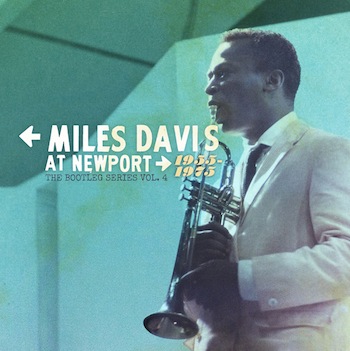

Jazz CD Review: Miles Davis at Newport — Indispensable

Miles Davis at Newport, 1955-1975 has its drawbacks, but I wouldn’t want to be without this four-disc collection.

Miles Davis at Newport, 1955-1975: The Bootleg Series, Volume 4. Columbia/Legacy 88875081952 (4 cds)

by Michael Ullman

This four-disc collection brings together eight sessions with Miles Davis, five of them recorded in Newport, Rhode Island, two in Europe, and a single number, “Mtume,” from Avery Fisher Hall in 1975. These are hardly bootlegs. Eleven cuts have been previously issued by Columbia in one place or another, including the entire session featuring John Coltrane and Bill Evans (from Newport, 1958). Still, the pre-issued numbers have never been gathered in the same place, and we have not heard the other sessions, such as the 1973 Berlin performance, which are described in the liner notes as deriving from a “Tape source from the collection of the Producers.”

Everyone agrees that Newport was important to Davis’s career. In 1955, he had just been through the first rough spell in his career. He had left the public eye to deal with the heroin addiction that earned him the reputation of being unreliable at best. He was back, and healthy, but few people had noted it, despite the fact that in 1954 he had recorded two masterpieces: his LPs Walkin’ and, with Thelonious Monk on the title cut, Bags’ Groove. He had a binding recording contract with Prestige Records, but wasn’t yet a star. Newport 1955, George Wein’s second festival in that city, changed that, but it’s unclear exactly how. The oft-repeated story is that Miles Davis was added to the roster at his own request; his appearance had not even been advertised.

Davis appeared, looking slick and handsome, and played three numbers including a version of “Round Midnight” accompanied by its composer, Thelonious Monk. The crowd’s reaction is the source of contention. It is usually asserted that the crowd went wild, in particular for Miles. In Davis’s autobiography (as told to Quincy Troupe), Miles (or Troupe) describes the response to the trumpeter’s “Round Midnight”: “I played it with a mute and everybody went crazy… I got a long standing ovation. … It was something else, man, looking out at all those people and then seeing them suddenly standing up and applauding for what I had done.” One member of the audience was record executive George Avakian, who afterward signed Davis to a deal with Columbia. That was the real turning point.

Yet Avakian remembered the reaction to Davis’s Newport performance as being lukewarm. Now that we can hear the three numbers (incidentally not in the order that Davis remembers playing them), listeners can judge for themselves. It doesn’t sound like hysteria to me. Musicians might have recognized the special importance of Davis’s playing that night: the rest of the audience sounds appreciative, but not any more so than when Monk or the others solo.

Miles Davis performing in 1972. Photo: Michael Ullman.

After the show, Monk told Davis that he had played “Round Midnight” incorrectly. (Monk was a stickler for the correct chords when others were playing his compositions.) That shouldn’t make a whit of difference when it comes to our appreciation. The “Newport ’55” set is fascinating, not least for the opportunity of hearing Monk perform with Miles Davis. The solos by the two on “Round Midnight” are riveting. I never imagined I would hear lighter-than-air swing, but tenor saxophonist Zoot Sims skates and skims with anti-gravity ease over Monk’s almost aggressive accompaniment. (It reminds me of the way Ben Webster made his separate peace with the irrepressibly virtuosic pianist Art Tatum.) After a ragged theme statement, “Now’s the Time” becomes a series of blues solos, beginning with Gerry Mulligan’s playfully evasive statements. Miles’s solo contains some phrases he might have remembered from his Bags’ Groove on Prestige: Monk’s solo, with its appealingly odd repetitiveness, recalls that studio performance as well.

Davis next appeared on At Newport 1958: all of the numbers from that session with his sextet have been previously issued on LP, either on Miles and Monk at Newport or on the anthology Happy Birthday Newport (both Columbia/Legacy). Those who haven’t heard the session will be delighted to hear Davis dancing over Paul Chamber’s bass on his “Fran-Dance,” along with Cannonball Adderley’s hyper-active choruses and Coltrane’s rugged, squawking solo. There’s another recording of “Bye, Bye Blackbird,” one of Davis’s deservedly favorite ballads of the time.

Davis didn’t return to Newport until 1966. Then, and at the 1967 festival, Davis appeared with his second quintet, featuring Wayne Shorter along with Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams. What a difference a rhythm section makes! Williams opens the 1966 version of “Gingerbread Boy” with an energized, and somehow loose, drum introduction. Davis enters and his trumpet virtually crackles with intensity: he plays in the higher register of the horn and with great force. Perhaps he felt he had to to be heard over the Williams, yet the drummer seems to withdraw when Shorter enters. (It is interesting to compare this “Gingerbread Boy” to the more raucous Newport version of 1967.) In 1966 the band reprised Davis’s “All Blues” from Kind of Blue. In 1967 the band plays a fast, almost impatient, version of “So What.” Of course, “So What” on Kind of Blue is one of Davis’s most celebrated recordings. The band in Newport could have wrestled with what literary critic Harold Bloom called ‘the anxiety of influence.’ Instead, they blow right by the earlier recording. When Davis starts to solo, Williams enters with a sizzling cymbal beat faster than feet can tap. This Newport performance is also notable for Davis’s subtly different version of “Round Midnight,” with the trumpeter supplying unusually clipped phrases: it’s as if he wants to remind us of the tune rather than play it. When Shorter enters, Williams virtually explodes and the band goes into double-time.

Miles Davis in 1972. Photo: Michael Ullman

The last two discs, recorded between 1969 and 1975, all feature the electrified bands that Davis led after his seminal recording, Bitches Brew. He boasted that he would put together the best rock and roll band ever. Maybe he did. But the group didn’t gel on July 5, 1969. Shorter found himself stuck in traffic, so Davis recorded with a quartet that features Chick Corea, Dave Holland, and Jack DeJohnette. DeJohnette keeps a generally solid, though still flexible, beat. On “Miles Runs the Voodoo Down,” Corea, on electric piano, comes off as a wilder version of Hancock: he plays long, scalar runs and then hunkers down for tightly compacted, dissonant chords that bite hard. The group recorded only three numbers that day, but they are unique. The collection then goes out of chronological sequence to offer Davis’s set in Berlin from 1973 and the single number from Avery Fisher Hall before devoting all of disc four to the trumpeter’s 1971 performance with another great saxophonist, Gary Bartz, and with Keith Jarrett on keyboards. That set took place in Switzerland.

The 1973 German session is the least formal. There are long jams here that have been given names such as “Turnaroundphrase” and “Untitled Original.” There are two versions of “Tune in 5.” In them, Miles plays with a wah-wah pedal that distorts and intensifies his originally beautiful sound. The rhythm section is rocking: this is a funk band doing group improvisation and I find it stimulating. By contrast, the 1971 session, also electrified, sounds clean and precise. It is notable for a 25 minute version of “Funky Tonk.” Though 1975 started with the concert that became the double album Agharta, it was also the year in which Davis finally became too ill to play. “Mtume” starts with a conga solo by drummer Mtume Heath; the recording sounds harsh, no doubt because it was taped in the cavernous Avery Fisher Hall. Davis sometimes sounds lost in the mix. With his shortened phrases and long pauses, he seems to be figuring out what to make of a diminished talent.

Davis had a reputation for being cantankerous. Yet when I went to hear him live, he was always on time or early: he seemed at least willing to talk. He was also a professional, and in at least one way courteous: every one of these Newport sets is well-assembled and concise enough to fit the tight format that Wein had established. “A little showbiz don’t hurt sometimes,” he said in his autobiography. He was a great showman as well as a great musician. This collection has its drawbacks, but I wouldn’t want to be without it.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: 1955-1975: The Bootleg Series, Columbia/Legacy, Miles Davis at Newport, Miles-Davis, Newport