Music Review/Commentary: David Bowie’s “Blackstar” and Norbert Stein’s “Das Karussell” — When Words Rule Music

Both David Bowie and Norbert Stein present distinctive and subtle approaches to the hybridizing of poetry and music.

A scene from a short video filmed for the release of David Bowie’s album “Blackstar.”

By Steve Elman

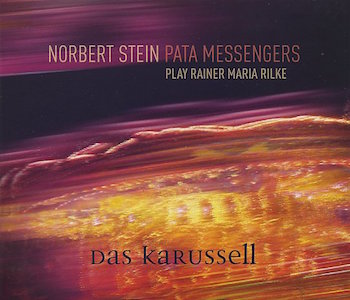

Two new CDs offer bold adventures in the continuing quest to juxtapose music and poetry. David Bowie’s Blackstar is the one you surely know about already, a dramatic final statement from a world-famous artist who defied expectations to the end. Norbert Stein’s Das Karussell, released in Germany on Stein’s own Pata label, is an illumination of poems by Rainer Maria Rilke, gratifying and muscular, from an artist whose previous work was completely unfamiliar to me. They are quite different in sensibility and execution, but they both draw from the jazz tradition, and they share at least two cautions to potential listeners: take this stuff seriously, and listen with both ears if you want to understand.

Bowie was as much a poet as he was a performance artist and a pop star, and his poetry is central to Blackstar. Stein is a jazz saxophonist and composer who generated the music of Das Karussell from the images and ideas of Rilke; even though the poems are spoken rather than sung on his CD, they reverberate through the instrumental performances that follow them.

Bowie’s last CD, written and performed while he was staring death in the face, does not deliver what you might expect. There are no exhortations about not going gently into that good night, no meditations on the skull of Yorick, no blank stares into an open grave. Instead, it consists of five stark mini-dramas that feint at finality, followed by a meshed pair of songs that just might be farewells. The words are printed black-on-black in the CD booklet, daring the listener to read them, forcing the reader to hear them slowly: “Skull designs upon my shoes / I can’t give everything away.” “In a season of crime none need atone.” “This way, or no way / You know I’ll be free.” “If I never see the English evergreens I’m running to / It’s nothing to me.”

Blackstar can be seen as a companion piece to 2013’s The Next Day, something like a yin to its yang. Bowie’s casual fans are more likely to be pleased by the latter, since it has more conventional tunes, less dense lyrics, and plenty of drive, despite Bowie’s anger at damn near everything that was going on in the world at that time. If you wanted to, you could listen to The Next Day with only half an ear and enjoy it. But Blackstar requires full listening for any kind of appreciation. True Bowiephiles will give it that kind of attention, but others surely will not. Listening to music, after all, has become an activity most often undertaken while doing something else – driving, cooking, cleaning the house, doing your taxes, etc.

If heard as background, Blackstar might disappoint. Its mood is primarily dark, and despite rock-solid drumwork by Mark Guiliana (and Boston-based drummer James Murphy on two tracks), this is an album of serious words. It has serious music to match, from a quintet of jazz players led by tenor saxophonist Donny McCaslin, including guitarist Ben Monder and McCaslin’s three regular bandmates, keyboardist Jason Lindner, bassist Tim LeFebvre, and Guiliana. All these players bring their distinctive jazz abilities to the material without forcing the music away from its essential character, and Monder keeps the guitar parts particularly well-rooted in rock. No one moment of the CD identifies it as “jazz,” although a good deal of it is jazzish. For example, two of the songs (“Sue,” where Murphy is drumming, and “’Tis Pity,” with Guiliana) build to a furious intensity in which the jazz skills of the players allow them to burn and float simultaneously, a quality that rock-trained musicians rarely achieve.

Blackstar isn’t background music, no matter how that’s defined. The compositional structures are rich and thick, with plenty of ambiguity suggested by spots of near-polytonality, harmonic contrasts on the tunes’ “bridges,” and dramatic changes in tempo. The production is spacious and gently tweaked from tune to tune. But the music of Blackstar is about the words, and to understand its strength we have to make an effort to define what these last songs are “about.”

“Bowie” and “enigma” are frequently paired in reviews and on-line discussions (Google refers you to some 579,000 sites that use the two words together). But “enigma” seems like a flabby cop-out to me. Bowie had very specific things to say; if listeners could not always interpret his songs specifically, that wasn’t his fault.

And Blackstar is nothing if not specific.

Two of the songs could be from films about twisted relationships: “Sue (or In a Season of Crime),” with additional music credited to jazz composer Maria Schneider, is a noir in microcosm, with sacrifice, love, betrayal, and murder flashing by, not necessarily in that order. “’Tis a Pity She Was a Whore” juxtaposes the language of John Ford’s incest-murder-mutilation tragedy with contemporary tough talk (“Man, she punched me like a dude / ‘Hold your mad hands,’ I cried”), a montage of love as war.

Three of them are dramas of the alienated: “Lazarus,” written for Bowie’s theatrical collaboration with Enda Walsh, is a yearning-for-release monologue by Thomas Newton, the alien played by Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth. “Girl Loves Me” is a cri de coeur of a desperate young man, simultaneously in the now and in the future, using language from Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange. The title track is dire and vaguely martial, infused with ritual, violence, and protest (“On the day of execution / Only women kneel and smile . . . He trod on sacred ground / He cried aloud into the crowd . . . Take your passport and shoes . . .I’m a blackstar, I’m not a pop star, I’m not a gangstar [sic], I’m not a wandering star, I’m not a porn star, I’m not a white star . . . We were born upside down / I’m a starstar / Born the wrong way round”). Its images justify a report from Jody Rosen in Billboard that Bowie told Donny McCaslin its subject is ISIS.

And then there is the pair that close the album (“Dollar Days” and “I Can’t Give Everything Away”), meshed together with an overlapping segue, among the most beautiful and moving of all Bowie’s works, where he may be saying farewell in his personal way (“I’m falling down / It’s nothing to me . . . Don’t believe for just one second I’m forgetting you . . . Seeing more and feeling less / Saying no but meaning yes / This is all I ever meant / That’s the message that I sent / I can’t give everything away.”)

In these two songs, we also get a fine Ben Monder guitar spot, and two McCaslin tenor saxophone solos that perfectly demonstrate the quality that jazz people like to call “telling a story” – they are improvised statements that take you from point A to point B and leave you profoundly fulfilled.

McCaslin’s language on his horn is akin to Norbert Stein’s, although they hail from different post-Coltrane generations. McCaslin might be seen as part of the fourth generation, the one in which Michael Brecker was the central figure. As a soloist, Stein sounds like a third-generation player, spiritually related to Dave Liebman and Steve Grossman, with an agreeable slight vibrato that humanizes his timbre. As a composer, he has a firm foundation in Ornette Coleman, at least on his new release; three of the themes on Das Karussell are strongly Ornettish.

But, as with Blackstar, the music on Das Karussell: Norbert Stein Pata Messengers Play Rainer Maria Rilke is in service to the words, and Stein has taken a bold risk that pays off sensationally well. Instead of setting Rilke’s words to music in lieder or accompanying readings of them with musical color, he introduces each of the eight compositions on the CD with an unaccompanied reading of a poem by Ingrid Noemi Stein, a gifted young actress who reads the words with admirable clarity and grace. She never chooses the singsong that so many poets employ when reading their own words. Instead, she gives us a clean, elegant stream of voice that draws us into Rilke’s thinking and haunts the music that follows.

Stein describes the poems he chose for the project as being about “life, love, and passion,” but anyone who knows Rilke’s texts knows that they do not easily resolve themselves into straightforward themes. Example: the title poem, “Das Karussell” [The Carousel], is ostensibly a description of a merry-go-round in colorful whirl. But why does Rilke point – three times – to the occasional appearance of “ein weisser Elefant” [a white elephant] if not to suggest the persistence of mortality within the bustle of living? Why is one of the merry-go-round animals “ein böser roter Löwe” [an evil red lion] ridden by an anxious little boy? And why does the poem bitterly undercut its final image of a smile (“ein Lächeln . . . verschwendet an dieses atemlose blinde Spiel” [a smile . . . squandered on this breathless, blind game])? Clearly there are other games afoot on this carousel, and in the other poems as well, and the odds in these games are always in favor of the House of Death.

German is a language of umami – its sonic beauty is like the smell of mushrooms, or the crunch of dead leaves underfoot. It is not convivial like Italian or elegant like French or flamboyant like Spanish. Its relationship to English is primitive, even feral. The two languages, descendants of a common Teuton progenitor, share a dark camaraderie, occasionally starkly similar (“das Ende ist dort” [the end is there]) and often densely, mysteriously different (“Graue Liebesschlangen . . . verdauen Lust-Klumpen” [Gray love-snakes . . . digesting clumps of passion]). An English speaker with a smattering of German vocabulary can almost understand Rilke directly at one moment, but then the poet’s meaning slips away into a forest of unintelligible syllables.

Norbert Stein has thoughtfully provided English translations of the poems in the CD booklet, and a careful reading of them alongside Ingrid Noemi Stein’s narrations can free an English-speaking listener to hear the substance as he or she slides into the music.

Norbert Stein: as a composer, he has a firm foundation in Ornette Coleman. Photo: Petra Fischer.

However, the saxophonist does not compromise by giving us his most tuneful interpretation first. The leadoff, “Wie sol lich meine Seele halten” [How shall I hold my Soul], is a graceful love poem where Rilke tries to hold his soul apart from that of his beloved and finds it impossible. Stein’s theme may be a depiction of this struggle – angular, tense, without tonal center – which eventually transits into free improv.

Better for a first-time listener to begin with the third poem, three rather grotesque lines called “Graue Libesschlangen” [Gray Love-snakes]. Stein might have opted for something sinister or sinuous in the music. Instead, he emphasizes the Lust [passion] of the last line, giving the snakes an appealing in-tempo bounce, vaguely Latin, in a definite key.

So it goes through the CD. Listening to it becomes a process of embracing each Rilke poem and then unpacking Stein’s meditation on it. Love is the subject at the forefront for the most part, and it is usually a mystical kind of love, very unlike the tortured love in Bowie’s songs. But the two poets see eye-to-eye, at least twice.

“Ich fürchte so vor der Menschen Wört” [I am so frightened by the Words of Men] contains these lines, which Bowie himself could have written: “Die Dinge singen hor ich so gern / Ihr ruhrt sie an; sie sind starr und stumm” [I so love to hear things singing / [But] you touch them; they stiffen and grow still]. Stein’s music for this text has something in common with Bowie’s music for Blackstar, martial and intense, recalling Albert Ayler’s folk-like marches.

And “Freilich ist es seltsam, die Erde nicht mehr zu bewohnen” [It is truly strange to no longer inhabit the Earth] imagines regretfully leaving behind mortal trappings “dass man allmählich ein wenig Ewigkeit spürt” [before one gradually feels a little eternity], which isn’t very far from Bowie’s “I can’t give everything away.” In this case, Stein’s interpretation is through-composed without an improv section. The line is very affecting, lyrical and tuneful, with Etienne Nillesen providing a delicate underpinning of free drums, and then there is a surprise second melody that takes a turn towards Japan.

Guitarist Nicola Hein: he is pungent and plangent, a foil against which the other players sound traditional. Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The musical execution by Stein’s group, the Pata Messengers, is top-notch on every track. Guitarist Nicola Hein has a role here similar to Ben Monder’s on Bowie’s disc – he is pungent and plangent, a foil against which the other players sound traditional. In his solos, he draws from the whole post-bop guitar palette, from Wes Montgomery to Sonny Sharrock, and in “Das Karussell,” he goes beyond it, with the use of a bar on the strings for an effect much like Ornette Coleman’s violin playing. Drummer Etienne Nillesen has the discipline to follow some intricate composed lines and the stamina to open up to full-bore free playing when necessary. And bassist Joscha Oetz is a delight throughout, with a warm, woody tone in the ensembles and a sure touch for his solos.

The concrete has danced with the abstract in a swirl of variations throughout music history: sung words, spoken words, rhymes in rhythm, songs half-spoken, monotone chant, opera, museum installation, back-porch jam; from Gregorian chant to hip-hop, from campfire to minaret to Broadway to street. There are almost as many solutions to the words-and-music challenge as there are musicians on the planet. In these two releases, Bowie and Stein each advance the tradition significantly while strongly swimming against most contemporary currents. In each of their CDs, the words rule the music, but the music inflames the words. Each presents a distinctive and subtle approach to the hybridizing of poetry and music, and each calls the listener back for repeated hearings. They do not give us easy music, but the best music is never easy.

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

Tagged: Ben Monder, Blackstar, Das Karussell, David Bowie, Donny McCaslin, Nicola Hein, Norbert Stein, Pata label, Rainer Maria Rilke