Poetry Review: “ask anyone” — Giving a Slant to Meaning

Ruth Lepson’s method in these poems is to encourage us to listen as carefully as she does.

ask anyone by Ruth Lepson. Pressed Wafer, 68 pages, $12.50.

By Allen Bramhall

Poetry is an argument consisting of syntax, sound, sense, and sensation. No, there’s no news in it. Poetry provides a place where we see language go somewhere, and we ride along with the human interest the words generate as they move along. Keep that elemental starting point in mind because it is key in appreciating the latest book by Boston area poet Ruth Lepson. Her poems embrace that argument, and they do so in a spare and modest way.

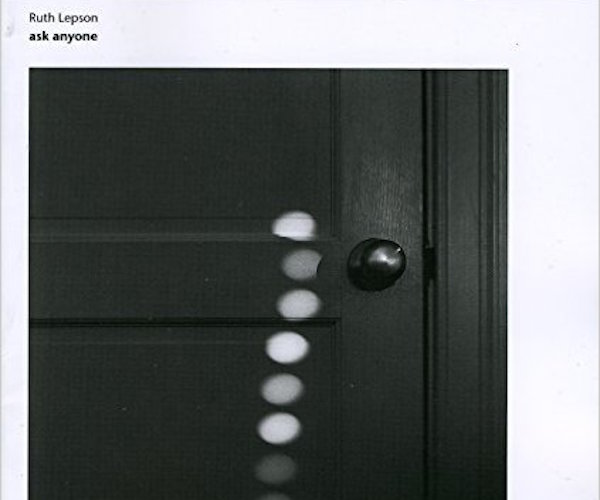

ask anyone seems like an exercise in reduction. Lepson’s poems intersect with small moments and particulars. The book’s design underscores that idea. It is a thin, white, squarish thing. The gray-scale cover photo shows circles of reflected light on a door — the magic of ordinariness. Author’s name and book title in tiniest practical font sit above the photo. The same tiny sans-serif font graces the pages within. Nothing splashy here.

Few poems listed in the table of contents range beyond one page. A couple of pages display three poems each. A considerable expanse of white surrounds the words. The poems mostly keep to a left-hand margin, though a number of them tab across the page, as well. The spacing is thoughtful.

One might construe the table of contents as either listing poem titles or first lines. Within the text, boldface seems to indicate poem titles, which only a few pieces have. This emphasis, however, does not appear in the table of contents. By leaving the question open as to whether the words should be understood as first lines or titles, Lepson is alluding to Robert Creeley’s masterwork Pieces. In that influential volume, Creeley used a single dot and a trio of dots to separate sections or fragments. Rather than making the linear-moving machines that we call poems, he broke through by creating a continuing poetic event that invites a certain amount of muddle, uncertainty about thought and its connection to words. Lepson works in a similar vein. Both question their articulation even as they exercise it.

Here is the first poem of Ask Anyone:

as

damaskask

anyoneit

was

beige

daythird

the

fourth

onecame saw

Relaxed to damask to ask: see how the vowel sounds generate words? I read the title as the first word of a phrase: relaxed as damask. Damask is often, but not always, a cloth made of silk or satin. It is no doubt pretty relaxed. The word derives from Damascus, and retains a poetic aura from its perhaps anachronistic use by poets such as Dante Rossetti. Polyester doesn’t have the same lyrical punch. Who says damask anymore?

The next lines defend that initial statement: “ask anyone.” If you have to insist that you are relaxed, chances are you aren’t. Creeley often delved into such quizzical (yet considered) ambivalence about meaning. It’s an act of assaying each word, each possible perspective.

The next four words—should we call the group a stanza?—require considerable puzzling out. To what does the impersonal pronoun apply? The mentioned damask, possibly. I don’t know specifically what the rest of the poem is getting at, but it is definitely reaching for something. Syntax has become fluid here, but I can feel expectation and perhaps regret in the poem’s combinations.

Here is a more syntactically available poem:

so she wouldn’t give me a ticket

which is totally insane

standing by the water fountain I said to myself

I’ll always remember this so I can

remember what fourth grade feels like

but all I remember is

standing by the water fountain

saying that to myself

I note two spaces between verses one and two, and one space between verses two and three. I infer from that a separation of incidents yet a similar dramatic tactic. The glibness of the phrase “totally insane” sounds casual, as if it was overheard in conversation. The child-like recollection of the other two verses likewise explores an idea about knowing the world, though in a hapless way.

Lepson’s method is to encourage us to listen as carefully as she does, which could well be another lesson from Creeley. His poetry springs from an intense musing on the ambiguities of sound and sense. Creeley practiced that “with [his] existential why,” as Lepson notes in her address to the poet, which closes this collection.

Like Creeley, Lepson is out to map subtle emotional territory. The following slightly cracked poem ends with a thump:

almost start crying

isn’t that funnyI was doing everything for you

I’m not really peeling

carrots now am I isn’t that

funny fuckhead

A sudden, very human, emotional shift occurs there. Lepson’s point isn’t to pin down an emotional state but just to see the words around it. Those are real carrots she isn’t really peeling, and the fuckhead probably was a fuckhead.

Lepson eschews punctuation with these works. Punctuation, especially the period, can be too definite because, well, poetry isn’t the news, it is not full of facts. Poetry is not about forming a definition but setting up the conditions for improbable linguistic connections. Without punctuation, words are free to fly about, to shape unexpected combinations in the reader’s mind. Lepson’s spacing, likewise, gives a slant to meaning.

One other poem to mention begins with a lovely line: “I wish you the bravery of the hummingbird who migrates over the / gulf of mexico.” Lepson doesn’t work with images often, but occasionally a warm picture pops up. A few lines further on in the poem she writes “may you see the diamond city on your way find time’s end.” I read that line humorously; as in, “Oh by the way, find time’s end.” Humorous, but wait a sec.

ask anyone is a book of quiet gestures and fleeting words. It is modest, as I noted earlier, though perhaps a better word would be unassuming. I think of Creeley, or Lorine Niedecker, among others, in the same way. And that reserve is valuable; Lepson’s book is not bombastic, the sinkhole which claims so much contemporary verse. She shows a subtle care for lines and enjambments; she knows that poetry should invite readers to ask questions, be confused, leap at ideas, and look around. I found myself doing those things and more on every page of Lepson’s ask anyone.

Note: Sound files of Ruth Lepson reading from ask anyone can be found here.

Allen Bramhall exists on the Internet with several blogs, and poems and reviews here and there. He has published a two-volume poem called “Days Poem” that was printed on paper by Meritage Press. He stands tall with the literati of Billerica, MA.

I believe if you talk about the cover photo for this book you should credit the photographer, no? This is a well known photo by Abelardo Morell. It was kind of spooky to see it in the article without attribution. (Because, it’s not a book design photo… if that makes sense.)

Other wise, thank you!

Thanks for the information. Author photos are credited (usually) but book cover photos are usually reproduced without credit to the photographer. At least that has been my experience …