Rock Remembrance: Prime David Bowie – Let’s Paint Our Faces and Dance

Before Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, before Iggy Pop, before the New York Dolls, David Bowie was my personal post-’60s music inamorata.

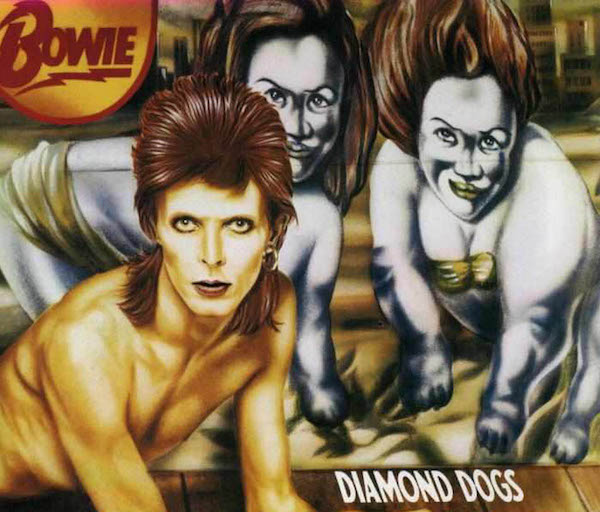

Guy Peellaert’s cover for David Bowie’s 1974 album “Diamond Dogs.”

By Milo Miles

Readers of my online writing of the last few years may believe I have a recurring obsession with the 1973 book Rock Dreams by Belgian artist Guy Peellaert and British journalist Nic Cohn. But my concern is really only the cover. The book’s initial printing featured five major rock icons at a ’50s diner counter: Elvis, Dylan, Lennon, Jagger, and Bowie. This was absolutely the sequence of succession for the Kings of Rock and Roll at the time (though there were problems: why all white guys? Does the Next Big Thing just have to come from England?). Rock Dreams was a hit but eventually went out of print. It returned a couple decades later with an outrageous alteration: Bowie had been chopped off the cover picture!

This may have been a crude reflection of a changed pop-culture consensus, but it was a dishonest re-write of pop history. The future belonged to David Bowie in 1973. Now he’s gone at age 69 and it seems 1973 was not a misperception but a more complex truth than anyone realized. Most important, Bowie’s prime moment deserves to be restored.

Before Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground, before Iggy Pop, before the New York Dolls, David Bowie was my personal post-‘60s music inamorata. Hunky Dory was a glorious, all-excitement album that was not an extension of the British Invasion or a distillation of any counterculture known. Like the finest rock releases, it contained knowledge of what sounded like all earlier music and then took a step beyond. Most tracks on the first side are outright forward thrusts about how outrage was hardly over and how flamboyance and theatrical beauty were new adventures. The track I single out nowadays, though, as the most purely David Bowie is “Life on Mars” – the poignant tale of a miserable, isolated adolescent girl escaping from her ugly home-life to the afternoon movies. Its message is how hard the reach for change and the future are going to be.

All it took was a little makeup back in the day, however. For the first time I painted my face for public consumption because Bowie clued me in how bumfuzzled people would be by the gesture. Bowie, with help from the Dolls, also convinced me to sport my only pair of high-heeled boots. Oh, and play Ziggy Stardust and (especially) Pin-Ups, no matter how much the stuck-in-the-muds howled. The release of Diamond Dogs with the Peellaert portrait of Bowie as a human-hound-hybrid (dick out and about, of course) is bound up in my mind with my first visit to Berkeley, CA and how hardcore hippie vets concluded Bowie had gone too far this time, man.

Would it be another re-write of history to claim Bowie was not subsumed by the rise of punk? His instincts stayed on-target in that he didn’t bother with punkishness; instead, he became the rock master, along with Blondie, who best engulfed and assimilated disco and the new dance modes of the later ‘70s. (His trouble with keeping up with these adaptations was my prime lesson in how unforgiving and challenging shifting dance languages are.) My choice from this era is a much more familiar and beloved number, “Heroes,” which I imagine spoke to a grown-up “Life on Mars” girl – the future remains hard, only a day long, but it is still there.

In another parallel with Lou Reed, the only time I had a chance to review high-profile David Bowie was also the time I found his work the least satisfactory. Both the album Never Let Me Down (1987) and the notorious Glass Spider Tour that followed were failures for the same reason: it wasn’t because they were too elaborate or over-produced – it was because they were juiceless, rote, the most dreary re-applied makeup of a career. At the time I surmised Bowie was tired of the rock-star treadmill. Now it sounds more like his instincts were starting to misfire. For so many years afterwards, whatever suggested bold reinventions, like Tin Machine, delivered exhausted wheezes.

It is a truth universally recognized that an old guy who paints his face is a clown. I would never feel David Bowie’s future again. Then a couple years ago, the miracle happened. In a dark movie theater, of course. In the most rollicking sequence of the film Frances Ha, Greta Gerwig swirls down a street in New York as Bowie exults “Modern Love” on the soundtrack.

Tears welled up in my eyes as my brain shouted “That’s it – That’s it!”

The “Life on Mars” girl was back again – and forever saved.

Milo Miles has reviewed world-music and American-roots music for “Fresh Air with Terry Gross” since 1989. He is a former music editor of The Boston Phoenix. Milo is a contributing writer for Rolling Stone magazine, and he also written about music for The Village Voice and The New York Times. His blog about pop culture and more is Miles To Go.

This is from the guy who wrote the following?

“Mr. Bowie provided that by being at once outrageous and shallow. His mercurial changes in style recalled Bob Dylan, but with Mr. Bowie, striking a controversial pose—bisexual extraterrestrial, Aryan soul man or gnomic avant-gardist—was often all there was. His talent was for forming a cunning pastiche of other artists’ innovations, and he showed little affinity for rock-and-roll.”

Yep, I wrote that. And I wrote the above tribute. I don’t think either contradict a complex, intense relationship to an artist. I do think making public remarks without using your whole name is cowardly.

STARDUST: The David Bowie Story. By Henry Edwards and Tony Zanetta. (McGraw-Hill, $17.95.) David Bowie first attracted attention in the early 70’s during a lull in pop music.

The idealism of the previous decade was a shambles, and young audiences were listening for a performer who embodied their self-conscious disillusion. Mr. Bowie provided that by being at once outrageous and shallow. His mercurial changes in style recalled Bob Dylan, but with Mr. Bowie, striking a controversial pose -bisexual extraterrestrial, Aryan soul man or gnomic avant-gardist – was often all there was. His talent was for forming a cunning pastiche of other artists’ innovations, and he showed little affinity for rock-and-roll. Henry Edwards and Tony Zanetta’s biography of Mr. Bowie offers reams of unfamiliar information, but too much of it is gossip – sexual escapades, publicity tricks, trendy club hopping. After 1970, Mr. Bowie joined forces with the lawyer and would-be promoter Tony Defries, something of a latter-day British P.cT. Barnum. The five years of close association between Mr. Bowie and Mr. Defries, during which Mr. Zanetta was president of MainMan Ltd., their management organization, receive twice as many pages as the following nine years, during which the performer made his most daring records and became a superstar. Mr. Edwards and Mr. Zanetta lavish their prose on the singer’s meetings with the rich and imperious, the antics of his brash but masochistic wife, Angela, and especially on the plights of acolytes who had outlived their usefulness and were about to be ”erased,” drummed out of the inner circle forever. A provocative argument could be made that Mr. Bowie was the perfect herald of a fashion-fixated era in popular culture, but this deeply cynical book merely asks readers to be fascinated by a rock singer’s remorseless, chameleonlike personality.