Film Preview: Silent Film Comedian Raymond Griffith — Sophisticated Slapstick

A rare opportunity to see — on the big screen — a film starring Boston-born silent comedian Raymond Griffith, a master of the debonair pratfall.

Raymond Griffith and Betty Compson in “Paths to Paradise,” screening at the Somerville Theatre this Sunday.

By Betsy Sherman

He was the most dapper, and unflappable, of Hollywood’s silent clowns. And he was born in Boston — though, as the child of actors, he might as well have been born in a trunk. Raymond Griffith makes a celluloid return to the area with the Sunday, May 15, 2 p.m. screening of Paths to Paradise as part of Somerville Theatre’s Silents Please series with musical accompaniment by Jeff Rapsis.

Griffith and the wonderful Betty Compson co-star as jewel thieves whose attraction to each other doesn’t preclude some down-and-dirty competition. The 1925 feature’s premise anticipates Ernst Lubitsch’s 1932 Trouble in Paradise. This one, however, builds to a raucous car chase towards the Mexican border.

In his indispensable The Silent Clowns, Walter Kerr devoted a chapter to Griffith and gave him fifth place in the eponymous pantheon, after Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd and Harry Langdon. Griffith’s trademark look was a top hat and opera cape, with mustache neatly trimmed. Sadly, however, most of Griffith’s features are among the silent period’s lost films. We have Hands Up!, a very funny 1926 Civil War comedy in which Griffith is sent by Robert E. Lee to secure a gold mine for the Confederacy, and Paths to Paradise. The latter survives, but it’s not quite complete The last of its seven reels was lost to deterioration, but it reportedly ends in a plausible place. The Somerville will be showing a restored 35mm print from the Library of Congress (and there will be an explanation of what the ending was, once the picture is over).

The part Griffith played in Hollywood history, in front of and behind the camera, is an interesting one. In a sense, silent movies were made for him, just as he became important to them. He gained experience on stage as a child actor, but by the time he became an adult his vocal cords had been damaged, and his voice was a hoarse whisper. He used to tell people that it was because, in a play called The Witching Hour, he had been made to scream repeatedly. But research has shown that it was from having contracted diphtheria as a child. Before he broke into the movies, Griffith toured Europe with a French mime troupe and was a professional dancer. The result of this training can be seen in his grace as a comic actor.

After he appeared in some shorts for an outfit called L-KO (Lehrman Knock-Out), Griffith was grabbed in 1916 by the king of slapstick, Mack Sennett. Along with becoming a player in Sennett’s churned-out shorts, he became one of the studio’s premiere gag-writers. He then played supporting roles in features made by Samuel Goldwyn and Universal. The actor signed a contract with Paramount in 1924 and worked his way to starring status.

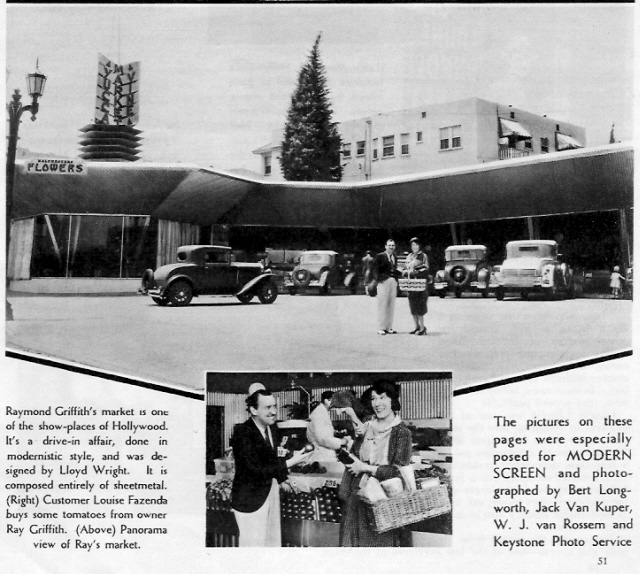

A magazine piece on Raymond Griffith’s market: “One of the show-places of Hollywood. It’s a drive-in affair, done in modernistic style, and was designed by Lloyd Wright. It is composed entirely of sheetmetal. (Right) customer Louise Fazenda buys some tomatoes from owner Ray Griffith. (Above) Panorama view of Ray’s market.

Kerr describes a favorite Griffith performance as one in which he stole the picture playing a character who grabs every opportunity to curl up and sleep. He was not exactly the clamoring-for-attention type of funnyman. In Paths to Paradise, he doesn’t even really have a name. His character, the Dude from Duluth, is such a slick con-man that he has a whole portfolio of identities. The movie’s source was a play, The Heart of a Thief by Paul Armstrong (it was adapted again in 1945 as Hold That Blonde, with Eddie Bracken and Veronica Lake). It was directed by Clarence Badger, who also made Hands Up! and the Clara Bow classic It.

With the end of the 1920s came the transition to sound films, and Griffith’s days seemed numbered. He made two sound shorts; in one, the comic premise involved him having respiratory problems. His friend Howard Hawks was to direct him in his first talking picture, but the movie in question, Trent’s Last Case, ultimately was made as a silent. Griffith did appear in one of the great early-sound-era films, All Quiet on the Western Front, in an important non-speaking role as a French soldier killed in a foxhole by the young German protagonist.

Griffith went on to a busy career as a writer and producer associated with Darryl F. Zanuck; he followed Zanuck from Warner Bros. to Twentieth Century Fox. Fun fact: Griffith owned a modernistic drive-through grocery store, Yucca-Vine Market, designed by Lloyd Wright, son of Frank Lloyd Wright. The erstwhile clown came to an odd end, dying of asphyxiation after choking on food at the The Masquers Club, a social club for actors, in 1957 at age 62.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Betsy Sherman, Betty Compson, Jeff Rapsis, Paths to Paradise, Raymond Griffith, silent comedy, silent film