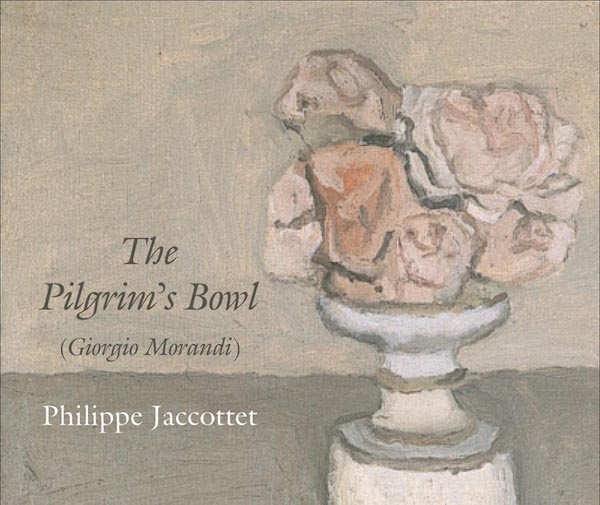

Book Review: “The Pilgrim’s Bowl” — Approaching the Enigma of Painter Giorgio Morandi

By Keith Payne

Beautifully produced by Seagull Books, The Pilgrim’s Bowl is a complementary and comprehensive introduction to both painter and poet.

The Pilgrim’s Bowl by Philippe Jaccottet. Translated by John Taylor. Seagull Books, 64 pages, $21.

Italian painter Giorgio Morandi has attracted the attention of, among others, Yves Bonnefoy, Federico Fellini, Don DeLillo, and Barack Obama. Scottish poet Ivor Cutler dedicated the following to him:

A chair,

And a table,

A man sits,

elbows on the table.

An eye in his head.

In the wall,

a window,

He sees

through the window.

His foot,

in a shoe,

rests on the floor.

A bird flits by.

The white wall

is matt.

Its texture

irritates the man

as he tries

in vain

to empty his head

to let a fresh thought

fill it.

As his teeth meet

they make a soft click,

like pebbles

in the water.

And it’s to this man with ‘his foot / in a shoe,’ that Swiss poet and essayist Philippe Jaccottet turns his eye as he skirts the studio floor and approaches, warily, the enigma of Giorgio Morandi.

Morandi was born and spent his entire life in Bologna and made his life’s work painting still lifes of bottles, flasks, and vases, “a group of his familiar objects.” Take a moment before following the lead of Jaccottet’s decisive prose to sit with Morandi’s paintings as you find them in The Pilgrim’s Bowl. Each of the 14 images is an inlay separate from the text; present, independent of all else, tactile and inviting you to touch, yet fragile, to be handled carefully. The inlays can be lifted up, and you will lift them up, if only to see what lies behind these enigmatic and utterly fascinating paintings.

It’s really as simple as a pot of tea, “the only sanity” according to Gwendolyn Brooks. Morandi’s painting of a teapot shows a solid object that’s very much there. Yet it quivers on the surface cloth. Present and solid and yet it could wash away at any minute, expunged like the tea it contains, the stained water poured from the pot. It is upright, proud, solid, simple, delicate, and firm. But there is so much the possibility of it not being so. Just like life. There, and just as quick not there. There, and almost not.

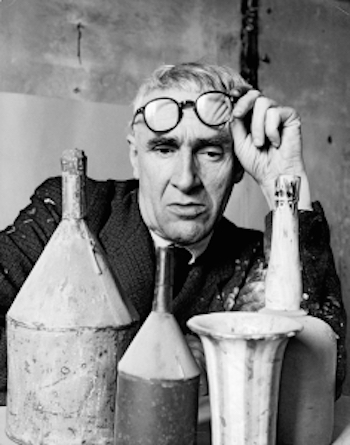

Painter Giorgio Morandi. Photo: Herbert List.

Jaccottet’s patience and “rigorous scepticism,” in the words of his translator John Taylor, enables him to approach Morandi with the necessary calm and clearheadedness. He does not decipher a particular painting; instead, he sidles alongside it, stands in its light, and tries not to cast a shadow: “The time has come to approach these paintings that made me unfaithful to a vow more than once confessed—not to write about art.”

But write he does. The Pilgrim’s Bowl is a series of essays and observations by Jaccottet on Morandi’s paintings, mostly still lifes, with a few introductory landscapes. The paintings segue into the text. They sit, sparsely affirming Jaccottet’s words, which rarely, if ever, refer to them directly.

The voices throughout the text, however, belong to more than just Jaccottet. There’s Italian poet philosopher Giacomo Leopardi and French philosopher Blaise Pascal, apparently among Morandi’s “favorite authors.” The painter himself is given space to speak and, holding all this together through his clear and attendant English, is poet and translator Taylor. It is as if the voices are layered over one another; at one point Jaccottet puts words into Morandi’s mouth: “one can imagine Morandi soliloquizing in the following way (or so we surmise, even knowing that he would have never have spoken in these terms).” It is as if they’ve all been mixed in the pilgrim’s bowl and, by osmosis, have come out in one voice speaking from behind the paintings.

But the question I ask myself is, who is holding this pilgrim’s bowl? From whose hand does it extend? And why a pilgrim’s bowl? Is it Jaccottet or is it Morandi? Perhaps we can say that Morandi shaped the bowl while Jaccottet carries it on a pilgrimage, extending the bowl to us, gracing us with a brief, passing glance inside what’s cupped in his hands.

Any discussion of Jaccottet must acknowledge the religious overtones of his writing, the spiritualism fed by Western Christianity and philosophy. Jaccottet’s poetry is ecstatic flight, the beat of the lyric pulse that enchants both reader and the poet himself into reverie. His cosmic dreams are simultaneously of the spirit and the Big Bang, whether he’s observing a cherry tree or a quince flower:

I sometimes think that the main reason why I continue to write is, or above all should be, to gather the more or less luminous and convincing fragments of a joy that—so it would be tempting to believe—exploded long ago inside us like an inner star, scattering its dust all around. Whenever a little of this dust twinkles in a gaze, this is probably what disturbs, enchants, or misleads us most; yet after careful consideration, this is less strange than to chance upon the sparkle, or a mere reflection of this fragmented sparkle, in nature. In any event, such reflections have initiated many of my reveries, not all of which have been entirely fruitless.

(‘The Cherry Tree,’ And, Nonetheless: Selected Prose and Poetry 1990–2009, Trans. John Taylor.)

Jaccottet’s aim is to generate enchantment, to translate glimpses of ‘fragmented sparkle’ into exaltation. Similar perhaps to Thomas Tranströmer or Derek Mahon, although Mahon, of the three, surges furthest from the Euro-Christian model in what David Constantine recently called his “Cosmos of Humanity.”

Jaccottet’s reverie, his lyric impulse, is constantly held in check (the “painstaking scrutiny” noted by Taylor). He is not content with flight alone, nor with the lazy sway of the easy answer, allowing for neither superfluity nor luxuriating in his own brief ecstasy. He quotes Jean-Christophe Bailly on Morandi: “…as if painting became a kind of tea ceremony, but for the eyes—an art of steeping the leaves of sensation in the water of detachment …,” only to upbraid him in the next breath with: “Permissible comparisons, if one does not dwell on them.”

Jaccottet also upbraids himself constantly throughout his poems. This is his “saving grace,” his ability to follow the lyric impulse, to run with it, but then to pull himself up and check exactly how far he has gone and why. And instead of entering the gates of heaven as it were, he chooses to stay—a pilgrim with his bowl—on his pilgrimage, revelling in Morandi’s work and his use of “the inevitable vases, jugs, and bottles”—through which “one experience[s] a sort of ascension, even an Assumption that seems real and in fact speaks to us only because it is no longer angel wings, nor the dance and laughter of any Matilda, that announce and prepare it.” As with Morandi’s paintings, Jaccottet’s poems often “tremble a little without ever drifting off in frailty or blurriness.”

Jaccottet, usually the poet of the conditional clause, of the perhaps, the maybe, the ‘what if’ of the discontented modernist, is unusually decisive in this volume. His decisiveness stems perhaps from speaking at one remove from his own sensory perceptions. He is also speaking from a “heroic concentration,” the “concentration in its pure state” he more than once applies to Morandi, but one that allows him to inhabit the space of the “almost everything” that is as much the almost nothing in Morandi’s case. And Morandi’s light casts no shadow. It is a presence and one that Jaccottet cannot beam himself onto, but must skirt the edges of the gallery, of the studio, of the painting, coming slantwise at the work as he approaches the enigma.

Note how he chooses enigma rather than mystery to describe his approach to Morandi. Enigma suggests something that can be solved, or at least worked on. Something that can be answered, or at least approached, given enough patience: “In the still lifes, colors are sometimes especially austere and winter-like—colors of wood and snow. They make you once again pronounce the word ‘patience’ and think of the patience of old farmers or a monk in his frock—the same silence as beneath the snow or between the whitewashed walls of a cell. The kind of patience meaning one has lived, toiled, ‘withstood’—with modesty, endurance, but without revolt, indifference, or despair; as if one nonetheless expected to be enriched by this patience, to the extent of believing that the patience would allow one to be silently impregnated with the only light that matters.”

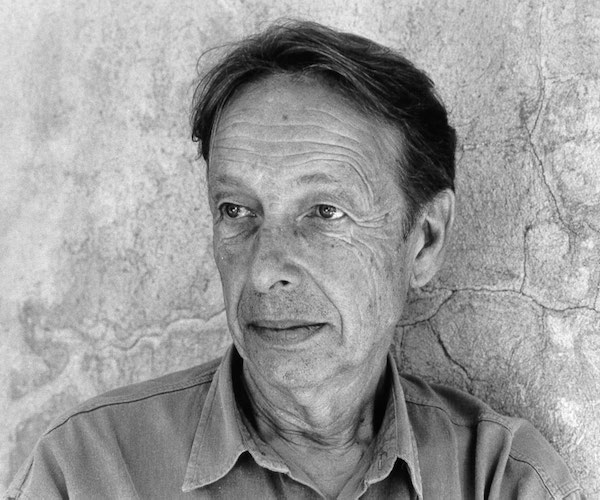

Poet Philippe Jaccottet—the modernist poet of the conditional clause, of the perhaps, the maybe, is unusually decisive in this volume.

The light that matters is ever present in Morandi, but it is a light whose source is not immediately discernable. Yet, like the revelation, it is always at hand. Commenting on Morandi’s description of Pascal, “With mathematics, with geometry, one can explain almost everything. Almost everything,” Jaccottet adds, “When I try to examine his painting, I must not forget these statements, nor that ‘Almost everything.”

And this is the space where both Jaccottet and Morandi can be understood. The “almost everything.” The almost everything that Jaccottet allows himself to be lost in while abroad on his lyric flights. The “almost everything” that Morandi reveals in the arrangement of “a group of his familiar objects,” that, for all their possibility and blurring at the edges of the vast expanse of being, are really no more than “a group of his familiar objects.” I am reminded here of Goya’s warning that “fantasy without reason only creates impossible monsters,” while “united with her is the mother of art and source of all your desires.”

“The enigma has to be approached from different angles, as naively as possible.” And this is how Jaccottet approaches Morandi, from various angles in the hope of finding a way into the ever-present light. This then, the space of the ‘almost everything,’ the space (in this case) held within the Pilgrim’s Bowl, is in the words of a similarly spiritual, skeptic contemporary of Jaccottet’s, the space ‘where the light gets in.’

Morandi’s still lifes are bare. As bare as his desert tones suggest, and as vast. There is no reference apart from the few assembled jugs and vases more often than not centred in the frame. To the sides, a vastness, which, while it lets the light in, casts no shadow. For Jaccottet, as for this viewer, on first looking at a Morandi painting there is an experience of strong emotions, a mix of whispered, quietened emotions, and then the astonishment that these emotions are inspired from the image of a simple bottle, vase, and jug. Yes, Jaccottet tells us: “I am not going to reproduce painted poems with written poems.” But there is more, “yet the other part of the task remains—trying to understand both the reasons behind and the meaning of this emotion (that is deep and lasting enough to be worth elucidating); trying to approach the enigma.”

And this is the space where Jaccottet realizes his art, where he finds Morandi, where they find each other. Beautifully produced by Seagull Books, The Pilgrim’s Bowl is a complementary and comprehensive introduction to both painter and poet. Under Morandi’s light, and within Jaccottet’s “almost everything,” we encounter both men. At the moment where in the full of life the life could be eclipsed. This too will end, Morandi tells us, to which Jaccottet replies, and yet while we’re still here…

Keith Payne is the Ireland Chair of Poetry Bursary Award winner for 2015. His debut collection Broken Hill was published by Lapwing Publications and Six Galician Poets, translations of contemporary Galician poetry, is due from Arc Publications in 2016. Keith lives in Vigo with the musician Su Garrido Pombo.

Tagged: Giorgio Morandi, John Taylor, Keith Payne, Philippe Jaccottet, Seagull Books, The Pilgrim's Bowl