Visual Arts Review: “Van Gogh and Nature” at The Clark — Beyond the Myth

In Van Gogh and Nature, human beings play a supporting role. Sometimes moths, butterflies, and poppies are the stars.

Van Gogh and Nature, The Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, through September 13.

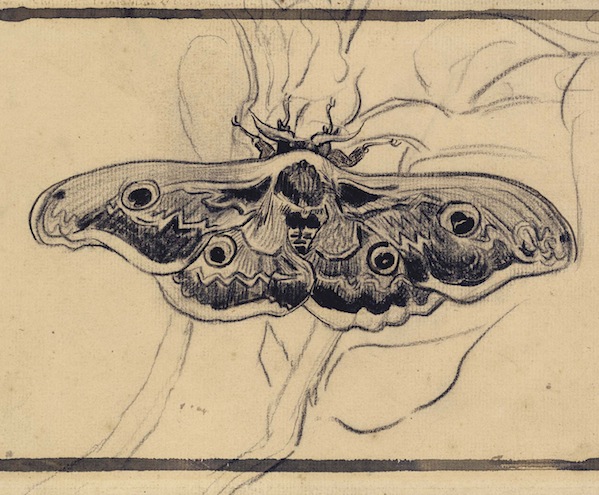

Vincent van Gogh, “Giant Peacock Moth” (partial view), Saint-Rémy 1889. Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institution.

By Peter Walsh

The Clark’s Van Gogh and Nature sets out to do the impossible: take one of the best known artists in history, whose cinematic popular mythology is carved deep into basalt, and completely remake his brand. It succeeds. The van Gogh you remember when you enter the first gallery is not the same one you know when you leave the last gallery.

This is such a clever trick that it seems, at first, like slight of hand. It is not. Though the show’s organizers have made their choices with calculation, you leave convinced that their version of van Gogh is far truer than the hoary clichés.

The premise begins with omission. Van Gogh had some rather old fashioned ideas about the hierarchy of genres. Like the French Academics, he thought that any work of art that focused on the human figure was more important than any work that did not. In fact, by the time van Gogh decided to become an artist, landscape had become the de facto leading genre of 19th-century painting. No longer a minor, decorative genre, landscape was at the cutting edge, where aesthetic boundaries were being pushed forward. In the early years of the twentieth-century, in the hands of artists like Kandinsky and Mondrian, landscape became the pathway to complete abstraction.

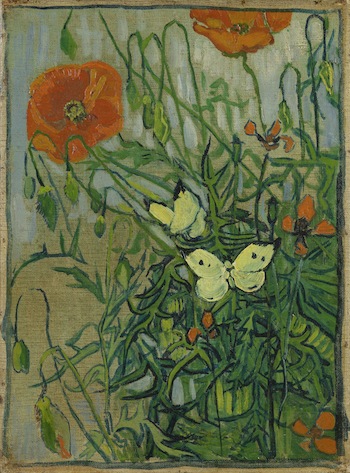

True to his academic ideals, van Gogh, in fact, did focus on the human figure for much of his career. The Clark exhibition all but eliminates that as a theme. Van Gogh’s early masterpiece, “The Potato Eaters” is not included nor are the claustrophobic interior scenes he painted later in Arles. Of all van Gogh’s many portraits and self-portraits, mostly of key people in his life, including himself, only one small etching of van Gogh’s late life friend, Dr. Gachet, makes the curatorial cut. In this show, human beings play a supporting role. Sometimes moths, butterflies, and poppies are the stars.

![Vincent van Gogh, "Cypresses," [] Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.](https://artsfuse.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Cypresses.jpg)

Vincent van Gogh, “Cypresses,” 1889. Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

Most especially, the elimination of the haunted self portraits, including the icon images of the artist with a bandaged ear, shifts attention away from van Gogh the half-savage tortured soul and towards van Gogh the intelligent, enthusiastic, sophisticated, deliberate, and extraordinarily talented creator of intensely original works of art.

The show, which spans van Gogh’s entire professional career as an artist, also underscores that career’s breathtaking brevity and productivity. The earliest work in the show dates from June 1881; the last ones were made in Auvers in the late spring and summer of 1890, just weeks or days before his death: so less than a decade, but one so packed with work and ideas that it left behind one of the richest artistic legacies in modern art.

What is perhaps most remarkable of all about this exhibition is that you can go from beginning to end without picking up a clue about van Gogh’s turbulent personal life. Instead, you see an artist approaching his chosen career with a deliberate plan, concisely and brilliantly carried out, proceeding by distinct stages until he reaches, and makes full use of, the peak of his powers, which he does until the very end of his life.

When the show opens, van Gogh is in his late twenties, already having failed to take hold of several careers, including work as an art dealer, boarding school teacher in England, and as a lay preacher and missionary to Belgian miners. Yet, as the comprehensive exhibition catalogue points out, those early years were hardly wasted.

In his early twenties, van Gogh had moved from the rural small towns of his childhood in the Netherlands to London, Paris, and the Hague, the center of the Netherlands’ flourishing art market. Working for Goupil & Cie, a large, prestigious, international art dealer and publisher, based in Paris with branches around Europe and in New York City, van Gogh was exposed to thousands of important works by leading European painters. As the son of a minister from a liberal branch of the Dutch Reformed Church, part of a Protestant movement of which English Puritanism is another branch, van Gogh was raised in a religion that emphasized education, rationalism, and unadorned piety. As van Gogh prepared for a serious professional career as an artist, all of these influences came into play.

At least in the selection presented by the show’s curators, which avoids juvenilia, there are virtually no missteps, no awkward moments, in van Gogh’s creative journey. Instead, in early works like “The Parsonage Garden in the Snow” (1884-5), van Gogh has already absorbed the ample lessons of the French Barbizon School half a century earlier and the Dutch landscapes of Anton Mauve and other painters of the Hague School, contemporary with van Gogh’s youth. A few well chosen examples by some of van Gogh’s favorites, including Mauve, Daubigny, Dupré, and Théodore Rousseau, show how well van Gogh already measured up to his masters even at this early stage.

Vincent van Gogh, “Butterflies and Poppies,” 1889. Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

In these early works, van Gogh paints in what the show’s curators call “the sombre tones” of Millet and Rousseau. In cases in these galleries there’s an illustration from Charles Blanc’s work on color theory, a major source of van Gogh’s color technique later in his career, illustrations from natural history books, and examples of the contemporary literature he was exposed to, including Charles Dickens. This material shows a painter widely read and acutely observant of and conversive with his own culture. His many letters, written in Dutch, English, and French, are full of enthusiasm for discoveries in art, culture, and natural life.

The catalogue also makes van Gogh’s debt to classic 17th-century Dutch landscapists, especially Jacob van Ruisdael, clear. Here are the straight-edge horizons, the vast northern skies, the intimate relationships between nature and the human-formed landscape, created by centuries of habitation. Here are also the unpolished rural views, shaded forest corners and rows of trees, nature not tidied up, that the Barbizon and Hague Schools favored.

From the Netherlands, the exhibition moves quickly, month by month, through the chapters of van Gogh’s artistic life: Paris, Arles, and Saint-Rémy in Provence, and finally the last months in the town of Auvers, not far outside Paris. Van Gogh’s painting responds to each new environment with transformations and new strengths.

In Paris, in 1886, van Gogh quickly adapted the bright, “divided” colors he saw in the French Impressionists and Post-Impressionists. He also drew on their explorations of the haphazard urbanization of the French capital. Vincent lived with his art-dealer brother, Theo, in the still partly rural district of Montmartre, with its sweeping views of the city below. “The Hill of Montmartre with Stone Quarry” and the drawing “View of Montmartre” (both 1886) and “Montmartre: Windmills and Allotments” (1887) show the fringes of Paris caught between the middle ages and the industrial present, with windmills and small garden plots coexisting with the production of building materials and rapid urban development. In “Terrace in the Luxembourg Gardens” (1886) and “Square Saint-Pierre” (1887) van Gogh explores the Parisian parks, finding in their placid, urban order a counterpart to the Dutch rural landscapes he painted at home. His Paris paintings included a large number of lavish flower paintings, which he tried to sell.

When the story turns to Arles in February 1888, the most dramatic chapter of Vincent’s personal life unfolds. Here, in Provence, van Gogh found new inspiration in the parched, Mediterranean fields and weathered stands of Cypress trees, ringed by rugged mountains and drenched with merciless sunlight. Here van Gogh painted light-drenched olive groves and fields, the “hard blue” sky above Arles and the “great bright sun.” His letters are full of his enthusiasm for his new surroundings and the work he was creating there. In June 1886, he recreated Millet’s heroic peasant, “The Sower,” laboring in the southern heat.

The personal upheaval that followed the visit of Vincent’s close artist friend, Paul Gauguin, seem all but invisible in the works chosen for the exhibition. Although the precise circumstances and events are unclear, it was then that van Gogh, following an argument with Gauguin, famously cut off all or part of his ear. The episode ended with van Gogh’s physical and mental collapse. A stay in the local hospital, and his commitment to a mental asylum in nearby Saint-Rémy, wrapped up his time in Provence.

Vincent van Gogh, “Rain-Auvers,” 1890. Photo: Courtesy of the Clark Art Institute.

At the hospital, where he stayed a bit over a year, van Gogh was encouraged to paint in the former monastery and in its extensive grounds, with beautiful gardens. Some of the most famous paintings in the exhibition date from these months. They include “Cypresses” (1889), “The Olive Trees, Saint-Rémy” (June-July 1889), and “Mountains at Saint-Rémy” (July 1889), works in which van Gogh seems to be completely himself in his painting. Built up of brilliantly-colored, carefully placed brushstrokes, these images are full of wind and light. Everything is in rapid motion, as if the artist has finally tapped the root source of creation itself.

The last section of the exhibition is devoted to the few months van Gogh spent in the town of Auvers-sur-Oise from May 1990, which ended with his suicide in late July. The paintings show an artist very much at the height of his powers. The works on view include “Houses at Auvers,” familiar from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, where it has been part of the collection since 1948, and the strikingly original “Rain-Auvers” (1890), inspired by a well-known Japanese woodblock print by Hiroshige. Van Gogh adapts the horizontal bands of color and the diagonal lines, representing falling rain, of Hiroshige’s composition, but reverses the vertical format to a broad horizontal, stretching the image to a panorama that seems to anticipate the purified forms of the Abstract Expressionists. Here, even near his end, van Gogh still has not given up on his pursuit of the ultimate. In a famous quotation in an unfinished letter, he writes “before such nature I feel powerless.” But he certainly was in command of his own artistic power in depicting it.

The well-presented, beautifully produced, and extremely thorough catalogue for the show, distributed by Yale University Press, makes a permanent record of the insights and revelations of the exhibition and expands on them (though a general reader might appreciate slightly less academic prose). Alas, the inevitable museum sale shop that follows the exhibition is chockfull of the usual ‘suffering artist’ clichés: coffee mugs, puzzles, and t-shirts with bandaged ears galore. It will take more than one exhibition to banish the myth.

Peter Walsh has worked for the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, and the Boston Athenaeum, among other institutions. His reviews and articles on the visual arts have appeared in numerous publications and he has lectured widely in the United States and Europe. He has an international reputation as a scholar of museum studies and the history and theory of media.

I enjoyed this excellent discussion of a beautiful show, but I was sad and frustrated to see the same old tired myth of VG’s suicide casually mentioned. I refer anyone interested in the truth to Van Gogh: A Life by Naifeh and Smith, Pulitzer Prize winning scholars who discuss at length the interviews given in Paris by an old man who was a teenager in Auvers with VG. He was also responsible for VG’s death, in that he had “borrowed” a revolver from the landlord’s daughter, and when Vincent tried to take the gun from the two boys’ pack, the gun went off. There is other ample documentation; it really is time to put an end to the slander. I hope more scholars, curators, critics, and plain old art lovers will do their part to respect this great artist and mourn his accidental death at the height of his powers.