Book Review: “Winter” — A Luminous Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man

This novel about Thomas Hardy becomes not only the story of an odd triangle, but also a meditation on the nature of art, where it comes from and how it comes to be made.

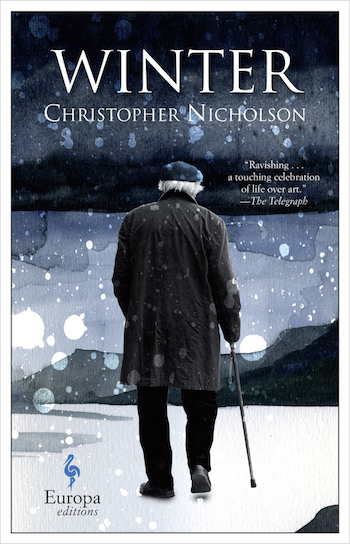

Winter by Christopher Nicholson. Europa Editions, 269 pages, $17.

By Roberta Silman

Thomas Hardy was a great English writer who lived from 1840 until 1928 and who is known to many Americans through the movies made of his novels Far From The Madding Crowd, The Mayor of Casterbridge, and Tess of the D’Ubervilles. These emphasize the setting — southwestern England, which in his novels is called Wessex — and the plot, which is always portentous, even when laced with humor, and usually very sad. For Fate with a capital F hangs over each of Hardy’s novels in ways that are uncanny and unforgettable. But the movies tell only part of the story, and I would urge anyone interested in the course of English literature to go back to these amazing books which were so influential as a bridge between the Victorians and later writers like D.H. Lawrence and E.M. Forster.

For Hardy, who came from very modest beginnings and was actually apprenticed as an architect before he started to write, has something to tell us even now, especially about women. He seems to understand headstrong and vibrant women like almost no other male writer and wrote about the constraints on their lives in ways that were revolutionary for his time.

That is why Winter by the English writer Christopher Nicholson is so interesting and compelling. In it Nicholson tells the story of Hardy’s 85th year, only three years before his death, when a play of his novel Tess is being given in Stinsford where he and his second wife Florence live — in the same house he designed years ago and where he lived with his first wife Emma. The role of Tess is being played by Gertrude Bugler, the granddaughter of the milkmaid whose beauty and sparkle inspired Hardy to write Tess so many years ago. And now, in his old age, he is mesmerized by the vitality and charm of this young woman; seeing her act has awakened desires in him that he thought had long died. Not only sexual desire, but also the desire to create more — this time in the form of poems. Although not known for his poetry when he was alive, Hardy’s poems are wonderful and their rich language has influenced people as different as Virginia Woolf and Robert Graves and Philip Larkin in later generations. Thus, this novel becomes not only the story of an odd triangle, but also a meditation on the nature of art, where it comes from and how it comes to be made.

Hardy was married twice: first to Emma from 1874 until her death in 1912, and then to his secretary Florence in 1914 until his death. He and Emma seemed to have been deeply in love, but became estranged for the last half of the marriage. No one seems to know why, but Nicholson does venture a guess that Emma wanted children when he was not ready for them and then refused to have sex with him when she became too old to bear children. Florence was his secretary and almost 40 years his junior when they married. But that marriage, too, was not very successful; he seemed haunted by his first wife and spent a lot of the time while married to Florence writing love poems to Emma. And there were no children to provide the usual pleasures and problems from offspring that can bring husband and wife closer. Only a faithful dog who in this novel is slyly named Wessex, called Wessie.

Against that background Nicholson’s novel gives us three points of view — Thomas, Florence, and Gertrude Bugler, the young actress — and he is so skillful that our perceptions of the situation change as we read. Yes, Thomas can be cruel to Florence. But from his point of view she deserves it because she is so unbelievably self-centered and hypochondriacal about a growth she has recently had removed from her neck. But then as she relays her disappointments, her claustrophobia as she lives her limited life in which her most important function seems to be to read to Thomas before they retire for bed to separate rooms, his insistence that they can’t cut down the trees shadowing the house because they, too, have feelings, our sympathies change. Maybe he is as muddled as she seems to be. And when we read from Gertie’s point of view, we become even more involved, hopeful and expectant that this young woman’s talents will be recognized, then dismayed and disappointed at the turn of events. In Nicholson’s capable hands Gertie’s story has a Hardy-like trajectory, and Gertie becomes, ironically, exactly the pawn that her ancestors and so many women of earlier generations became, simply because she is still a country girl, naive and cowed by a jealous, sometimes crazed older woman who has made her a scapegoat after years of frustration living with the “great writer.”

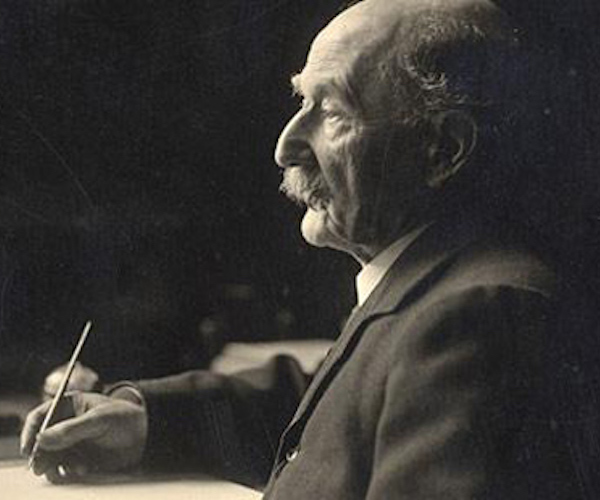

Thomas Hardy, pen in hand — Nicholson’s version of the old writer is so appealing, even when ornery, that we begin to feel that, at last, we really know him.

In the end, though, it is “the portrait of the artist as an old man,” as PW called it in a starred review, that grabs our attention. As Colm Tóibín disappears as we read The Master, his superb novel about Henry James, Nicholson vanishes as we read about Thomas Hardy in Winter. The old writer is so appealing, even when ornery, that we begin to feel that, at last, we really know him: his doubts, his disappointments (he was nominated for the Nobel Prize twelve times and was envious when Kipling got it), how he worked, his awareness of his shortcomings, his deep need to “shape reality,” his worries about how the work will be regarded after he is gone. Here he is asking that very question:

Which parts of his work would endure longest? That it would be his poetry he very much hoped; judged by the highest standards of art, his novels fell well short. … People saw them as stories of country life, which they were, but they were also stories about love and its deceptions. Love, not the country, had been his true subject. And women? … Women were more fascinating than men, it seemed to him. The clothes they wore, the way they did their hair, their scents and voices, their music….

And as the story progresses, Thomas seems able to move about in time with utmost ease, imagining sexual ecstasy with Emma years ago on a beach, and also his own funeral, in such detail that he seems to frighten himself.

Was he normal? he thought. Surely other men were like this? Yet he knew it was not so. Other men were not like him. Somehow by temperament and training, his sensibilities had tuned themselves to a different key. At the drop of a hat he could change perspectives; could fly back to his childhood and become the boy he once was, or slip into the part of some other person, dead or alive. Equally, without difficulty, he could become a tree or a bat, or a bird. One effect of that daily relocating of the self was to loosen the ties that held him in the here and now, and set him free in a space of airy imagining.

I don’t know a writer alive who will not relate to that brilliant phrase: “his sensibilities had tuned themselves to a different key.”

So, although Winter is not a page-turner in the conventional sense, it is a luminous book, with setting and characters worthy of Hardy himself, about the mysteries of creation, about how to live a reasonable life while making art, about the sacrifices demanded of those who live with a serious artist, about the fragility of the work, itself. And while we watch this story unfold in this cold season in Dorset, we are imbued with a kind of wintry happiness that only a wonderful book found in this season can bring. A perfect antidote for the weather now descending upon Boston.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Christopher Nicholson, Europa Editions, fiction, Thomas Hardy