Dance Review: Tom Gold Dance — An Uneven Outing

“Ballet is only good when it is great,” the legendarily unblinking dance critic Arlene Croce once wrote; whenever I bring that judgement to mind it makes me both swallow hard and sigh softly.

Tom Gold Dance, at the Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center, Great Barrington, MA, on June 27.

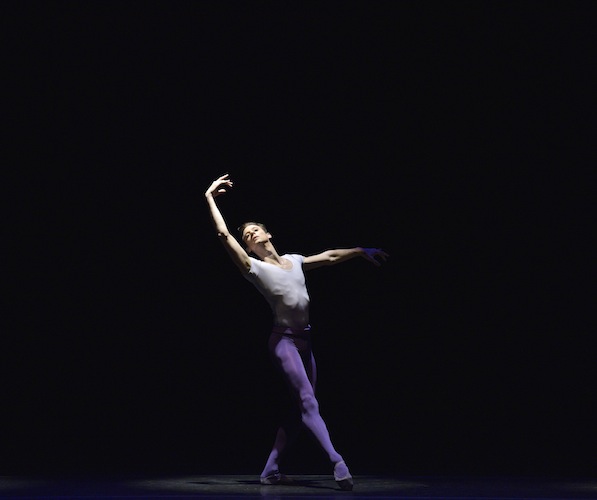

Andrew Scordato performing in “All the Lonely People.” Photo: Eugene Gologursky.

by Janine Parker

In 2008, Tom Gold, then a soloist with the New York City Ballet, joined the ranks of those who break out to form their own little enterprises. Sometimes these undertakings are discrete, one-off performances; they can also be expanded out into a kind of ad hoc mini-tour, often staffed by a headlining name with colleagues, usually otherwise gainfully employed, hired for the gig. Although Tom Gold Dance as an organization is an ongoing entity, its performances, such as the recent one at Great Barrington’s Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center, are a collection of dancers borrowed from other companies. (A typical practice.)

And, oh, such gems tucked into the strong group assembled almost entirely from City Ballet members, for this, the company’s “Berkshires debut,” particularly Miami City Ballet principal Jeanette Delgado and NYCB soloist Megan LeCrone. It’s tempting to invoke a cliché that these two are worth the price of a ticket alone—and indeed, stars like these are for many audiences the main attraction—but overall the program was uneven and underwhelming.

The two strongest pieces of the five were Gold’s 2015 All the Lonely People, performed not to The Beatles, but to a J.S. Bach suite played live by Boston Symphony Orchestra violist Michael Zaretsky (a bright aspect to the show was live accompaniment for three of the dances) and Jerome Robbins’ 1982 Concertino. Although this dance for three, set to an Igor Stravinsky score, is not considered to be one of Robbins’ strongest, on this program it nonetheless bore an air of compositional confidence—the mark of a master choreographer—that was enhanced by the drolly spirited performances of Daniel Applebaum, LeCrone, and Andrew Scordato. There are many references to Robbins’ longtime colleague at City Ballet, George Balanchine, in particular to the masterpiece Agon, one of Mr. B’s own Stravinsky ballets. Whether Robbins was playfully quoting or poking fun is a matter of opinion, but here it felt like a frisky lark. LeCrone was particularly feline, while all three caught Robbins’ nuanced musicality, creating a fleet crispness to the group sections.

With a beautifully melancholy pas de deux at its core, All the Lonely People is also musically sophisticated; in the quicker sections, timing fell apart here and there, nothing egregious—and likely the result of not quite enough rehearsal time with Zaretsky—but in those moments Gold’s choreography looked busy rather than, as it deserves, tightly designed. Though Delgado and Scordato ultimately aren’t an innately complementary pairing—she is richly grounded with a mature fullness to her movements while he is airier, with a graceful but somewhat fragile use of his limbs; a Young Werther to her Anna Karenina—this adds to a sense that their gentle duet is a memory of an affair past, adding to the dance’s poetry. After, Delgado performs her abundance of allégro passages with gorgeous clarity and lovely warmth, seemingly moving into the future while Scordato and corps/witnesses Sara Adams and Kristen Segin end the piece facing back, seeing only the darkness of the upstage abyss.

Gershwin Preludes, from 2009, a duet performed by Likolani Brown and Applebaum, and the 2013 Connect the Dots, a solo for Gold, his only appearance on this program, are fluffy amuse-bouches; both are choreographed by Gold, and though entertaining enough one would have sufficed as a palate cleanser. For them, Zaretsky is joined by pianist Vytas Baksys. In his solo, Gold is charming and understated, and seems bent on showing how many tricks he’s still got up his sleeve: tours en l’air, check; pirouettes à la seconde, check (but with a cheekily-flexed foot); oh, and a little soft shoe routine just for the record. The Gershwin, unfortunately, errs on the side of cutesy pin-up poses for Brown, and some baggy sections which suggest a running out of choreographic ideas.

The ensemble in”La Page” — (l to r): Daniel Applebaum, Likolani Brown, Andrew Scordato, Marika Anderson. Photo: Eugene Gologursky.

The ideas in Gold’s 2013 La Plage, conversely, start promisingly and evocatively, if, given the title, a bit confusedly (projections fill up the backdrop throughout the piece; the first section is an image of a misty forest, not a beach). The dance begins with the arresting image of three dancers, standing but spooned in to one another; they each lift a leg to the side—the different heights recalling Balanchine’s famous Apollo arabesques—before unfurling luxuriously away. They are joined by others who traverse the space both quirkily—sometimes they jump straight up in a soubresaut, their arms pumping sharply up and down, as if birds trying to take flight—and sensuously, chaînés with deliciously rising arms, or hops backward with delicately flicking legs. In this segment John Zorn’s score is peppered with wild sounds — we may be in a tropical jungle. The projection for the second section now gives us a hazy ocean view, superimposed with floating, oversized flowers; dancers’ arms reach out from the wings, then women bourée out from and back into them, as if pulled and pushed by an invisible current. The flashes of imagination peter out however, and by the third section the piece has lost steam and direction; the projections are now trippy, ink-blotty images, and the Zorn score has morphed into Hawaiian surf music. A smoke-‘em-if-you-got-‘em atmosphere, the piece just kind of drifts toward an ending.

“Ballet is only good when it is great,” the legendarily unblinking dance critic Arlene Croce once wrote; whenever I bring that judgement to mind it makes me both swallow hard and sigh softly. It’s true: physically, the genre is so precise of form and so rigorous of execution that there’s little room to hide weaknesses of technique; artistically, there is “only” the body to convey beauty and emotion and story (if there is one), so anything less than full commitment on the performer’s part can be seen for miles. (This was not at issue in this performance; the dancers were very engaged.)

But it is the many elements that have to go into the whole of a performance that I think Croce is talking about, too. Gold’s artistic values seem fine—his dancers are of a high caliber, they are handsomely costumed, and live music in dance has become a luxury that many smaller companies feel they cannot indulge in, so its presence always classes up the joint. Yet this performance had the feeling of a really good, but amateur, recital, brightened by guest professionals. Not quite up to the Gold standard that is most likely within this artist’s reach.

Since 1989, Janine Parker has been writing about dance for The Boston Phoenix and The Boston Globe. A former dancer, locally she performed with Ballet Theatre of Boston, North Atlantic Ballet, Nicola Hawkins Dance Company and Prometheus Dance. Ms. Parker has been teaching for more than 25 years, and has a long history with Boston Ballet School. She is on the Dance Department faculty of Williams College in Western Massachusetts, where she has lived since 2003.