Dance Review: Sampling the Spectrum — BB@Home, Boston Ballet School

Sunday afternoon’s hourlong program in BB@Home series took us from the nineteenth century to this very minute.

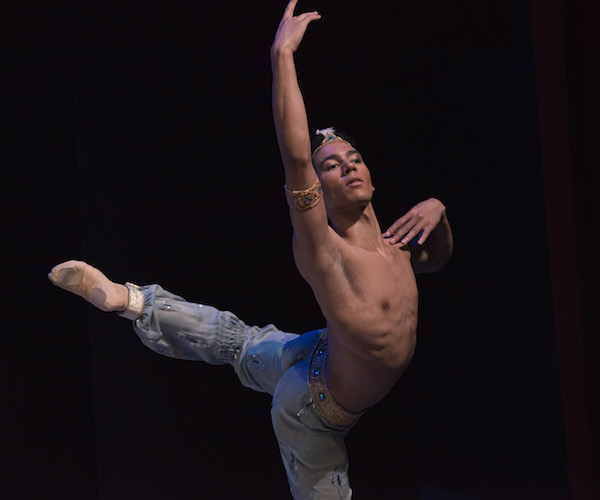

Desean Taber in Marius Petipa and Ivan Liška’s “Le Corsaire.” Photo: Igor Burlak, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

By Marcia B. Siegel

The second installment of this season’s BB@Home series sampled the history of ballet choreography while showing off the dancers of Boston Ballet II. Introduced by associate artistic director Peter Stark, Sunday afternoon’s hourlong program took us from the nineteenth century to this very minute—with a new dance made for the junior company by BB dancer Boyko Dossev.

The assortment, nicely chosen for variety by Stark, illustrated the changing uses of ballet dancing. Modes went from the mildly flirtatious behaviors of the mid-nineteenth century to the grand postures of the Russian Imperial style, to flashy folk adaptations, to the sexual games of the 21st century. It seemed to me that the dancers paid more attention to executing steps than to the stylistic and musical nuance in these cultural frameworks.

Stark had staged the first three excerpts from longer story-ballets, all created before 1900. La Vivandière was choreographed in 1844 by the important French ballet master Arthur Saint-Léon. The whole ballet, with its thwarted-love plot about a peasant girl and her three contending suitors, was constructed around Saint-Léon’s wife, the irrepressible ballerina Fanny Cerrito. It lasted in the Paris Opera repertory until 1872. Various showpieces were lifted out and performed separately, including the Pas de Six.

Saint-Léon, in addition to choreographing and dancing, developed his own notation system, and wrote down the Pas de Six. He apparently didn’t notate the rest of the ballet but this invaluable recorded fragment, translated into modern notation, served to bring La Vivandière into our time. Its Pas de Six was retrieved for the Joffrey Ballet in 1977 by Ann Hutchinson Guest, and was set by the French director Pierre Lacotte in 1979 for the Kirov. The BB II version was based on those productions.

Sam Ainley and Erin O’Dea in Boyko Dossev’s”Ne Me Quitte Pas.” Photo: Igor Burlak, courtesy of Boston Ballet.

La Vivandière is virtually the only surviving example of the French romantic ballet style, which emerged during the same period as the French-Danish style of the great choreographer August Bournonville that has persisted for 150 years in Copenhagen. The romantic ballet as exemplified by these two choreographers is different from the classical ballet that came after it. The technique is modest, with lots of intricate, articulate footwork but a sparing use of the full pointe, a buoyant upper body, and a connectedness among the steps so that the dancer seems to be in constant motion. Today’s dancers don’t get much chance to practice phrasing that crams so much into the music; it requires dancing small, when the audience wants to see action that’s big. Sunday’s cast, headed by Aaron HIlton and Angela Bishop, didn’t quite offer the clarity that the step vocabulary needed.

Le Corsaire has been rechoreographed and excerpted so many times that tracking it down is nearly impossible. The cumbersome plot has pirates, a slave auction, and Medora, a beautiful Greek girl sold into slavery. The story is so pastichified and politically touchy now that it’s often scrapped in favor of smaller showpieces. Peter Stark credits his staging to Marius Petipa and Ivan Liška, and it’s just been announced that Liška’s full ballet will be performed by Boston Ballet next fall at the Opera House.

The ballet was made originally at the Paris Opera in 1856 by Joseph Mazilier. Petipa’s many Russian Imperial versions and revisions date from 1858 to 1899, and Liška’s version was made for the Bavarian State Ballet in 2007. Actually, in 1997 Boston had another full-length Corsaire, directed by Anna-Marie Holmes, which soon migrated to American Ballet Theater. Instead of the complicated full-length plot, Corsaire is often represented by showy interludes; the Pas de Trois is one of them.

Since we can’t know exactly what the classics are, you can’t blame the dancers or the audience for boiling it all down to jumping and spins. In Corsaire, Desean Taber was splendid as Ali, the slave, leaping around the space, doing all the heavy lifting of Medora (Erin O’Dea), then dropping to his knees to pay her homage, while the Pirate, Conrad (Samuel Ainley), partnered her gallantly but discreetly.

BBII dancer and trainees of Boston Ballet School in Arthur St. Leon’s “La Vivandière Suite.” Photo: Igor Burlak, courtesy of Boston Ballet

A lot of the early ballets revolved around class distinctions: kings and slaves, peasants and nobles, homebodies and exotics. Revolutionary Russian ballet took up this theme to glorify the proletariat. Flames of Paris (1932) choreographed by Vasily Vainonen, had another elaborate plot that Stark excerpted for a men’s duet. Apprentices Lex Ishimoto and Ashton Roxander danced this jumping marathon.

Later in the afternoon, an eight-man corps of trainees from the BB school did the Sailor Dance, restaged by Alla Nikitina after one of the most famous of the early Soviet ballets. The Red Poppy (1927) was choreographed by Lev Lashchilin and Vassili Tikhomirov, and re-choreographed many times after that. The public loved The Red Poppy, though it was criticized for using lowbrow dances and devices. On Sunday the nine Sailors did a vigorous, folk-inspired line dance. Its showy coordinated jumps and squats may have been a prototype for the touring repertory that stunned the world via the Moiseyev Folk Dance Ensemble, which got started in the mid-1930s.

Skip to the 21st century, when all this ballet-character business boiled down to relationships unencumbered by plots. Jorma Elo, resident choreographer for Boston Ballet, specializes in dysfunctional lovers, as seen in his three-couple Over Glow, made in 2011 for Aspen Santa Fe Ballet. Sunday’s performance was excerpted from a longer piece along Elo’s now-familiar clutch-chase-and-smooch lines. The part we saw was set to Mendelssohn’s Italian Symphony but the dancers didn’t seem swayed by the music.

Boyko Dossev’s ballet, Ne Me Quitte Pas, was based on Jacques Brel songs and he did seem to have heard Brel’s love laments. With soft shoes, relaxed upper bodies, and minimal use of turnout, the ten dancers had a contemporary look and so did the movement. The sections featured, first, three struggling couples. Then three men and a woman seemed to be in a competition over a tailcoat. They all danced together at the end. The audience screamed with pleasure and encouragement.

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.