Book Review: “Death by Water” — Imagination, Masterfully Redeemed

Death by Water plumbs the depths of the human condition in an entirely original way, in a way surprisingly accessible to a Western reader, in a way that is both evocative and provocative.

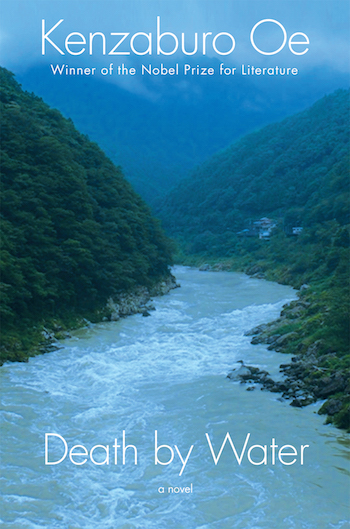

Death by Water by Kenzaburo Oe. Translated by Deborah Boliver Boehm, Grove Press, 424 pages, $28.

By Roberta Silman

I must admit that although I had certainly heard of Kenzaburo Oe and knew that he won the Nobel Prize in 1994, I had never read him until now. When his latest novel arrived I had no idea what pleasure it would bring, what worlds it would open up. For Oe is unique, a writer of exquisite nuance who—at least in this work—asks the most important question we face: How to live with as much dignity as possible? He also has an amazing gift of drawing the reader into his specific world as quickly and skillfully as possible, so that, before you know it, you are in a small town in Japan, smack in the midst of the family of his alter ego Kogito Choko who writes in the first person and is struggling with one of that family’s defining characteristics: a handicapped son. Most of the intimacy of the writing must be credited to Oe, but I would be remiss if I did not mention his very skilled translator, Deborah Boliver Boehm, whose grasp of the swings in Oe’s language—from magisterial to very colloquial—is surely worth noting.

In his marvelous essay on Proust, Vladimir Nabokov says that In Search of Lost Time is a “treasure hunt for the past.” So are a lot of great books, including some of Nabokov’s own novels. So is Death by Water. Its premise is that, at last, this well-known novelist who has reached his mid-70s (he is 80 now) will embark on a project to untangle the facts of his father’s death at the end of World War II in a bizarre drowning accident. To help him he will have the contents of a red leather trunk that has been kept from him by his sister because she was afraid that he would get the family into trouble if he wrote this story too soon. But now she has relented, he has access to the trunk, he has honed his craft since he was a young man, he has been honored all over the world, and he is finally ready to tackle this monumental task.

To do this he goes back to his hometown, where, coincidentally, the Caveman Theater Group is planning to dramatize various scenes from Kogito’s novels, including some from “the drowning novel” he has already written. Thus, Oe sets in motion this new novel with two simultaneous threads, which feed each other and keep us readers on our toes. There are Kogito, his wife and daughter and disabled son named Akari, there is his sister Asa, and their dead but still omnipresent mother and father. There is also Kogii, the name his family calls Kogito as a child as well as the name of his otherworldly playmate that he has as a child (sometimes they seem interchangeable). Then there are the members of the theater group, Masao Anai, its leader, and his right hand, Unaiko, her friend Ricchan,—all young and enthusiastic and inspiring to Kogito, especially when he becomes discouraged—and an old colleague of his father’s, Daio. All of them have complicated back stories that are revealed slowly as the novel proceeds.

Watching Kogito as he tries to fix his memory on the events of 1945 is fascinating, and we feel his anguish as he realizes what a slippery slope memory is: the more he tries to reconstruct the events around his father’s death, which may include his father’s involvement with an insurgent group bent on killing Emperor Mikado, the more confusing and insurmountable his task becomes.

Moreover, with the memories come the concerns about the future: his own death and what will happen to Akari after he is gone. Add to that a third thread which really takes hold almost halfway into the novel that involves Kogito’s complicated relationship with Akari, who cannot really function independently but lives for classical music—listening to it and composing it. With no warning this unusually patient and loving father loses his temper and calls Akari “an idiot,” thus creating a crisis within the family that undercuts all expectations about Akari’s future.

And then there are the references from T.S. Eliot, whose line from The Waste Land gives this book its title, from The Golden Bough, and other sources that nurtured not only Kogito but also his parents and the theater group. And letters from Asa about the work the Caveman Group is doing after Kogito has abandoned the drowning novel and returned to Tokyo. And discussions sprinkled throughout about what makes a story and/or a dramatization of a story compelling.

If it sounds like a dizzying mix, it is. And also one that no review should attempt to untangle. But, strangely and miraculously, because of Oe’s gifts, you become more and more curious as you read; the novel becomes more intense and urgent with each chapter until, finally, when he returns to the drowning novel, Oe begins to sort out events and conversations and impressions in a way that seems totally inevitable. Which leads to an ending that opens the book up into an entirely new area, yet connected to the question of what it means to be a parent: women’s rights and rape and abortion. This part of the book has more in common with a plot-driven crime novel than the one we have been reading. Yet it all works.

Kenzaburo Oe at the Japan Institute in Cologne, Germany. Photo: Hpschaefer.

Although it might help to have read Oe’s earlier books, I am not sure. I think each work is its own creation, e.g., Death by Water is, appropriately, given Oe’s age, filled with thoughts about aging and death. It is also about what an author leaves behind—not only the books, but the emotions and memories one inspires as a father and husband and colleague and friend. And where the connections to the past are. Here he is, discussing that:

It may sound paradoxical, but I think it is precisely the people who are trying to live in a way that’s detached from their own eras and from their contemporaries as well, who end up being most influenced by the spirit of the time they were born into. In my novels, I usually portray characters who exist in very private worlds, but even so, my ultimate goal is to somehow express the spirit of the era I’m writing about.

Oe has never denied that he writes autobiographically in his Kogito Choko books, and it is also clear that he is writing not only about how one makes a life but also how a novelist makes art out of that life. How his mind creates stories. Where dreams enter. How they are formed and how they sometimes provide ballast for events in fiction. The discussions he has with Daio in the last hundred pages of the novel turn out to be central to his method and are worth quoting. Here is Daio revealing an early discussion he had with Kogito’s mother:

Anyhow, I remember one time I said to her, ‘Kogito’s novels are pure fantasy, aren’t they? It’s amazing to me that he can exercise his imagination to such a degree and make things up out of whole cloth. When you come right down to it, I guess it’s simply a matter of talent.’

And then—maybe because she thought I was using some highfalutin-sounding words or something—your mother cut me down to size, snapping, ‘That isn’t fantasy; it’s just imagination.’ Then she went on to say, ‘My husband used to read the books of Kunio Yanagida, and he told me that according to Yanagida there is a clear difference between fantasy and imagination, because imagination has some basis in reality. So what Kogii’s doing is writing mostly about real things, which he augments by using his imagination. He has a very good memory for tales his grandmother and I used to tell him, and because he used folklore as a sort of launching pad for his imaginings, when we read his early books there wasn’t a single thing to make us think, Gee, this right here is some really far-fetched fantasy.’

In the citation for his Nobel Prize, Oe was praised for creating “an imagined world, where life and myth condense to form a disconcerting picture of the human predicament today.” Now, a little more than 20 years later, we have another novel—perhaps his last—which plumbs the depths of the human condition in an entirely original way, in a way surprisingly accessible to a Western reader, in a way that is both evocative and provocative. Raising questions that fiction should raise, but so modestly that we are intrigued rather than intimidated as we turn these pages. This is a superb book that should be read by anyone who is interested in modern fiction and what it can do when crafted by the right hands.

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Death by Water, Grove-Press, Japanese fiction, Kenzaburo Oe, nobel-prize-for-literature

A thoughtful review that makes me want to go out and get the book! I went through a phase of reading his work while a teenager and am thriled to read about this late novel. Thanks!