Fuse Book Review: Living With the Spenders—Surviving an Odd Childhood

One has to be impressed by memoirist Matthew Spender, who refuses to descend into resentment and anger or anything resembling self-pity despite a very strange childhood.

A House in St. John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents by Matthew Spender. Farrar Straus and Giroux, $28, 436 pages.

Cover photo of “A House in St. John’s Wood: In Search of My Parents.”

By Roberta Silamn

In his great short story, “First Love,” Ivan Turgenev plumbs the depths of feeling that occur when an adolescent discovers that the object of his affection is his father’s mistress. Every time I read it a shivery tingle goes down my spine, and I marvel at the way Turgenev leaves so much unsaid yet tells all. I thought of “First Love” a lot while reading Matthew Spender’s memoir of his parents, because his father Stephen Spender cast a shadow on the family even greater than the one cast in the Turgenev story. For Stephen did not have a mistress, he had a series of relationships with young men that seemed to run the gamut from platonic to erotic (there is a disturbing vagueness about all this) and which caused great pain to his second wife, Natasha, who was also Matthew’s mother.

Oddly, and in spite of a rather strange childhood in which those aforementioned young men clearly played a role and in which his mother had a very intense relationship with—of all people—Raymond Chandler, Matthew Spender is a sensible, engaging narrator of this family’s story and in many ways the most interesting character in it.

Although extremely evenhanded and loving, Matthew makes it clear that the Spenders had entered into a bargain unlike any other. In an attempt to explain how two people could live so long together under such circumstances (they were married from 1941 until Stephen’s death in 1995), he begins with a straightforward narrative of his father’s life before the marriage in which it was clear that Stephen marched to his own drum not only in sexual matters (he was bi-sexual and his early lovers were W.H. Auden—very briefly—Tony Hyndman, Muriel Gardiner, and his first wife, Inez Pearn, among others) but also in his insistence on freedom from authority of any kind. Although Stephen came from a fairly conventional family and got a good English education, he left Oxford before getting a degree. And although he wanted desperately to be a poet, he ended up as a journalist who was known more for his life than his work, for his insistence on a peculiar kind of “freedom” within marriage than for anything he actually wrote.

He went to Spain in the 1930s, joined the Communist Party and fought in the Fireman’s Brigade during the Second World War, became a journalist, first at Horizon with Cyril Connolly and then, later, after the war, at Encounter, which he edited for years without realizing it was funded in large part by the CIA. This gives you some idea of how he lived, not really in the real world, but in a place of his own illusions, and the book he is best known for, a memoir, is called, appropriately: World within World.

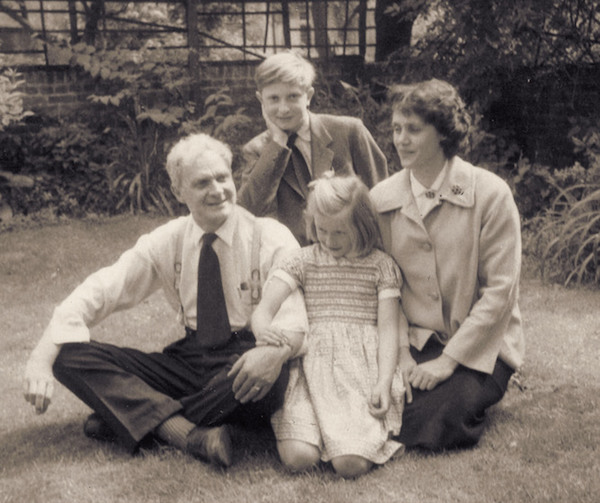

And then there is Natasha: the illegitimate child of Rachel Litvin who became pregnant by Edwin Evans, a well-known music critic who was married. Although Evans offered to divorce and marry her, Rachel chose the life of a single mother at a time when it was a lot harder than now—cf. Rebecca West. So Natasha remembered going “from pillar to post” while she was brought up, mostly by friends of Rachel’s, and became a fairly successful concert pianist. But in the context of her marriage she was pathologically attached to the conventional values and denied what was happening to such an extreme that, incredibly, she held the marriage together and inspired Matthew’s affection a lot of the time. How either parent fared with Lizzie, Matthew’s younger sister by four years, is unknown, because there is very little about her. In the only photo of her (also on the cover) she is looking down, unable to confront the camera. To give you an idea of how Matthew coped, here he is at 14:

I saw that they were both equally ambitious people, and that their differences were merely those of style. However, when it came to the emotions, it was clear that my mother was neglected. Dad’s attention lay elsewhere. He was an absent husband. If it came to that, he was an absent father. Behind his good manners there lay a detachment indistinguishable from boredom.

For six months I sided with my father, then for the next six months with my mother. Then one day I decided: this contest is not mine. It’s entirely theirs. I have no say in this matter. I must keep out of it. After all, for better or worse, the family works. Odd decision for someone so young but I never went back on it. The family would be OK; that was enough.

My decision denied our emotions, mine and theirs. I never realized until they were both dead, with their ashes next to each other in the same wooden casket I’d made for them with my own hands, how much their physical discontent had left them lonely.

From that clipped, matter-of-fact prose you can sense the resignation and disappointment and, yes, loneliness that Matthew endured while growing up while Stephen’s lovers, like the young Reynolds Price and later Nikos Stangos and David Plante and others, floated in and out of their lives. And while Natasha retreated into her own illusory existence, in which she was devoted to Chandler, could not acknowledge her husband’s sexual adventures, and insisted on his innocence in the Encounter affair. His mother’s refusal to face the truth, and her determination to keep the surface of their lives calm, may also be the clue as to why Matthew fell madly in love at 16 with young Maro Gorky, who was two years older.

Matthew Spender. Photo: Onform.

This memoir takes an important turn as soon as Maro enters the picture: the prose becomes looser, Matthew is less guarded, and although Maro never came up to snuff with either of his parents, especially Natasha, Matthew is clearly a happy young man. Maro is fascinating, talented, strong-willed, and also searching for the truth about her own parents, Arshile and Mougouch Gorky; most important, she is capable of giving Matthew the kind of love he has never known. He matures into a happy older man—he and Maro are still married and live in Tuscany where he is a sculptor and writer—and in many ways the second half of this book is even more interesting than the first.

Figures like Auden are still present. And there is the unraveling of the Encounter tangle. But these begin to take second place to the story of the Gorkys which becomes more and more vivid as we get to know Mougouch (Gorky’s nickname for his wife which means “mighty one” in Armenian), Maro’s beguiling and unconventional mother who becomes Natasha’s bete noire. They are all haunted by the memory of Arshile Gorky, who committed suicide when Maro was five years old and whose biography Matthew eventually writes. Somehow—in light of the Gorkys’ story and Arshile’s posthumous success—the narrative about the Spender parents pales somewhat.

Still, there are parallels between the two families that are complicated and interesting, and what matters most is that Matthew is able to let go and stop worrying about what either of his parents wants or expects from him. As he says:

Maro and I were both children of artists of talent, and we shared an intuitive idea of what was involved. There was the talent, and there was the world, and the two were connected in a mysterious way.

How Spender explores those mysteries as he matures is exhilarating to watch. Now the book is filled not so much with gossip about famous Brits but with insights and questions about family relationships that may appeal to a reader not particularly interested in British literary history. And throughout the whole of this book, one has to be impressed by its author who refuses to descend into resentment and anger or anything resembling self-pity despite a very odd childhood, and whose generous spirit informs the entire story in a unique and really quite wonderful way.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: A House in St John’s Wood, In Search of My Parents, Matthew Spender, memoir