (the Diane Arbus estate denied him the right to publish any of her pictures in his book). Confronting that lifetime of images, the biographer finds himself forced into exploring the secrets of photographs that he’s been banned from showing.

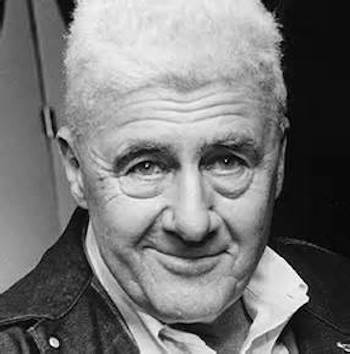

It’s been well-established that Arbus’s life generated plenty of drama. Diane Nemerov was born in 1923 into a wealthy Jewish family that found success selling furs and fashion at Russek’s department store on Fifth Avenue. But her father was a gambler and philanderer who didn’t leave much money behind after the business failed. Diane was a stellar student at Fieldston, a private school run by the secular Ethical Culture Society. So was her older brother, Howard Nemerov, who in 1978 would win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. For each of them, artistic brilliance would be overshadowed by painful self-doubt and emotional perversity. Lubow reports that the two siblings felt an intense rivalry with each other yet carried on a sexual relationship until shortly before Diane killed herself.

Arbus’ older brother, poet and critic Howard Nemerov. Photo: Poets.org.

The young woman started in photography in a partnership with her husband, Allan Arbus, an employee at her father’s department store. She married at 17 and the two made a living as fashion photographers, which may surprise those who pigeon-hole the enigmatic Diane Arbus as an observer of people branded as “freaks.” Two of her closest friends were models, or aspired to be. Her job was to style the models for photographs that Allan took. Diane Arbus complained about being required to photograph people wearing clothes that didn’t belong to them. She and her husband anguished over money – her parents didn’t leave her much. She also anguished over whether her pictures had any artistic value.

Photography was barely recognized as an art in the 1950’s, when Arbus found herself supporting two daughters as a divorced mother. Photographers were grateful to get lucrative fashion or commercial work. Richard Avedon, a friend of Arbus, made shooting models into a career. Even Robert Frank (The Americans) survived on it.

Soon, however, Arbus wandered out in search of other subjects – strangers in the park, children, random encounters. Lubow never lets us forget that the observant Arbus was also already on the prowl for sex, whether it was with strangers in buses and movie theaters or with the men whom she met through work. She told Frederick Eberstadt, another photographer, that she never turned down a man who wanted to sleep with her. Given the number of males who did bed her, it is surprising that we don’t hear from many of them — much of what we do learn comes from someone who heard something from someone. Much of this gossip has been reported before.

Street photography already existed on both sides of the Atlantic, but Arbus’s risqué exterior work broke boundaries. Some of her pictures seemed taken to surprise her subjects (and anyone who looked at the photographs). Yet she was anything but a drive-by shooter, often spending marathon sessions with her subjects, often clicking the shutter only when those sessions had become unendurable for the subjects.

That patient approach reflected the influence of one of her mentors, Lisette Model, who told Arbus to take a picture only after she saw something that excited her.

Arbus took vast numbers of pictures for herself. Lubow, who begins his long study with an overdramatized scene depicting her decision to abandon fashion photography, notes that much of her work throughout her career was done on assignment. Her best work, even toward the end, often began as journalistic assignments for magazines such Esquire or the London Times. Getting assignments was never very easy. Many of the ideas that she pitched to her editors were rejected. Some sessions because difficult because she could be as weird as her subjects, carrying a paper bag instead of a purse and talking about sex constantly.

It’s tempting to dismiss Arbus’s financial constraints at that time as the struggles of a poor little rich girl. She was born into wealth and even during rough periods, when she was scrounging for work, she lived comfortably by New York standards. The apartment in the Westbeth artists’ building, where she killed herself, was the envy of anyone who visited. Yet Lubow cites the fees that she earned to show how little anyone paid for photography back then. If the art market was tiny then, the photography market barely existed. When Arbus tried to sell individual prints to a handful of collectors in the few years before her death, she received about $100 for each one. Museums often told her they couldn’t even afford that price. When it came to finding sexual adventures Arbus was unfailingly enterprising — selling her work wasn’t among her strengths.

This was the absurd plight of an artist whose pictures were recognized at the Museum of Modern Art in a 1967 exhibition, “New Documents,” that featured three young photographers – Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander.

Arbus was at work on another show for MoMA — researching vernacular news photographs — when she took tranquilizers and slit her wrists in Westbeth in July of 1971.

Lubow takes us to that tragic end, tracking her privileged youth, sexual adventurism and struggles with money that were already well-examined in a 1984 biography of Arbus by Patricia Bosworth. At more than twice the length of that earlier book, this tome is a long march, especially without any images by Arbus. (We have to make due with descriptions.) Lubow examines Arbus’s work perceptively in the context of her teachers, Berenice Abbott and Lisette Model, talks about the influence of masters such as August Sander, Walker Evans, and Weegee, and evaluated her photography alongside contemporaries Robert Frank, Richard Avedon, Friedlander, and Winogrand. Yet he includes none of their photography. Eventually, a reader, tired of the blindfold, has no choice but to seek out a book with photographs that the Arbus estate authorized. Revelations, the catalog for a traveling exhibition that began at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 2003, is the most extensive, and Lubow quotes from it often.

(Arbus can also be seen and heard in a 30-minute documentary made in the year after her death and her insistent voice has a haunting restlessness in a 45-minute interview with Studs Terkel.)

To be fair, Lubow delivers some new information (actually exhuming unreported testimony) from Arbus’s conversations with her psychotherapist Helen Boigon in the years before her death. (These exchanges are taken from Patricia Bosworth’s notes). Here’s an example – “She was obsessed with sex the way a fat person is compulsively obsessed with food,” Boigon told Bosworth. “He stuffs himself and stuffs himself and is never satisfied, gets no gratification. Diane was like that, but worse. She could not connect with anyone or anything. That was what she wanted to be able to do. Reaching out and trying to connect, but she didn’t feel anything.”

We’re not told why Bosworth left that information out of her biography, or why a therapist spoke of a former patient with such indiscretion, including a wild description of Arbus trying to seduce her. The notes from conversations with Boigon also indicate that Arbus, caught up in a maelstrom of anxiety and money woes, was anguished over her relationship with Marvin Israel, an art director who supported her work at Harper’s Bazaar. While intimate with Arbus, the married Israel never left his wife, and Lubow reports that he eventually took up with Arbus’s daughter, Doon, who was then in her mid-twenties. Picturing that arrangement comes off as jolting as any Arbus photograph.

Diane Arbus. Photo: Tod Papageorge

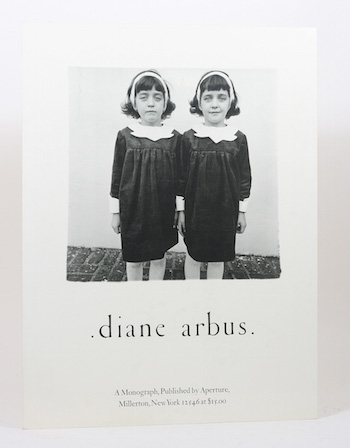

It was Israel who sent Arbus to a psychiatrist, as an attempt, Lubow writes, to “deflect her demands.” He shared a multi-story aerie overlooking 5th Avenue in the Flatiron District with his wife and a cat named Mouse – a stage perfectly set for melodrama. A merciless critic as well as a guide for the needy photographer, Israel knew Arbus’s work as well as anyone, and would assemble the most refined presentation of her pictures ever published, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph (1972).

If Israel is the Svengali/Salieri figure in Lubow’s biography, the role of fatherly mentor goes to John Szarkowski of MoMA’s photography department, who first acquired Arbus’ work in 1964 and organized a posthumous retrospective in 1972.

There’s a puzzling observation from Szarkowski, which comes after Arbus reflects on her experiences taking photographs of asylum patients in New Jersey, whom she visualized in white tunics and festive costumes against a background of expansive skies. The pictures offer rare glimpses of nature in her work and — uncharacteristically — her subjects seem at peace with themselves. That contentment made her uneasy, Lubow writes.

Of Arbus, Szarkowski remarked, “she was never a very depressed person in my presence.” More than anyone, he provided Arbus with the assurance that she seemed to need, plus the recognition that came from being shown at MoMA, and the income earned by her research for her upcoming exhibition on news photography drawn from city tabloids.

The professional reinforcement wasn’t enough. Others close to Arbus saw her usual restlessness turn more than a little desperate. Before taking her own life, Arbus, who always wrote neatly and legibly, decided not to leave a note. The reasons behind her demise would be her ultimate secret, one part of an expansive, tantalizing legacy of inscrutability that unites her life and her pictures.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.