Book Review: Marguerite Duras’ “Abahn Sabana David” — A Rush Job

Did Marguerite Duras, who had worked in the French résistance during the war, herself feel guilty about not having been sufficiently concerned, for quite some time, about the deep significance of the Shoah?

Abahn Sabana David, by Marguerite Duras, translated by Kazim Ali. Open Letter, 111 pp., $12.95.

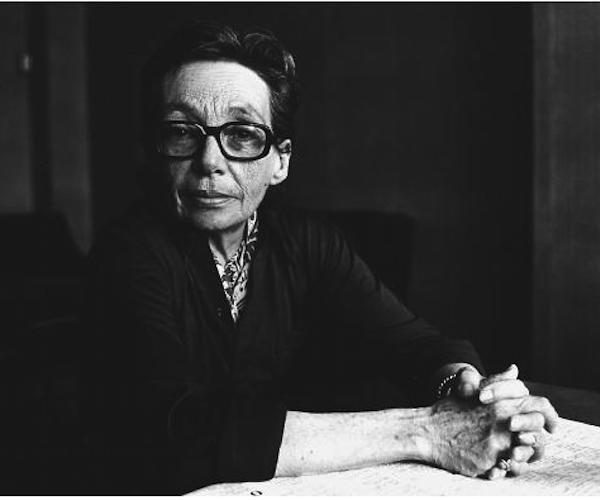

Writer Marguerite Duras — in the mid-1960s she became increasingly fascinated by Jewishness. Photo: Wiki Commons.

By John Taylor

Abahn Sabana David is not a well-known novel by Marguerite Duras (1914-1996) and, arguably, it is not even a novel. Published in French in 1970, the book—whose form much more resembles a play or a movie script—was indeed made into a film, Jaune le soleil, the next year. And although the actors (Catherine Sellers, Sami Frey, Michael Lonsdale, Diurka, Gérard Desarthe, and Duras’s son Dionys Mascolo) are all top-notch, Jaune le soleil likewise remains obscure in Duras’s cinematographic oeuvre.

Open Letter Books, thanks to the gifted translator Kazim Ali, has thus intriguingly unearthed this book from relative neglect and presented it, though too boldly, as a “late-career masterpiece.” In Duras’s prolific production, Abahn Sabana David is almost exactly a mid-career work, and, to my mind at least, it doesn’t quite stand up to Détruire, dit-elle, published in France the year before (and in Barbara Bray’s English translation in 1994 as Destroy, She Said).

It’s enlightening to read them together. Destroy, She Said is similar to Abahn Sabana David in formal ways, notably in its use of conversations between four main characters. The book was also made into a film the same year (1969), with two of the actors (Sellers and Lonsdale) who would later appear in Jaune le soleil.

Both books are representative of an evolution in Duras’s literary and artistic vision. Beginning in the mid-1960s, she started moving constantly between novel writing, filmmaking, and the theater, often offering both a novelistic and a theatrical or a cinematographic version of the same story. She is often said to have blurred the boundaries between such genres. Yet in Abahn Sabana David, it seems to me that she must essentially have kept in mind one artistic form—a film—and also inserted that form into a second form—a novel, even if the novel was issued first and probably served as the drawing board for the subsequent film. That is, with Abahn Sabana David, I have the impression that I am “reading a film,” not so much a “novel” for which scriptwriting techniques have been employed. But call it a “cinematographic novel,” if you prefer.

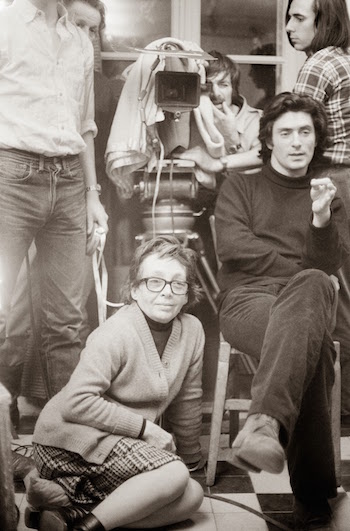

Marguerite Duras with Sami Frey on the set of “Jaune le Soleil,” 1971. Photo: Jean Mascolo/The Red List.

Consisting almost entirely of dialogues and of descriptions that resemble succinct stage directions, Abahn Sabana David sketches the story of Sabana and a younger man, David. They show up at a country house to find a man named Abahn. They are leftwing political party workers who are going to guard and perhaps even murder Abahn because of acts of betrayal that he has apparently committed. One learns little about the events that have brought these three characters together in this disturbing, sinister way, and hardly much more about their personal lives. The twenty-five-year-old David, for instance, is tersely described as being a stonemason and married to a woman named Jeanne. As to Abahn, he is simply called “the Jew.” And then another man—“tall, thin, graying at the temples”—arrives. He is also called Abahn and, just a little later, he designates himself as “a Jew.”

Given these two homonymous Jewish Abahns (the first of whom is always “the Jew,” but this distinction sometimes needs to be worked out by rereading), it is not always easy to keep them separate and follow dialogues which, when filmed or performed onstage, would be clearer:

[Sabana] turns then, gestures toward the Jew, resting his head on the table.

“I don’t think he’s crying.”

Abahn looks at the Jew.

“He is crying.”

She looks then at the one who is crying. Then the one who is speaking.

“He can’t be crying, he wants to live.”

“He’s not crying for himself,” says Abahn. “It’s an empathy for others that forces him to cry. It’s too much for him to bear alone. He has more than enough desire for himself to live, it’s for others that he can’t live.

She looks at him with interest, his white hands, his smile.

“Who are you to know all this?”

“A Jew.”

To Sabana, David, Abahn I, and Abahn II must be added two shadow (and shadowy) characters, Jeanne (“we’re afraid for Jeanne, night and day,” Sabana announces at one point) and Gringo, a powerful figure who “runs the show with the merchants. He runs the government offices. He has his own police, army, guns. He’s been making the merchants afraid for a long time now.” At the end of the story, Sabana announces, after a long silence: “I am Gringo as well. The female Gringo.”

Alongside the risks and retributions of political militancy, the even more salient element in this sometimes Sartre-like existentialist thriller is Jewishness. As in Destroy, She Said, where three characters (Stein, Max Thor, and Alissa) are designated as “German Jews,” Duras not only calls the first Abahn “the Jew” but also defines him as having survived Auschwitz. Sabana hails from the similarly sounding “Auschstaadt,” whereas Abahn’s remark that they are in fact all “from Auschstaadt” immediately recalls Daniel Cohn-Bendit’s now-proverbial remark, made during the May 1968 student uprisings in Paris, that “we [the protesting students] are all German Jews.” Duras was involved for a while in the May 1968 uprising and, given the dates, one imagines her beginning to draft her anti-capitalistic (and also anti-Soviet-communist) novel shortly afterwards.

The same years show her increasingly fascinated by Jewishness, a topic that has been researched and debated by specialists of her oeuvre in general and of Abahn Sabana David (and similar works) in particular. Sometimes, her fascination overwhelms other literary and intellectual considerations and her work loses some of its potential complexity. For example, as the conversation between the four characters of Abahn Sabana David progresses, the extermination of the Jews by the Nazis, during the Second World War, comes to symbolize a sort of “genocidal” present day (situated, probably, during the year 1968, when the Soviet Red Army invaded Prague, or its immediate aftermath):

Sabana has been quiet.

“Some say she’s Jewish,” says David. “That she came from far away.”

“From the German Jewry,” says the Jew. “From the town of Auschstaadt.”

David pauses. [. . .]

He turns to Sabana. Fear rises in her eyes. He asks her:

“Are you from Auschstaadt?”

They all look at her. She is frozen, sitting there against the wall, in the light. The clear blue eyes are unfocused: they seek Auschstaadt.

“Auschstaadt,” she repeats.

“Yes,” says the Jew.

“Where is Auschstaadt?” asks David.

“Here,” says the Jew.

“Everywhere says Abahn. “Like Gringo. Like the Jew. Like David.”

“Here. Everywhere,” says the Jew.

“And when?” asks David.

“Always,” says the Jew. “Right now.”

“We’re all from Auschstaadt,” says Abahn.

Listen carefully: Auschstaadt is “here,” “everywhere,” “right now.” Since there is no apparent irony in these remarks, a question must be raised: to what extent is it intellectually and literarily justifiable to apply Auschwitz, with all its gruesome anti-Semitic specificities, to a political, economic, social or international situation that is taking place some 25-30 years later and that is not the same tragedy? Literarily speaking, Auschwitz and Jewishness are used as catchall terms, as ready-to feel ambiences as it were, even as “Hiroshima” functions as a sort of haunting password in Duras’s gripping and desperate love story, Hiroshima Mon Amour (1960). But are there not fundamental aspects about Auschwitz that imply that this place name cannot function, as least not in the same way, as “Hiroshima” does in the earlier novel?

Of course, it could be argued that irony is nonetheless interwoven into the above-mentioned conversation and that Duras is showing how certain kinds of French leftwing intellectuals thought at the time, when they would ascribe terms like “Auschwitz” and “genocide” to many disparate varieties of human suffering. Their ideological blinders too often kept them from seeing reality objectively and with discernment; all fine distinctions were smudged away by the Communist party line or by that of the bien-pensant leftwing, the prototype of political correctness. Moreover, Auschwitz was “discovered” in France in the late 1960s and 1970s, after two or more decades of relative silence during which leftwing political discourse had been aimed at other topics: colonialism, the Vietnam War, and the like. Did Duras, who had worked in the French résistance during the war, herself feel guilty about not having been sufficiently concerned, for quite some time, about the deep significance of the Shoah?

Be this as it may, her overuse, in some passages, of Jewishness and Auschwitz builds a sort of screen preventing her (and us) from entering more deeply into the interrelationships of the four characters. Although her oft-admirable stylistic tone pervades these dialogues, Abahn Sabana David provides not the only case where the author perhaps drew her inspiration too quickly, not only from the political present or from a historical event whose full significance emerged only a few decades later, but also from her over-confident subjective “idea” of it—even as she once explained, in regard to India Song (book, 1973; film, 1975) that she had evoked “the India of her mind, her phantasm,” never the real India, “and had not even shown the beggar woman.”

John Taylor’s translation of Pierre Chappuis’s poetry, Like Bits of Wind, has just appeared at Seagull Books. He has also recently translated books by José-Flore Tappy, Georges Perros, and Philippe Jaccottet. He is the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature (Transaction Publishers). His most recent book of short prose is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press). John Taylor’s website.

Tagged: Abahn Sabana David, Kazim Ali, Marguerite Duras, Open-Letter