Classical Music Feature: Fifty Years Later, Jacqueline du Pré’s Elgar Remains the Gold Standard

There is something undeniably affecting about Elgar’s composition and cellist Jacqueline du Pré realizes it all with an unbridled depth of feeling.

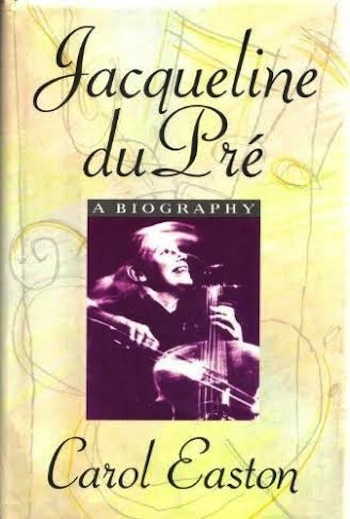

Cellist Jacqueline du Pré — considered by many to have been one of the greatest prodigies and classical soloists of the 20th century. Photo: Allegro Films.

By Jason M. Rubin

On August 19, 1965, Sir John Barbirolli, a cellist-turned-conductor with 40 years of experience leading orchestras, entered London’s Kingsway Hall to record Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E minor with the London Symphony Orchestra and a 20-year-old phenom: Jacqueline du Pré, now considered one of the greatest prodigies and classical soloists of the 20th century. This would be the recording that would cement that reputation and provide the conductor with the realization of his long-held dream of making Elgar’s music more broadly known throughout the world.

Despite her age, du Pré was no ingénue. Born on January 26, 1945, in Oxford, England, she began lessons on the cello at age five. Her progress was both rapid and remarkable. At the age of 11 she won the prestigious Suggia Award, which paid for private lessons with William Pleeth, who taught her the Elgar when she was 13. Four years later, on March 21, 1962, du Pré performed it at her Royal Festival Hall debut. The reviews were so rapturous — how could a young girl so beautifully express the brooding despair of such an elegiac work?– that the piece instantly became a standard part of her repertoire and she and the Elgar have been inextricably linked ever since.

The Elgar was also on the program when du Pré first performed under Barbirolli’s baton on April 7, 1965, at the Royal Festival Hall with the Hallé Orchestra. She performed it again the following month for her U.S. debut at Carnegie Hall, with the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Antal Doráti. Everywhere, she was a sensation and everyone wanted to hear her do the Elgar. Clearly, the time had come to make a recording.

The day I discovered du Pré

Sometime in the winter of 1999, I was working in downtown Boston. Walking from the MBTA subway stop at Government Center to get to my office, I noticed a new store just opened called Buck a Book. True to its name, nearly every book in the shop was just $1. In most cases, they were publishers’ overstocks or discontinued titles.

I can’t recall if it was my first time in the store or a subsequent visit, but on one occasion I noticed a double-width stack of books that extended from the floor to my waist. I was attracted to them by the photograph on the cover: a purple duotone of what appeared to be a manically possessed female musician with a cello, her hair and fingers blurred by her ecstatic playing. Looking closer, I saw it was a biography of someone named Jacqueline du Pré by someone named Carol Easton.

I picked up a copy at the top of the stack, a first-edition, jacketed hardcover. Published by Summit Books in 1989, the title had apparently not interested American readers all that much, perhaps because this was a classical music performer they hadn’t seen on a PBS pledge special. Being a music lover, though with much to learn about classical music, I gave up a buck and it has paid off far more handsomely than any scratch ticket I ever bought.

Before I was halfway through the book, I decided I had to hear du Pré’s music for myself. I went to Tower Records and purchased a three-CD set (also from 1989) called Favourite Cello Concertos, including two by Haydn and works by Boccherini, Schumann, Saint-Saëns, Monn, Dvořák, and, of course, Elgar. Though a far heftier investment for me than the dollar I spent on the book, if half of what Easton described in words would be true to my ears, I knew it would be well worth the cost.

I knew nothing about Elgar or his concerto beyond what I read in the book. Once I heard the CD set, I was dumbstruck. I enjoyed all the concertos; some — the Schumann, Saint-Saëns, and Dvořák — are as good or better than the Elgar, but it was the Elgar that moved me to tears and it still does to this day, with every listen. There is something undeniably affecting about the composition and du Pré realizes it all with an unbridled depth of feeling.

A composer with a cause

Born in England in 1857, Edward Elgar was well known for such works as the Enigma Variations (1899) and the Pomp and Circumstance marches (the first, from 1901, is the one you graduated to). He became quite popular and successful in his native land and visited the U.S. four times. Yet he despaired at the carnage of World War I and towards the end of the war underwent surgery for an infected tonsil that was considered risky at the time for a man in his 60s.

Elgar began his cello concerto while recovering from surgery, then put it aside while he completed three other works. Finally, in 1919, just months after the war ended, the concerto was completed as Opus 85 in his canon. Structured in four movements, the piece has the feel of a great lament for the destruction his homeland had suffered. The concerto had its premiere on October 27, 1919 with the London Symphony Orchestra at Queen’s Hall. One of the cellists in the orchestra at the premiere was a young John Barbirolli.

Due to insufficient rehearsal time, however, the premiere did not go over well. Elgar’s music gradually fell out of favor with the English public and after his wife died in 1920 he turned to other hobbies, such as chemistry and attending horseraces. He was very interested in recording technology, and in fact recorded the cello concerto in 1920, with female cellist Beatrice Harrison as the featured soloist. Ironically, Harrison died just 28 days prior to du Pre’s Festival Hall debut. Elgar died in 1934 of cancer, the cello concerto being his last significant work.

The recording itself

Though du Pré allegedly enjoyed telling people the concerto was recorded in one take, in fact it took 37 takes pieced together to comprise the legendary recording. It matters little, since the overall effect is seamless, thanks in no small part to EMI’s brilliant producer, the late Suvi Raj Grubb.

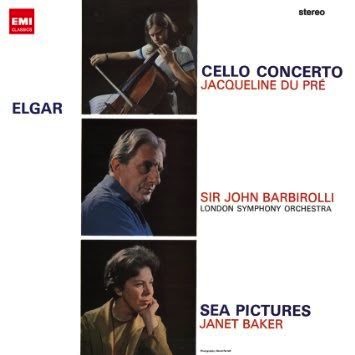

Released in 1965 as EMI 0724356288720, the concerto was paired with Elgar’s Sea Pictures, a song cycle performed by mezzo-soprano Janet Baker. According to Easton’s book:

“[T]he record has never been out of print, and is now considered a classic. But although the Elgar meant a great deal to Jacqueline, it was never her favourite. The music critic Robert Anderson, who was with her when she first heard the recording, has written, “She burst into tears and said, ‘That was not what I meant at all!’”

And yet, on hearing her recording, the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, with whom du Pré once studied, removed the Elgar from his own standard repertoire, admitting, “My pupil, Jacqueline du Pré, played it much better than I.” On the website of the Elgar Museum, the recording is described as, “One of THE most famous recordings in the whole of classical music — and rightly so!” To this day, the du Pré/Barbirolli is widely considered the definitive recorded version of the Elgar cello concerto.

It may be of some interest to note that the cello du Pré used on this and most of her most famous recordings, known as the Davidov Stradivarius, built in 1712, has been in the possession of Yo-Yo Ma since her death.

More about Jacqueline du Pré

When she married pianist/conductor Daniel Barenboim in 1967, classical music had its greatest husband and wife team since Robert and Clara Schumann. What’s more, this was the jet-set ’60s and in the midst of Beatlemania they were accorded superstar status. Sadly, it was not to last. Jacqueline du Pré died on October 19, 1987, after a long struggle with an aggressive form of multiple sclerosis. She was diagnosed in 1973, at least two years after her first symptoms appeared. Her remarkable career thus ended at the age of 28.

Emily Watson as Jacqueline du Pré in the 1998 film “Hilary and Jackie.”

The more I have learned about du Pré from various sources, the more I realize that the biographies about her are not very objective. Easton was a friend of du Pré’s late in her life, when she was already very ill. Barenboim and du Pré’s sister and brother, Hilary and Piers, refused to be interviewed for the book. The latter two no doubt refused to cooperate because they were planning on releasing their own book, A Genius in the Family, on which the 1998 movie Hilary and Jackie, was based (the book was published in the U.S. with the same title as the film).

When their book was finally published in 1997, it caused an uproar in the classical music community because of its sensationalized account of an affair Jacqueline had with Hilary’s husband, apparently with Hilary’s consent. (The older Hilary was a talented flutist, by some accounts more accomplished for a time than her sister, but “Jackie” soon overtook her and from then on the family’s focus was directed at launching and sustaining the younger girl’s career. For that reason, many have accused Hilary of deliberately trying to knock her more famous sister off her pedestal.) The movie, despite exceptional performances by Emily Watson as Jackie and Rachel Griffiths as Hilary, pushes this bombshell revelation and the effects of du Pré’s illness to a prurient extreme. It should be noted that, having seen the script, neither Barenboim nor EMI chose to cooperate with the filmmakers.

A third book, Jacqueline du Pré: Her Life, Her Music, Her Legend (1999), by Elizabeth Wilson, is also compromised. It was authorized by Barenboim, which means he had say over what went in and what was left out (though du Pré’s affair with her brother-in-law, and Barenboim’s own less-secret affair with a woman he had two children with while Jacqueline was still alive, are mentioned, albeit briefly). Wilson, a cellist herself, was a friend of du Pré’s as well and was quoted several times in Easton’s book.

Clearly, then, the only source we can trust is her recordings, both audio and video, and those are highly recommended. It is fitting that it is through du Pré’s music that we learn the most about her; the enormous tragedy of her pitifully short life and career are nowhere more explicitly and movingly expressed than in her prescient performance of the Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, her first recording of it now marking its golden anniversary.

Jason M. Rubin has been a professional writer for 30 years, the last 15 of which has been as senior writer at Libretto, a Boston-based strategic communications agency. An award-winning copywriter, he holds a BA in Journalism from the University of Massachusetts Amherst, maintains a blog called Dove Nested Towers, and for four years served as communications director and board member of AIGA Boston, the local chapter of the national association for graphic arts. His first novel, The Grave & The Gay, based on a 17th-century English folk ballad, was published in September 2012. He regularly contributes feature articles and CD reviews to Progression magazine and for several years wrote for The Jewish Advocate.

Tagged: Edward Elgar, Elgar Cello Concerto in E minor, Jacqueline du Pré, London-Symphony-Orchestra

So glad to read this. In addition to being a fabulous performer, she inspired so many girls to take up the cello. I adored her and was so saddened by her illness. Nice tribute!