Film Review: Acknowledging Jean Epstein — Brilliant Maverick Filmmaker and Critic

Jean Epstein’s body of work is full of pleasures, surprises, and the revelation that this vigorous director broke ground for filmmakers and cinematic movements to come.

Young Oceans of Cinema – The Films of Jean Epstein, at Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, MA, January 29 through March 5.

Director Jean Epstein — he energetically accepted the challenges of the young medium.

By Betsy Sherman

French director Jean Epstein has been seen, if at all, as a one-hit wonder. His deeply creepy, avant-garde silent Poe adaptation, The Fall of the House of Usher, is an art-house Halloween staple—and that’s been about all we’ve had. But thanks to recent restorations and interest in his theoretical writings, a healthy Epstein retrospective is making its way around world cinémathèques. It lands in the Boston area at Harvard Film Archive as Young Oceans of Cinema—The Films of Jean Epstein. Twenty-three films—fiction features, documentaries and shorts (plus a documentary about him)—will play between January 29 and March 5. Most will be shown on 35mm film, the better to show off their aesthetic riches.

What took so long?! This body of work is full of pleasures, surprises, and the revelation that this vigorous director broke ground for filmmakers and cinematic movements to come. Although the experimentation that made the 1928 Usher so special is emblematic of Epstein’s restless intellect, we learn from the series that he dipped into many genres, spoke to audiences from the narrowly highbrow to the broadly commercial, and that he was capable of moving from extreme artifice to total immersion in the natural world. In its entirety, his filmography is heterogeneous and impervious to labeling; on that score he brings to mind more recent directors who pinball between big and small productions, fiction and documentary, and from genre to genre, such as Steven Soderbergh and Wim Wenders.

Jean Epstein (1897-1953) was a French national born in Warsaw. He and younger sister Marie, who would become a screenwriter and assistant on some of his films, were raised in Switzerland. Their father wanted Jean to be an engineer. He avoided that profession by entering medical school, but gravitated towards the arts. First a poet, he was drawn to what was being called the seventh art: cinema. He proved willing to explore the challenges of the young medium.

Epstein’s first screen credit was on a documentary about Louis Pasteur. In short order, he was given a contract with Pathé. His 1923 feature debut, The Faithful Heart/Coeur fidèle, a love triangle set in Marseilles, made a big splash among French cinephiles. It plays on the series’ opening night at 9:30, preceded at 7 by 6 ½ x 11/Six et demi, onze and the short His Head/Sa tête. Both programs will be introduced by Sarah Keller, co-editor of Jean Epstein: Critical Essays and New Translations. Among the books Epstein wrote proffering his theories of filmmaking were the 1921 Bonjour, Cinéma, the 1946 The Intelligence of a Machine, and the 1947 The Devil’s Cinema.

Epstein’s evolution was swift; he developed a number of signature strategies for deepening the film experience. Close-ups were not exactly new, but Epstein made use of them more often than his contemporaries did and thus showed faith in his actors. He superimposed images, doubling and tripling the information supplied to viewers for an impressionistic effect. He believed that slow-motion filming had a special power, and that slowing down the gestures of an actor enhanced the audience’s ability to identify with the character. Subtle use of low-angle and high-angle shots helped elicit various emotions. Towards the end of his career, he manipulated sound in exciting ways. The subject of these latter experimentations was his great muse—as per the name of the series—the ocean.

Here’s a look at films from the series that were available for advance preview, in chronological order:

The Red Inn/L’auberge rouge (1923), while a serviceably constructed narrative uniting two locations and time periods, gives only a hint of the sophistication to come in Epstein’s work. An adaptation of Balzac, it is set at a 19th century dinner party that includes a young engaged couple and their elder relatives; the comfortable atmosphere is shattered by a story related by the boy’s father. The flashback action takes place at a crowded inn at which a murder happens, for which an innocent man is blamed. Evocative imagery includes horses’ hooves in mud (later rhymed by wooden shoes), buckets of rain, a blazing fireplace, a sinister tarot card reader, and a handful of diamonds displayed by a doomed jewel merchant that send an erotic charge throughout the room.

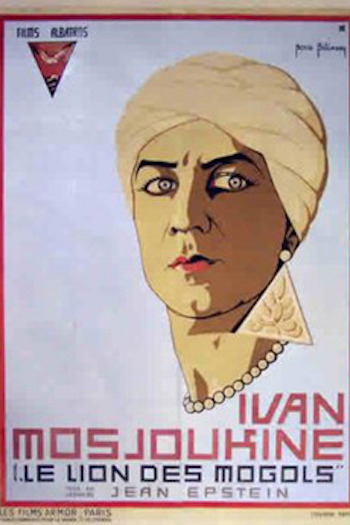

The Lion of the Moguls/Le lion des Mogols (1924) was the first of a series of very entertaining silent features Epstein made for Films Albatros, the studio set up by White Russians who had fled the Soviet revolution. In the guise of big, nutty escapism, The Lion of the Moguls actually has a kernel of realism, since it serves as a metaphor for the passage of its intense writer-star, actor-dancer Ivan Mosjoukine, and his colleagues from Kiev to Paris. The movie starts as a poorer relation to D.W. Griffith’s Babylon in Intolerance. With a mish-mash of exotica, it’s said to be Tibet—anyway, Mosjoukine’s costume shows off his great gams. He’s grand officer Roudgito-Sing, later to be known as the Prince. He’s forced to flee, and in a delightful twist we learn that this Tibet exists not a millennium ago, but during the 1920s. And the exiled Prince stumbles right onto a film set. Immediately smitten with the leading lady, Anna (played by Mosjoukine’s wife, Nathalia Lissenko), the Prince goes with the crew to Paris and becomes an actor to be near her. She’s the unhappy kept woman of the financier of her films. Although she and the Prince heave breasts over each other, and the young man’s hormones rage, Anna feels a restraint that she doesn’t quite understand. It’s a treat to see the making of the movie within the movie (there are always musicians playing off-camera to set the mood). A nightclub scene finds the drunken Prince amidst a swirl of imagery (dancers include Kiki of Montparnasse), but the high point is a frantic ride in a convertible during which the Prince stands up, relishing the speed, the whooshing scenery superimposed over his blissed-out face. In its era, this was a new way of presenting time and space. Even the movie’s poster, by Boris Bilinsky, packed a punch.

Double Love/Le double amour (1925) is calmer than its predecessor and allows Nathalia Lissenko to show more colors in her acting in the role of a countess who’s a fool for love. It marks the start of a great association between Epstein and set designer Pierre Kefer. In his silents, the director places his actors within spacious settings, using what seems to be deep focus. The milieu in this melodrama is swank, at least to begin with. Protagonist Laure bankrolls her younger lover’s gambling habit; she loses her fortune and money she has borrowed, which causes her disgrace. His father sends him to America and he leaves, not knowing Laure will bear their child. She rebuilds her life, becoming a cabaret singer. Her son inherits that pull towards the baccarat table, and is as lousy a player as his father, who eventually re-enters the picture. Epstein uses superimpositions, dissolves, and shoots in a variety of angles, the better to show the interplay between irony and tragedy. The young man’s hands become symbolic (“How they remind me of your father’s,” Laure says with alarm). Coincidentally, the hands of this actor—Pierre Batcheff—will soon become among the most famous in cinema history when ants emerge from their palms in Luis Bunuel’s 1929 Un chien andalou (Bunuel earned his first credit as production assistant on Epstein’s Mauprat).

The Adventures of Robert Macaire/Les aventures de Robert Macaire (1925) revels in the universal language silent film generated during its short lifetime. It’s so much fun that it’s surprising it isn’t better known. Epstein’s last film for Albatros is nearly three hours long, divided into five chapters (already there was nostalgia, here for the serials of the 1910s). Jean Angelo stars as the roving thief; he’s got the chiseled good looks of Jean Dujardin from The Artist. Funny-faced Alex Allin as his sidekick Bertrand is a hayseed Jerry Lewis, with hints of Buster Keaton and Harpo Marx. Their exploits, which take place in the early 1800s, find them progressing from genteel trampdom in landscapes out of a Constable painting to the elegance of a chateau, where they masquerade as nobles. Robert gets to romance the marquis’ daughter, Bertrand woos a saucy maid. It’s inevitable that the boys end up on their respective rumps, until a new scam comes along.

Mauprat (1926) was the first production for the director’s new company, Films Jean Epstein. An adaptation of a George Sand novel, it’s a less than compelling swashbuckler, save for the interesting ambiguity in gender characteristics. The heroine played by Sandra Milanowanoff is a sporty horsewoman. In the male lead and a supporting male role, respectively, are Nino Constantini and René Ferté, both delicate, pretty-faced slips of things whom Epstein cast in several films.

6 ½ x 11/Six et demi, onze (1927) announces a new phase in Epstein’s oeuvre: it’s a multi-layered psychological investigation that in retrospect seems like a fever dream of ultra-modern 1920s iconography (the characters include professional Charleston dancers!). After the death of their parents, Jérôme, a taciturn doctor, becomes like a father to the charming, wayward Jean. The younger man disappears from their Paris-area mansion and sets up house in a Riviera villa with a flapper named Marie. After a series of shattering events, Jérôme, contrary to his cautious nature, falls in love with the same woman. The working title of the film was A Kodak (the replacement title refers to a film format). A crucial plot point—what’s on the roll of film in Jean’s camera—is made possible by this new consumer product. But the feature is less about story than about the visual and temporal expression of physical sensation and mental agitation. It’s simply gorgeous.

A scene from “The Three-sided Mirror.”

The Three-sided Mirror/La glace à trois faces (1927) is a tour de force in the same manner as its predecessor, this time in just 38 minutes. In succession, each of three women of different types—a socialite, a flamboyant Russian sculptor (with a pet monkey!), and a modest “good girl”—talks to a friend about the man they love. It’s the same man, referred to as “He.” There are patterns galore in the sets and costumes, and amazing compositions, often presented in layers, befitting the title’s implication. The character of “He” personifies Epstein’s fetishization of motoring culture. Decked out in a flat cap, trench coat, and knickers, the diffident heartbreaker makes a thrilling, and apt, descent down the spiral ramp of a garage, with the camera mounted on the dashboard of the sportscar. The film brings to mind the fractured-psyche movies of the late ‘60s-early ‘70s.

The Fall of the House of Usher/La chute de la maison Usher (1928) brings Epstein back to period pieces and synthesizes what he’s learned from his previous experimentation. He combines the title story with Poe’s “The Oval Portrait,” and makes Roderick (Jean Debucourt) and Madeleine Usher (Marguerite Gance) a married couple (as in the latter story) rather than siblings. In their dusky chateau, Roderick obsessively labors over his painting of his beloved wife, knowing that each stroke saps life from the woman (the actress sits within the painting’s frame, licked by light from the fire). After she succumbs, Roderick is racked by fear and guilt that she may have been buried alive. Epstein oversees imaginative camerawork, with one camera operator dedicated to the slow-motion photography. Madeleine swoons in multiple images, her white veil billows dramatically. Strategies that we now take for granted, but were fresh then, are employed to make the audience partners in Roderick’s madness. There’s a feeling that everyone involved, in front of and behind the camera, was possessed.

After the intensity of shooting Usher, one door closed for Epstein and another opened. He didn’t even go to the Paris premiere; he left that chore to the film’s producer, Abel Gance (director of Napoleon). Epstein traveled to Brittany for a rest and change of scenery. The islands off that northwestern corner of France would be his base for the next decade. As his sister Marie later said in an interview, it gave Jean the chance to be “far from social and professional taboos.” Going against the grain of most filmmakers, Epstein moved from well-staffed productions with professional actors to shoestring-budget enterprises in rough natural settings using non-actors. This work was created years before, and likely influenced, Robert Flaherty’s Man of Aran.

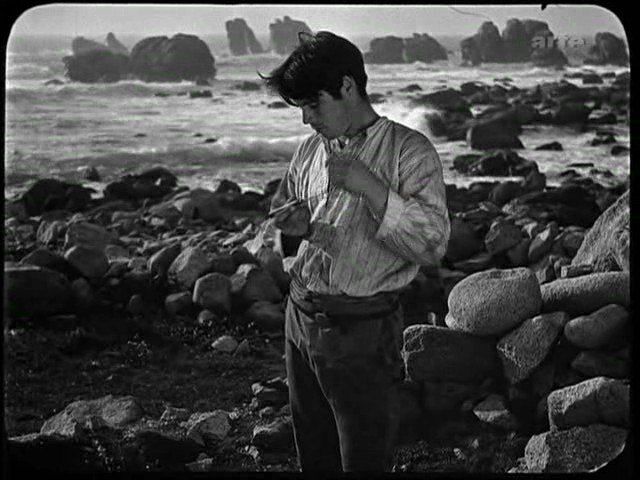

A scene from “Finis terrae” featuring Jean-Marie Laot.

End of the World/Finis terrae (1928) has the feel of a legend. It depicts a contemporary community, but one that lives a mostly pre-twentieth-century life. Epstein’s Breton films found the director-theorist in an unassuming position: he wanted to learn from the locals and use them to tell their own stories. But story is less important than the forces of the wind and the sea. The microcosm that starts off the film is a quartet of men, two around age 18, the others a generation older, who have left their island community for the summer to harvest seaweed on an even smaller island. There’s a semi-documentary explanation of their trade. In a curious scene, the boys share bread and wine but the bottle shatters. The boy who brought it explodes in anger, the other cuts his own thumb deliberately with the bread knife. The rift between the boys reverberates, its implications rippling from the tiny island to the bigger one (and perhaps beyond) as eventually the wound festers, threatening that boy’s life. On a sea that’s at first too calm for the sailboats, then too violent, one boat (with an elderly doctor aboard) travels toward the tiny island, another away from it. There’s a sense of push-pull, attraction and repulsion, like the tides—and a homoerotic undercurrent (Epstein was a gay).

Mor’Vran—The Sea of Crows/ Mor’Vran—Les mers des corbeaux (1930) is a documentary short with narration, marking Epstein’s entry into the sound film era. It conveys information about the island communities, sailors, and lighthouse keepers who would populate the director’s films for more than a decade. Inhabitants and film crew alike give due respect to the power of water and wind.

The Cradles/Les berceaux (1931) belongs to a genre that sprang up with synchronized sound film, the chanson filmée, forerunner to the music video, here with a tune by Gabriel Fauré. Sailors go off to sea, the women they leave behind rock babies to sleep, and worry. Epstein rhymes the wind rippling through grass with the rippling sea, and the structures of the ships with the peaked drapery of the cradles. Haunting.

Gold of the Seas/L’or des mers (1933) looks at the unromantic side of these claustrophobic island communities: small-mindedness and gossip run rampant. A drunken lout who bullies his teenage daughter finds a metal box that washes to shore and hides it. Word gets around that he’s found a fortune in gold, and everyone wants a piece. The neighbors wine and dine him; one man makes his son romance the girl, Soizic. This downtrodden, plain female blossoms in the warmth of his attention. Epstein has found a first-time actress with a light inside her; he films her in tight close-up as, overcome with emotion, she shyly smiles then covers her face with her hands. He even lets her glance, disarmingly, into the lens. Not everything goes well in this darkly comic tale, but an unforgettable face has been found (the film does not have credits for the actors). Epstein hated the overblown score that was given to the film by the distributor. Moreover, the short-lived Synchro-Ciné process of post-dubbed sound meant that the dialogue didn’t match the movements of the mouths. Still, it’s one of his most rewarding Breton films.

A scene from “Song of Armor/Chanson d’armor.”

Song of Armor/Chanson d’armor (1935) is affecting in its tale of happiness thwarted by discrimination and superstition. It was the first film made in the Breton language, commissioned by the newspaper Ouest-Éclair for the purpose of attracting tourism. This explains the abundance of dancers in traditional garb (think Gauguin’s Pont-Aven paintings). Yvon Le Mar’hadour stars as a wandering balladeer who sings about the travails of sailors and farmers; Epstein supplies the appropriate sea-and-landscapes. The singer is in love with a girl promised in marriage to a rich older man. The dramatic ending is breathtaking, although not exactly what you’d expect in a film promoting tourism.

The Woman from the End of the World/La femme du bout du monde a.k.a. L’île perdue (1937) was a film for hire, with not much to recommend it. Yes, there are mysterious forces afoot as a band of sailors, hired to bring a tycoon and a scientist to a tiny southern-hemisphere island on a search for radium, come in contact with an expatriate French woman who runs a roughhewn tavern. Wife to traumatized man and mother to a young son, she’s beyond reproach, yet she still becomes a femme fatale. She sings songs from home, and as the camera captures their rapt faces we can tell that each man uses her to fulfill a need in them, whether for a sweetheart, a mother or a symbol of La France. This production has neither the stimulating visuals of Epstein’s silent gems nor the authenticity of the semi-documentary works: it’s a conventional studio feature, with cheap-looking sets, and a cast of professional actors. Jean-Pierre Aumont is alright in the leading role of an officer, but more interesting are Germaine Rouer as the title character and Charles Vanel as the lowlife mechanic who resists the general adoration. There’s some substance here, but the vessel is wanting.

The war years were very hard for Jean and Marie (she later described their family as being “of Jewish origin”). They were able to avoid deportation by the Gestapo because of the help of friends and the Red Cross. As for Epstein’s previous work, the founder of the Cinémathèque française, Henri Langlois, not only saved the negatives of Epstein’s films from confiscation, he even showed some of these films during the Occupation, which took courage. Marie later became an important member of Langlois’ film preservation team. Jean returned to the islands of Brittany for his final two shorts celebrating the sea’s awesome power, the first fiction, the second documentary.

A scene from “The Storm Tamer.”

The Storm Tamer/Le tempestaire (1947) is Epstein’s final maritime masterpiece, this time letting mysticism dwarf realism. In spite of a bad omen, a young woman’s sailor boyfriend goes out to sea. She leaves her hearth in search of a legendary storm-tamer, who uses a glass sphere to calm the ocean. Along with the stylizing techniques of superimposition and slow-motion, Epstein manipulates the sound of the waves and wind, varying the speed and sometimes playing it backwards. As the director said, “if we can change time, an object becomes an event.”

The Fires of the Sea/Les feux de la mer (1948) was produced by the United Nations and celebrates the international network of lighthouses, essential to the shipping industry. Lighthouses and their guardians had figured in several of Epstein’s Breton tales. Their large, boldly patterned lights resemble a modernist art installation. Here, we learn the technology that makes the beacons function and, with the focus on a young second generation keeper, ponder the sacrifice required to live this solitary and dangerous life.

Jean Epstein, Young Oceans of Cinema (2011), directed by James Schneider, captures some of Epstein’s poetry while concentrating on his Breton period. The documentary includes a video interview with Marie and an audio clip of Jean. There are some astonishing shots with comparisons of rock formations now and when Epstein filmed them during the ‘30s—they haven’t shifted a bit.

May the works of nature and the works of this brilliant director endure.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Saw the first evening of this retrospective tonight at the Harvard Film Archive and I highly recommend what is to come to lovers of film — especially silent cinema. Jean Epstein is obviously a master … 1923’s The Faithful Heart is one of the finest silent melodramas (in the full D.W. Griffith mode) I have ever seen. Beautifully photographed and acted, with enough strange touches to keep you enthralled and/or scratching your head — for one thing, it features what must be one of the most depressed lovers in the history of film …