Classical Music CD Reviews: Vadym Kholodenko plays Grieg and Saint-Saëns and Javier Perianes plays Grieg

Pianist Vadym Kholodenko is happiest when he shows off his chops without having to worry about coordinating with the orchestra. Javier Perianes is a musician of sweeping, Romantic sensibilities, eager to take a stand, and the result is a triumphant recording.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Vadym Kholodenko won the 2013 Van Cliburn Competition with bravura demonstrations of technique and some compositional ability. His cadenza to Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 21, which he wrote (always a good sign in a performer) and played during the Competition, was hailed at the time as a smartly-crafted, engaging contribution to the proceedings and suggested a musician of serious talent.

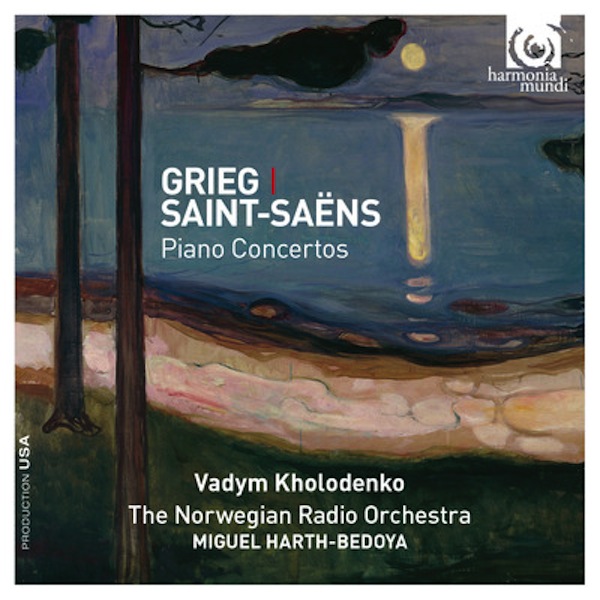

I was underwhelmed, though, by his HM debut album, which consisted of a muscular performance of Stravinsky’s Trois Mouvements de Pétrouchka paired with a superficial reading of Liszt’s (admittedly not-too-deep) Transcendental Etudes. Now, a year or so later, comes Kholodenko’s traversal of the Grieg Piano Concerto in A minor paired with Camille Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto no. 2.

Technically, the playing is confident and accomplished. Both pieces (especially the Grieg) feature fistfuls of notes and Kholodenko surmounts all the physical challenges they present with ease. He’s not all brawn: his light touch is nowhere put to better use than in the first movement of the Saint-Saëns, whose ethereal climax is the disc’s highlight. There’s some fine, poetic playing, too, throughout the Grieg, especially in the finale, where Kholodenko seems to be most at ease.

But both concertos are marked by the sense that Kholodenko’s happiest when he can show off his chops without having to worry about coordinating with the orchestra: the extended solo sections and cadenzas in each receive the most focused, insightful, and brilliant playing on the disc. When he’s being accompanied, his playing becomes more literal and fails to sing as freely as it should.

This tendency is demonstrated from the get-go in the Grieg. The opening movement’s first theme (after the famous cadenza) is articulated sharply, but it doesn’t really breathe. The busy animato transition that leads to the movement’s lovely second theme is played crisply and precisely, but lacks impishness and personality. Kholodenko’s playing is, on the whole, smooth and well voiced, but it’s curiously faceless, not overly concerned with highlighting or illuminating any corners of the score that might be of particular interest.

And so it goes. The second movement is lush and warm-toned, though its many 64th-note passages have a foursquare quality to them. Only the finale really works well, when Kholodenko seems to relax and have some fun with the music. The jaunty opening theme has a nice kick and the second theme comes across winningly.

He does well with the downright dreamy first movement of the Saint-Saëns, too. But he seems thrown for a loop by the succeeding ones. The sprightly second starts off well enough but gets bogged down by the middle; his performance is rhythmically indecisive and lacks momentum.

The finale also gets off on the right foot, though it, also, soon loses energy. On the whole, Kholodenko again approaches the music too smoothly and straightforwardly; he seems averse to taking any sort of risk despite (or maybe because of) its familiarity: the long section of trilled notes in the middle of the finale, for instance, needs to be much more varied than it is here if it’s really going to come to life. That said, the reprise of the opening material is lively and the coda genuinely exciting. But the whole performance doesn’t quite add up to more than the sum of its parts.

Miguel Harth-Bedoya and the Norwegian Radio Orchestra are Kholodenko’s at times inspired accompanists. In the Grieg, the second movement opens with luxurious tone and real depth of feeling and the finale includes some fine displays of tonal variety (the sul ponticello playing in the strings mid-movement comes out strongly). The first movement of the Saint-Saëns features a consistently lovely balance between soloist and orchestra. But at other points the playing’s workaday. The ensemble is occasionally untidy in the Grieg and the second movement of the Saint-Saëns sounds tentative and weak in spirit.

*****

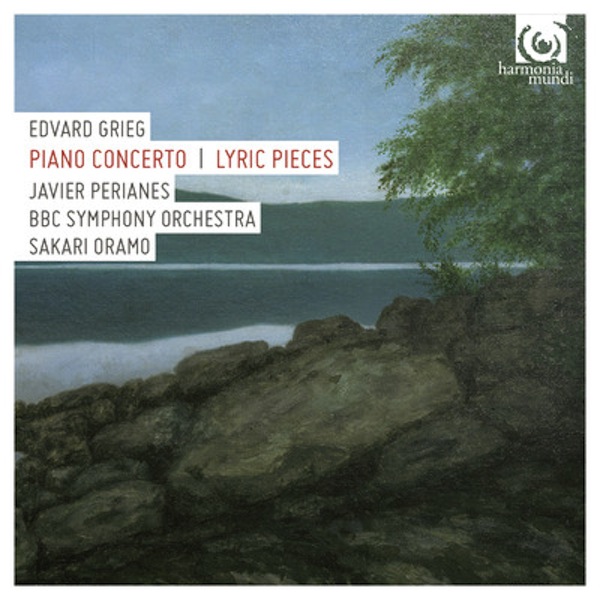

Javier Perianes’ recording, on the other hand, which pairs the Grieg Concerto with a selection of twelve of Grieg’s Lyric Pieces, is thoughtful throughout. The first movement of his take on the Concerto features a better sense of color and tone than Kholodenko’s, it’s rhythmically livelier, and, as a rule, feels freer and showcases a more playful understanding of musical character. His execution of the solo part’s flashy turns are texturally clear and have a tendency to jump out at you. Best of all is his magnificent, rhapsodic account of the big cadenza, which in Perianes’ performance is all but a clinic in making pre-composed music sound improvised.

The Concerto’s second movement is sumptuous and gentle, with a great sense of spaciousness and freedom. Perianes’ articulations in the finale have lots of bite (especially his playing of forzando markings and accents) and he delivers both with great intensity as well as an acute observation of dynamic gradations in that movement’s second theme. Throughout, there’s a fine sense of instrumental color and lots of character in the movement’s many flourishes. I particularly liked the contrast between his cadenza in the finale and the start of the following “Quasi Presto” section: the former is strikingly aggressive, while the latter begins very gracefully. His reading features a strong sense of momentum leading to the final slow section and the piano’s heroic final statement thunders grandly.

The BBC Symphony Orchestra and Sakari Oramo accompany with a keen attention to detail. Textures are always clear, rhythm is crisp, and Grieg’s melodic writing sings. Perhaps the recording’s biggest drawback is the fact that the Concerto was taped in the acoustically unfriendly confines of London’s Barbican Center so the balance between piano and orchestra can feel a bit blurred. But even that’s a relatively small complaint: Perianes shows himself here a musician of sweeping, Romantic sensibilities, eager to take a stand in this piece, and the result is a triumph.

Perianes’ selection of a dozen Lyric Pieces to fill out the disc proves a wise choice. The whole collection of Grieg’s Pieces runs to over eighty in number and presents itself as something of a Norwegian take on Mendelssohn’s Songs without Words but with more programmatic titles. Perianes offers a wide sampling here, from a beautiful Arietta (op. 12, no. 1) to a haunting Ensom vandrer (op. 43, no. 2) to a mischievous Trolltag (op. 54, no. 3) with its hints of the “Hall of the Mountain King” to an expansive For dine fodder (op. 68, no. 3) and a lilting Efterklang (op. 71, no. 7). He’s clearly at home in this music and loves it: the playing’s warm, unhurried, and rich in detail.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: BBC Symphony Orchestra, Grieg, Harmonia Mundi, Javier Perianes, Sakari Oramo