Visual Arts/Book Review: “Drawing in Silver and Gold” — the Miracle of Metalpoint

What seems to be a constant when contemplating metalpoint is an awareness of the constraints of the process, a feeling that it is miraculous that these works have come into being, and that they are unlike any other kind of drawing.

Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns, eds. Stacey Sell and Hugo Chapman. With contributions by Kimberly Schenck, John Oliver Hand, Giulia Bartrum, An Van Camp, Bruce Weber, Joanna Russell, Judith Rayner & Jenny Bescoby. Princeton University Press, 256 pages, $49.95.

By Susan de Sola Rodstein

Drawing is the creation of an image by a line flowing from a hand-held tool. We have come to think of drawing as perhaps the most common of artistic activities, starting in childhood, and as one of the most democratic, its materials easily available to most. Drawing also seems to us one of the most direct and intimate of art forms, an expression of personality as individual as its maker. Yet we have few surviving drawings that date from before the 15th century. Before the availability of affordable paper, drawings are thought to have been executed by perishable means or on reusable surfaces, such as chalk on walls, marks on wax tablets, or even a stick traced in earth; or made directly upon a panel, parchment, vellum, or wall to be painted over. Often, the consideration of drawing is subordinated to the study of painting, to which it is seen as hand-maiden.

The emergence of drawing as a complete and self-sufficient art, worthy of both collection and study, is implied in the ambitious historical reach of the exhibition Drawing in Silver and Gold: Leonardo to Jasper Johns, which opened at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. in May, and is now at the British Museum (through December 6). The exhibition and the beautifully illustrated catalogue, with essays by conservators and curators, focuses upon six centuries of metalpoint drawing, a little studied and still poorly understood medium.

Metalpoint is the art of drawing with a metal stylus or wire, most often silver, on a prepared ground. In its earliest era, vellum or paper was treated with a mixture of bone ash and animal glue to create a roughened “tooth,” against which a trail of abraded metal particles would leave a shimmering line. Goldpoint, seldom used because of its price, resisted oxidation, remaining light grey. Other metals would slowly oxidize to a range of tones, including greenish, yellowish, and purplish. Leadpoint, which quickly changes to grey, did not require a prepared ground and was more amenable to correction, but was prone to smudging, and the tip required sharpening. Silver and its alloys create a range of warm olive-browns, and even black when applied heavily. The vast majority of the works in the exhibition are silverpoint.

It is perhaps the single most demanding medium for drawing. Metalpoint is generally difficult—often impossible—to erase, and requires very sure draftsmanship. Its tonal range is limited. A stylus is of a uniform width and generally resistant to pressure. “Its shimmering line is simultaneously firm and delicate, appearing almost evanescent despite its clarity,” writes curator Stacey Sell. Effects of plasticity in drawings executed only in metalpoint (as opposed to mixed media metalpoint drawings) are achieved not by “stumping” or blending, but by the application of precise hatching strokes, sometimes so fine they are barely detectable by the human eye, as in Jan van Eyck’s “Portrait of a Man” (c. 1438).

Jan van Eyck, “Portrait of a Man (Niccolo Albergati?),” c. 1438.

Jan van Eyck, “Portrait of a Man (Niccolo Albergati?),” c.1438, detail.

Thought to be a portrait of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, this is our only surviving drawing attributed to van Eyck’s hand. It is also unique in combining layers of three different metalpoints: silver, silver-copper alloy, and goldpoint. The purpose of including goldpoint, according to John Oliver Hand, is still unclear, although one might guess that it might have something to do with goldpoint’s resistance to color-change. Delicate in execution, it is remarkable in the vividness of the likeness it conveys. Comparing it to the painting of Albergati, one has the impression that the drawing is more true to life. The detailed characterization achieved with the effects of incredibly fine hatching lines and play of light is somehow more authentic than the color-saturated painting, modulated to a dignified presentation.

Part of what is miraculous about metalpoint drawings is not simply their sheer beauty, their soft radiance and clarity, but their survival. Even in its intermittent periods of use, metalpoint, perhaps because of its difficulty, was never a common medium. According to Sell, some works of exceptional delicacy and detail have been misattributed as metalpoint. Even with contemporary imaging techniques, the materials of certain drawings, some from as late as the 19th century, remains unclear. Metalpoint’s origins are mysterious, although it has affinities with the use of a stylus (often a “blind” stylus that leaves no trace) in the making of medieval illuminated manuscripts, and with writing. Its relation to the arts of engraving and print-making, with which it would seem to have affinities, is also not yet understood. Dürer seems to have learned the art from his goldsmith father, who would have been familiar with working with a stylus. Yet, the possible relation between metalpoint-drawing and other forms of metalwork is also unknown.

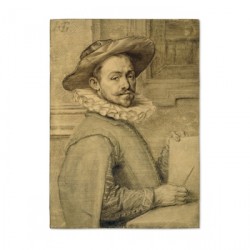

Hendrick Goltzius, “Self-Portrait Wearing a Hat and a Wide Ruff, Holding a Copperplate and a Burin,”c. 1589.

Most of the early examples of metalpoint drawings in this exhibition coincide with the Renaissance. And yet the period of its greatest efflorescence, leaving us masterpieces by Leonardo, Raphael, Dürer and Holbein among others, was also its seeming end. By the middle of the 16th century, metalpoint was in general obsolescence.

In his influential manual, c. 1400, “Il Libro dell’Arte” (Treatise on Painting),” Cennino Cennini advised pupils to practice with a metal stylus for two years on reusable vellum tablets or panels to avoid wasting costly paper. Yet it was metalpoint drawing’s durability and resistance to smudging, despite repeated handling, that also made it valuable for workshop use both in parts of the Italian peninsula, particularly Florence, and in northern Europe. Many of the examples in this exhibition are disassembled sketch book pages and workshop models. They were used for teaching, for storing and displaying stock motifs and figures, and as meticulous copy-records of completed paintings. Sometimes they may be identified as studies for specific paintings. In Italy, they were often executed on colored paper, and in both regions sometimes augmented with chalk, ink, washes and white highlighting. In the Netherlands, artists would sometimes score the paper to produce light effects. A focus on the finished product suggests that some may have been presentation drawings.

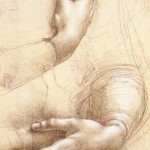

In general, metalpoint drawings tend to be small in focus and were seldom used for the composition of larger scenes, but more often for detailed human faces, and studies of elements such as hands, as in Leonardo’s eloquent “Studies of Hands”(ca. 1489/90). (This perhaps has its modern counterpart in Bruce Nauman’s “Some Illusions” series (2013).) We also have drawings of animals in various postures, such as Pisanello’s “Two Monkeys” and “Horses” (ca. 1445/1455), viewed from different angles.

Yet, according to curator Hugo Chapman, we have no Italian metalpoint drawings that date after the death of Raphael in 1520, a sudden cessation that remains as mysterious as the origins of the medium. We also have few works from Germany and Switzerland after 1550. Giulia Bartrum’s nuanced survey reveals examples of remaining practice in these regions. Its total absence in Europe in the 18th century (apart from a single known 18th century Swiss artist in Dresden, Anton Graff, who made miniature portraits), is puzzling, given the period’s interest in classical models as well as its embrace of restrictions. The absence is noted but not explored in the volume.

Rembrandt van Rijn, “Portrait of Saskia van Uylenburgh,” 1633.

It is sometimes speculated that metalpoint faded in importance with a shift in painting systems from linear, quick drying tempera, which, like metalpoint, required exactitude, to slow-drying oils, which permitted improvisation and revision, and used techniques of blending. The gestural and friable qualities of ink and chalk would seem better suited to this system. Yet, as Chapman points out, metalpoint persisted longer, if sporadically, in northern Europe, where oil painting had been invented. The premium on exact replication and on craftsmanship, as opposed to invention, must have played a role in its greater longevity in the north. It appears in the Netherlands as late as the 17th century. An Van Camp asserts, “silverpoint was exclusively utilized in the studio” in Italy, whereas in regions of the present-day Netherlands, Belgium and Germany it came to be used outside the studio, for sketching, outdoor drawing, portraits and exercises. It also played an increasing, if unclear, role in printmaking, where detailed studies were useful.

Its portability also recommended it for use in the private domain. Spill-proof, with no need of sharpening, metalpoint was used outside the workshop for sketchbooks and close studies of landscape and loved ones, favored subjects in post-Reformation Holland. The remarkable and sought-after meticulous silverpoint portraits by Goltzius and his pupil de Gheyn II in the later 16th century are among their “most admired works.” Where Goltzius learned the art is unclear, as his first silverpoints appeared “nearly fifty years after the last known metalpoint drawing in the Netherlands of 1527.”

In the works of Bol, Wierix, de Passe, von Tilborgh, and Both, Van Camp makes convincing arguments for a longer and more widespread practice than previously thought. As late as 1633, Rembrandt used silverpoint to make a memorable and loving portrait of his fiancée Saskia, and to make sketches in a notebook on a trip to Friesland, using both ends of the stylus, adapting the medium to his own “loose manner of drawing.” One wonders what may have prompted Rembrandt to take up, albeit briefly, a medium that had been largely out of fashion for one hundred years? A number of the 16th and 17th, Flemish and German artists Van Camp describes seem to have been influenced by Dürer, and perhaps Rembrandt’s private experiment also had to do with a consciousness of its precedents, especially in drawings by Lucas van Leyden.

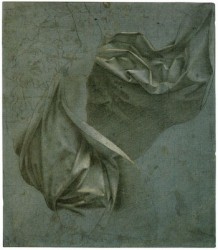

Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, “Study for a Drapery for the Risen Christ,” c.1491.

Perhaps because of its rarity, metalpoint seems always to reference a preceding era. “No other drawing medium is so closely linked with the Renaissance or so strongly compels artists to recall the draftsmen who used it centuries earlier,” writes Sell. The 19th century resurgence of interest in the Renaissance in England motivated artists such as Burne-Jones and Holman Hunt. Burne-Jones, working before the commercial availability of silverpoint materials later in the century, drew his classical figure-study “Antonia,” for “The Golden Stairs,” with a sharpened silver sixpence. Holman Hunt chose silverpoint for his lush and extravagant Pre-Raphaelite “Pearl,” knowing it would also be printed as a book illustration. A committed student of traditional techniques and materials, he chose silverpoint because it would be clearer than graphite but “softer than ink.” In more recent times, Joseph Stella and Jasper Johns have cited their engagement with Renaissance masters. Looking at Leo Dee’s nearly photo-realistic silverpoint of a torn envelope, “Paper Landscape” (1972), one cannot help being reminded of Boltraffio’s “Study for a Drapery of the Risen Christ” (c.1491). The association with the Renaissance is such a prominent aspect of metalpoint that Otto Dix, when charged with degeneracy by the Nazis, could make an implicit claim of lineage from Dürer with his copious silverpoint work.

Chapman raises the emergent Renaissance concept of “disegno,” the Italian word for a drawing that “also encompasses the mental formulation of the design prior to its physical realization.” Metalpoint was eminently suited to disegno, “as it demanded careful calculation how to realize an artistic conception within its strictures.” Since every mark of the stylus is usually indelible, it is not a medium for trial and error. One might further say that the hand—the artisanal aspect of drawing—must be in perfect subordination to what the mind has conceived.

Leo Dee, “Paper Landscape,” c. 1972.

In the hands of the most talented artists, metalpoint could also be used in a seemingly improvisational manner. Leonardo used elaborate metalpoint to produce the astonishingly controlled and imposing “Bust of a Warrior,” but he could also produce bravura loose sketches of hands in motion, cats cleaning themselves in inelegant postures in “Two Studies of a Cat and One of a Dog” (c.1475/80), and the “restless, kinetic energy” of the surprising leadpoint, “Madonna and Child with a Cat” (c.1480). For Leonardo, drawing seems an essential part of his thinking; at the center of how he investigated the world. Drawing was not just an artisan’s tool, but disegno, a central, if not the most central, liberal art. As the stature of the individual artist started to rise, drawing became a more distinctive activity, and drawings started to become objects to be valued, purchased, and collected. Vasari included a number of silverpoints in his art historical Libro de’ Disegni (Book of Drawings), “in spite of his belonging to a generation of Florentine artists who had largely abandoned the medium,” writes Chapman.

And yet, what did the specific use of metalpoint mean to its Renaissance practitioners? Were these artists, in turn, referencing the classical models and precedents they prized? We have no surviving drawings from antiquity, but metalpoint, an act of incision, and focused upon contour, would seem to have affinities with antique sculptures. The “Roman Nude and Horses,” attributed to Gozzoli, evokes the colossal Horse Tamers in Rome. Thea Burns, in her study, The Luminous Trace, has speculated that other antique incised forms, such as coins, vases, stone tablets, and metal artifacts may have also influenced these artists. She suggests that in choosing to use metalpoint, despite the variety of easier and more flexible media available to them, they were using a form that reflected how antique drawing was imagined. Further, that they were thus entering a humanist conversation—in sympathy with the perceived artistic value in rediscovered ancient sources—which also enhanced their own evolving status.

Leonardo da Vinci, “A Bust of a Warrior,” c.1475/1480.

We are so accustomed to valuing art as the emanation of an artist’s unique sensibility, it is hard to imagine the earlier status of the artist as an artisan, for whom drawing was first and foremost a skill to be mastered, a tool in the service of a craft. But it is perhaps possible to take the triumphalist Humanist interpretation of metalpoint too far, as the medium barely figures in Renaissance art after the first part of the 16th century. One could see the relative wealth of drawings we have in terms of technology—as a result of the existing metalpoint method of drawing coming into conjunction with the increased availability of paper. Analogously, its decline by the mid-16th century may be the result of yet more plentiful supplies of relatively cheaper paper and increased supplies of graphite. This availability, alongside the changes in painting techniques and the diminution of the workshop system, meant that drawings could not only be more improvisatory, but also no longer needed to be so durable.

Centuries after Cennini’s advice, and the transition from the training of artists in workshops to schooling in liberal academies, the challenges of metalpoint continued to suit it to pedagogical purposes. Charles Norton Eliot, the first professor of art history at Harvard in 1875 (of whom it is said that for him art history ended in 1600), together with Charles Herbert Moore, made the Old Masters the core of the curriculum, and also encouraged the practical study of Renaissance techniques. Alphonse Legros, an influential teacher at the Slade in 1880s London, venerated Italian masters and established metalpoint as a fundamental aspect of pedagogy: drawing as contour, and exclusive use of line to achieve volume, with no “lazy fudging.” It is reported that he put a student’s stump (blending tool) in a locker and threw away the key.

One of his students, Charles P. Sainton, promoted his work by publicizing, in highly dramatic (and entertaining) terms, his harrowing and heroic encounters with the challenges of silverpoint. Sell cites a journalist of the time:

“…he fears by a false irreparable stroke to spoil it all…absolute and undisturbed quiet, and even artificial means of steadying hand and nerve, must be adopted lest failure should ensue. He claimed to have held his breath while working, ‘for the slightest tremble would spoil the whole drawing.'”

Sainton was so successful in self-promotion, that, paradoxically, his ethereal drawings of fairies and ballerinas encouraged the idea that silverpoint, despite its difficulty, was a suitable amateur pursuit for ladies and young girls. At the end of the 19th century, there were “how to” instructions in the Girls’ Own Paper, which described it as “the fairy queen of the graphic arts.” Winsor and Newton began to manufacture silverpoint kits. The renewed interest in England may have also sparked a late 19th century revival in the United States, where it continues to attract modern artists.

Leonardo da Vinci, “Studies of Hands,” c. 1489/90.

In his discussion of Renaissance Italy, Chapman makes an analogy between the rigors and fruitful constraints of metalpoint and that of form (meter and rhyme) in poetry, likening its pursuit to a poet who chooses to write in sonnets. (A telling analogy, except that poets have the leisure to revise). Metalpoint continues to attract artists who embrace restriction and its rewards. Joseph Stella, for example, who revered and studied intensely the 15th and 16th century masters, did not copy them, but adopted the technique for his own subjects. He was attracted by the “unbending inexorable silverpoint”:

“In order to avoid careless facility, I dig my roots stubbornly in the crude untaught line buried in the living flesh of the primitives, a line whose purity pours out and flows so surely in the transparency of sunny clarity…I dedicate my ardent wish to draw with all the precision possible, using the inflexible media of silverpoint and goldpoint that reveal instantly the clearest graphic eloquence.”

In their elusive combination of delicacy and warmth, metalpoint drawings, whether photo-realistic, ethereal, or abstract, seem to argue for their own status as art objects, not only by the intrinsic allure of their metals, but through the rigors of their making.

In a world of instant images and deletions, where magnification often reduces all to pixels, metalpoint seems to attract artists in search of absolute and precise marks. And while much modern art has tended to bigger and bigger works, most metalpoint drawings remain rather small in scale (with certain exceptions, such as Fran Siegal’s wall-size studies for her installations). The range of metals used has widened to include brass, pewter, steel, copper, and even pure platinum, and the range of implements and grounds, some commercially prepared, has also expanded. Bruce Weber, who in 1985 curated the most extensive exhibition of silverpoint in the United States, discusses a number of artists currently working in metalpoint, including performance artists, who seem to make manifest the emotional valencies of their precious materials.

Carol Prusa, “Delphys,” (2010).

Susan Schwalb, one of the foremost of these contemporary artists, found metalpoint when she was looking for a medium with greater “precision” than graphite. Best known for her “Strata” series, shimmering landscapes made by an arduous process of sanding layers of diverse metals, she has expanded the range of materials and tools, using spoons, metallic pads, and even smoke. Although it is often abstract, there is warmth and earthiness to her work. Similarly, Carol Prusa’s painstakingly realized acrylic hemispheres, covered with hand-drawn silverpoint patterns, often inspired by nature and the cosmos, are a modern version of astonishingly assured draftsmanship. Her spheres, sometimes threaded with twinkling LED lights, seem to have both a futuristic and a humanist reference.

What seems to be a constant when contemplating metalpoint is an awareness of the constraints of the process, a feeling that it is miraculous that these works have come into being, and that they are unlike any other kind of drawing. One of the oldest works included, surely made at the youngest age, is a masterful goldpoint self-portrait by Dürer executed at the age of 13, “Self-Portrait at the Age of Thirteen”(1484). One wonders, finally, how self-conscious these early artists were about working with precious metals, and how aware of the aura of alchemy that attracts us to these materials still? How wondrous is the reverse alchemy, whereby metal is transformed into light-filled images of the highest order. It is our good fortune to have this exhibition, and this book, to bring them together across the centuries for the first time.

Susan de Sola Rodstein holds a Ph.D. in English and American literature from The Johns Hopkins University. As Susan de Sola, her poems have appeared in The Hudson Review, The Hopkins Review, Measure, River Styx, and Ambit, among many other venues. A David Reid Poetry Translation Prize winner, she lives near Amsterdam with her family.