Book Interview: Edgar Allan Poe — America’s Maestro of Suffering

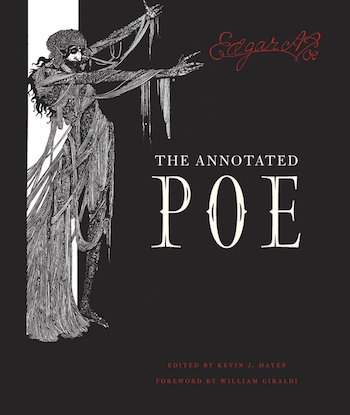

The Annotated Poe invites readers to take a fresh look at Edgar Allan Poe and his far-ranging artistic legacy.

By Matt Hanson

It’s safe to say that the Boston-born Edgar Allan Poe has one of the most powerful posthumous reputations in all of American literature. His works have inspired the likes of everyone from the great decadent Charles Baudelaire, who venerated and translated Poe for eager French readers, to Bob Kane, who began musing about a mysterious superhero dressed in a black cape after a visit to Poe’s house in Baltimore. Lou Reed, Iggy Pop, and Jeff Buckley have each recorded tributes to his poetry and fiction. The Baltimore Ravens football team is named after his poem. Our cultural Poe obsession only deepens when you consider the mountain of films, paintings, and comics directly inspired by Poe’s bizarre and ghoulish cast of characters.

All of this name-dropping reinforces the popular iconography that’s built up around the man himself. Poe’s instantly recognizable face can be easily used to symbolize the suffering artiste, the haunted romantic, or mad genius, as needed. The problem with this adoration, of course, is that the popular hype surrounding Poe’s reputation magnifies the outré legend but sells the actual writing short. The sad fact is that “The Raven” has become the literary equivalent to “Stairway to Heaven” and tragically dissuades readers from considering Poe’s work as a whole.

By giving Poe the scholarly attention he deserves, Harvard University Press’s beautifully designed new edition The Annotated Poe combats the demeaning cliches. Novelist and critic William Giraldi’s foreword elegantly places Poe within his historical, biographical, and critical context. Editor Kevin J. Hayes picked a savvy selection of tales and poems and provides richly detailed and deeply insightful notes that consistently add complexity and depth to the texts. The beautiful illustrations from all manner of media amplify some of the more ethereal of Poe’s imaginative creations. This new edition invites readers to take a fresh look at Poe and his far-ranging artistic legacy.

As a writer, Poe was very much ahead of his time. He was not merely a scribbler of spooky tales anxious to keep his meager income trickling in, or a moon-eyed romantic murmuring alliteratively over cob-webbed tombs. The Poe that emerges from the annotations in this volume is a far-sighted and rigorous craftsman who prefigured many modern literary trends. His writing career was marginalized (and belittled) before his premature and still mysterious death, but Poe’s uncanny visions and prophecies, discovered as he poked and prodded through the labyrinth of consciousness, now make him our contemporary.

Monsieur Dupin, Poe’s implacable detective, is an acknowledged forerunner to Sherlock Holmes, whose prodigious use of reasoning powers unravels the puzzle of the criminal mind. The sinister double who never leaves William Wilson inspired both Dostoevsky’s and Robert Louis Stevenson’s more famous doppelgängers. Several filmmakers and theorists, such as Jean-Luc Godard, consider “The Oval Portrait” to be one of the earliest forerunners of film theory. Moody set pieces like the urban, voyeuristic “The Man in the Crowd” hint at the existential aesthetics of noir.

His specialty was exploring the mechanics of a certain kind of insanity. Poe’s obsession with the psychology of guilt and repression, on the spells cast by dreams and fakery, particularly as they relate to the duplicities of language, fits in uncannily well with the arrival of Freud. Whether it’s casks of amontillado, murders in rue morgues, or tell tale hearts, his fiction revels in psychic claustrophobia and the climactic return of the repressed.

Nobody understands how to dramatize the madman in full-throttle confession quite as well as Poe. In their manic logorrhea, his murderers and crazies are interestingly postmodern. Perpetually claiming to disclose secret truths about themselves, these erratic narrators immediately tend to backtrack, questioning their own motives and the truth of their own testimony even as they rattle off what they purport to be the facts, ultimately revealing their revelvations to be part of a convoluted artifice made up of (infinite?) false bottoms. Part of the way madness works in Poe is in showing the limitations of what it means to be sane.

The Arts Fuse recently caught up (via e-mail) with William Giraldi to ask some questions about his foreword to the collection as well as to speculate about some of the enigmas of Poe.

Arts Fuse: One of the first things you notice from the notes in this edition is the range of Poe’s references- quotations, translations, and allusions from all kind of literature abound. Do you think Poe had a deeper purpose for this, was he showing off, or what?

William Giraldi: Like any serious and important writer, Poe processed the world through the lens of literature. Literature was, for him, a way of seeing, and he understood that without an immersion in the classics, without deep reading, and the marshaling of that deep reading, his own work would always be sapling. The myriad allusions and references you mention are actually the opposite of showing off: they are an homage to the greats that came before, a humbling of oneself at the altar of literature. Auden has that great line: “About suffering they were never wrong, / The old Masters: how well they understood / Its human position.”

Poe was a maestro of suffering and so it makes sense that he would reach into the annals of literature, that his work would grapple with what has already been asserted and expressed. And I would argue that literature is, or should be, primarily about itself. Joseph Brodsky speaks about writers being in a competition with all the great work that came before, and I’m certain that Poe felt that.

Novelist and critic William Giraldi.

AF: Another constant theme in Poe is his interest in the exotic. He sets many of his stories in far-flung locations (some of which he clearly doesn’t know from experience, such as Paris). What do you think compelled him to do this? Is he playing to the escapism of the reading public, or is something deeper going on?

Giraldi: Part of the answer can be explained by his storytelling sensibility, and its need for exoticism, yes. Poe wasn’t interested in the waking world, the quotidian, the domestic. Naturalism struck him as a supreme waste of time. It’s true, as you suggest, that the nineteenth-century American reading public quite enjoyed exotic locales, but there’s something else happening there, and perhaps something of which Poe wasn’t himself entirely conscious.

I mean he had lots of problems with America, with his fellow Americans — he thought his countrymen hopeless dullards — with what he considered the rabid injustices of American economics, the lie of the American Dream. In other words, he felt let down, he suffered terribly, and so felt no loyalty to American values, no compunction to be an “American writer.” Many of his tales are set on foreign and imaginary soil in what I would call an act of defiance.

AF: In your foreword, you note a “tantalizing” possible comparison of Poe with Kafka.

Giraldi: It’s curious that our two most important writers of the night, men with similar temperaments and dispositions, could be so stylistically different. One would never mistake a Poe sentence for a Kafka sentence, and yet there are times when I’m reading Poe and can’t keep myself from seeing the nexus to Kafka’s sensibility, and times when I’m reading Kafka and can’t help but feel Poe’s presence, his ghost in the lines.

I mean they are both about constructing an ostensibly alien cosmos that nevertheless seems just right, seems to be the very cosmos we inhabit. Their inky interiority, their beyond-black humor, their tremendous poetics of suffering: they are kin. It would take a book to detail their particular kinship and I wish some sharp critic would set himself to the task.

AF: A lot of reactions to Poe throughout the ages make inferences about the man himself — you mention that D.H. Lawrence assumed Poe really was a vampire, rather than just writing about them — and the book is chock-full of different depictions of the man in a variety of media throughout the ages. Do you think that this biographical interest would be something Poe would approve of or would be want more of a distance between himself and his literary work?

Giraldi: Poe would have approved of anything that would have made him some money, such was his desperation. He would love to see himself so celebrated across media, I think. He would weep to see how famous and well-regarded he is. He struggled for that recognition throughout his entire career, but was never paid enough, never taken seriously enough, not when you compare him to a writer such as Longfellow, whom he resented, if not detested.

This conflation of the writer with his work is just something we like to do. Poe isn’t the only target of that fallacy. As readers, as a culture, we can’t help but be interested in personality, the persona behind the fiction. It’s true that Poe gets it more intensely than most, but if that brings people to his singular work, it’s okay by me.

AF: A lot of Poe seems deeply embedded in his personal obsessions, yet his work has attracted an impressive public. Is that something Poe is consciously aiming for in his writing or more of a happy accident of posterity?

Edgar Allan Poe — D.H. Lawrence assumed Poe really was a vampire, rather than just writing about them.

Giraldi: I’d argue that every strong imaginative writer composes from the roiling depths of personal obsession. I mean he doesn’t have a choice in that. Now, obsession is by its very nature highly idiosyncratic and bulletproofed against rationality. One definition of literature, or one mission of the literary writer, is the transference of the personal into the universal, though Poe appears to be working in the other direction: from the universal to the personal. His problem was that he wanted/needed a large audience but didn’t have Longfellow’s talents for wide appeal.

No writer controls how his work is received, and especially not by posterity. Poe’s work is a mite repetitive, as you’d expect from a natural obsessive, while also being profoundly dark. It’s something of a mystery, perhaps, that Poe is so widely known and loved when you consider how demoniac, how downright disturbed the work is. Many of his fans are attracted to the man behind the work, though they wouldn’t have liked him very much. He was an impossible person, possessed in all the right and wrong ways.

AF: In your foreword, you call Poe the saddest poet who ever lived. That’s quite a claim, considering the other sad-sacks in poetic history.

Giraldi: He was never not aware of his suffering. It’s in the letters, the poems, the tales, the essays, the marginalia. I don’t think he was being merely Romantic in that suffering, merely posturing. (In many ways, his work is a repudiation of the Romantic.) He witnessed his mother die when he was just two. He was ripped away from his siblings. He grew up beneath an unloving and glacial man, John Allan. His cousin-bride died, like his mother, at the age of twenty-four. His brother drank himself into the grave at twenty-four.

He was simply encircled by death, could not get away from it. Forever ill, underfed, under-appreciated, yet aware of his own genius: he had a tremendously sorrowful life. You might say that such a sorrowful life gave us an indelible American literature, the first real American literature, as William Carlos Williams maintains, and so it was worth it, all his sadness. I happen to believe that nothing is worth sadness, and if I had the power to make a trade, to make a choice, his contentment or his art, I would choose his contentment.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: Edgar Allan Poe, Harvard University Press, Kevin J. Hayes, Matt Hanson, The Annotated Poe

Admittedly, satisfying all of Edgar Allan Poe’s admirers would be difficult, but I am disappointed that one of my personal favorites among his psychological fables, “The Imp of the Perverse,” is not in the HUP collection. It is a diabolical tale about the unconscious will-to-destruction that presages Dostoyevsky and Freud.

Yeah, I was disappointed with that too. It is a shame, since despite its density it really does hit on many of Poe’s thematic concerns and definitely captivated me when I read it by chance years ago. Another example of Poe’s work being much farther ahead of his time than was good for his career.