Poetry Review: James Tate’s Last Poems — Dense, Daffy, and Original

In his final collection of poetry, James Tate remains true to himself. These prose-poems are often stellar, harrowingly distinctive, and worthy of repeat visits.

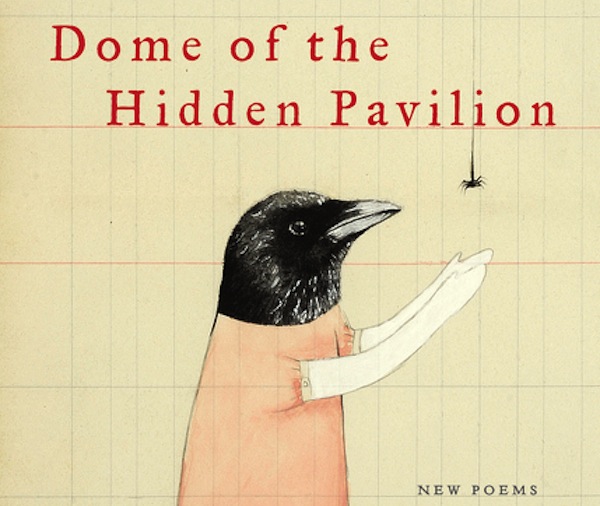

Dome of the Hidden Pavilion by James Tate. Ecco Press/HarperCollins, 160 pages, $25.99.

By Robert Israel

James Tate, a longtime professor at University of Massachusetts in Amherst, died July 8 at age 71. His passing took place just weeks before the release of Dome of the Hidden Pavilion, his 17th collection of poetry. The book brings together over one hundred selections written in the prose-poem format. It underscores Tate’s lifelong quest to invent new ways to express his poetic voice.

Poets have long flirted with writing what Charles Baudelaire once called “small poems in prose.” Baudelaire showcased his in Paris Spleen (1869). American poet W.S. Merwin followed a century later in The Miner’s Pale Children (1970). The comparisons with Tate end there. Merwin dealt with variations on the theme of isolation, Baudelaire with opiated decadence. Tate blazes a different path. He is a trickster intent on taking us on beguiling journeys where what appears to be sensible is anything but, and what seems inane gibberish achieves remarkable lucidity.

I first met Tate during his (and my own) formative years, and have avidly followed his work over the years. His last collection is evidence of his dedication to an earlier declaration of his poetics: Tate demanded that he be as free to explore his muse in as many different ways as possible. What follows are a few words on my early encounter with Tate:

“We were all set to dismiss him when he showed up at our college’s lecture hall. A native of Kansas City, Mo., he acted the hayseed. He opened his reading by cracking a few jokes — something along the lines of the farmer’s daughter who meets the traveling salesman. He was met with audible groans.

So Tate dropped his ‘Aww shucks’ shtick and the ‘I’m from the Show Me State’ hokum and set forth on a snarky ramble about being a browbeaten by his professor to read aloud for course credit. We could relate: our attendance at his reading was mandatory. Besides, many of my fellow classmates and I likened reading poetry — never mind writing or reciting it — to a trip to the dentist for a tooth extraction, without Novocain.”

Tate was a skilled room jockey. He kept his audience surprised and engaged. During that reading, he recited poems that probed the depths of the human predicament. These included a poignant tribute to his father who died in a bombing mission during World War II, a father he never met. It made us ache. Another poem casually described walking his dog and encountering a portentous figure on the outskirts of his town: it was really about rural angst.

Tate wasn’t finished with us. The next day he showed up unannounced in our classroom. Our teacher had provided him with copies of our works-in-progress. He had red penciled each page. In plain talk — no wisecracks this time — he told us just what we didn’t want to hear: we needed to be less self-conscious and more disciplined if we ever expected to become better writers.

Tate made a career of popping into the culture, and he remains the uninvited guest, having his rousing say, in his final book. He delights in teasing, unnerving, and surprising the reader. But this collection will not be for everyone; it cannot be read through at one or even three sittings. Despite their snippet length and blunt staccato sentences, the pieces are dense and more than a little daffy. Many seem to be parables. Other of the prose-poems emerge as if the poet had recorded his dreams in shorthand. Throughout, one encounters absurd conversations between strangers on the street, friends riding in a car, husband and wife.

One day I said to a captain, “Do you have any idea where we are?” He said, “Of course not. I haven’t any idea.” “Then perhaps we ought to turn back,” I said. “Back where? Ever since I broke my toy compass we’ve been lost. It’s all the same to me,” he said. “Well, we’ve got to do something,” I said. “I’ll do anything,” he said. “Follow a gull,” I said. “Why would I follow a gull?” he said. “Because they fly back to land,” I said. “Yes, that’s a good idea,” he said. But we didn’t see any gulls. (“Lost at Sea”)

Dome of the Hidden Pavilion is chockablock with this kind of antic banter. (Tate’s version of Kubla Khan’s “stately pleasure-dome”?) The reward, ultimately, is that you will be transported to a turbulent land — created by a playful consciousness — that seems both familiar and newly minted. Playwright Sam Shepherd described this surreal territory in his book of prose pieces Day Out of Days: “I now have an almost constant swirling chatter going on inside my head from dawn to dusk…I guess it’s been slowly accumulating over all these sixty-some years; growing more intense, less easy to ignore.”

Poet James Tate — he delighted in teasing, unnerving, and surprising the reader.

As he faced his last days, Tate, like Shepherd, had a “constant swirling chatter” in his head that gave him no rest. So he wrote down what he heard.

Tate once summed up his work in an interview with the Paris Review:

“I love my funny poems, but I’d rather break your heart,” Tate said. “And if I can do both in the same poem, that’s the best. If you laughed earlier in the poem, and I bring you close to tears in the end, that’s the best. That’s most rewarding for you and for me too. I want ultimately to be serious, but I can’t help the comic part. It just comes automatically. And if I can do both, that’s what I’m after.”

In his final collection, Tate remains true to himself. Dome of the Hidden Pavilion is often stellar, harrowingly original, and worthy of repeat visits.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com

Tagged: American poet, Dome of the Hidden Pavilion, James Tate, Poetry

Love this review, Bob. Haven’t kept up with Tate, but I’d like to check this out. Thanks.

[…] 2015 at his home near Amherst. His book, Dome of the Hidden Pavilion (Ecco/Harper Collins), which I reviewed for Arts Fuse, was accompanied by a statement from his editor, Daniel Halpern: “I’m grateful […]