Book Review: “Madison’s Music” — Listen to the Melody of the First Amendment?

If James Madison was so verbose that his draft version of the First Amendment could be cut in half, then he can hardly be called an artist with words.

Madison’s Music: On Reading the First Amendment by Burt Neuborne. The New Press, 272 pages, $25.95.

By Blake Maddux

In the first line of Madison’s Music, author (and attorney, NYU law professor, and the guy who played a lawyer in The People vs. Larry Flynt) Burt Neuborne writes, “This is not a work of history.”

This was fine by me because, although I am a history buff, I was prepared – based on the title – for a close, potentially excruciatingly in-depth study of the First Amendment as James Madison, the oft-called Father of the Constitution, conceived of it.

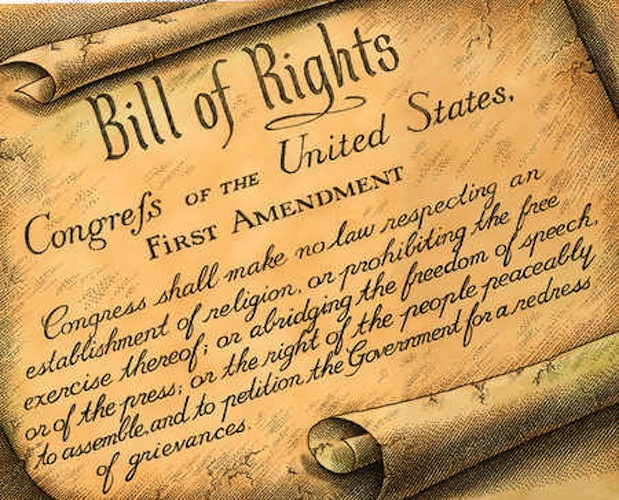

At some point in the book, however, this sentence started to make me consider the possibility that Neuborne doth protest too much. While it may not be the work of a professional historian, Madison’s Music does contain an ample amount of constitutional, legal, and Supreme Court history from which the reader can benefit greatly. For example, many Americans are probably not aware that “The First Amendment as we know it today didn’t exist before Justice William Brennan Jr. and the rest of the Warren Court invented it in the 1960s” or that “The nineteenth and twentieth centuries were free-speech disasters.”

The catch is that there is too much info about events of the distant and recent past for a relatively slim volume that is supposed to be about first forty-five words of the Bill of Rights. In fact, on page 151, Neuborne advises his “dear readers,” as he calls them on more than on occasion, “Those of you…who do not enjoy the louche pleasures of American legal history…may skip to page 171.”

Given that the book contains only 223 pages of text, this is a somewhat significant portion. It is also not the only point at which Neuborne could have suggested that his “dear readers” jump ahead X-number of pages if he or she did not pick up the book in order to learn about something other than what is mentioned on the cover.

So what does Neuborne mean by “Madison’s music”? That turns out to be a bit tricky to understand given that the author just as frequently (if not more so) refers to Madison’s work as poetry and to the man himself as a poet. Not that music and poetry are mutually exclusive, but they are not the same thing, either. Moreover, Neuborne also refers to Madison’s “structural” genius and frequently uses the words “dose” and “antidote.” Thus, with a bit of rewriting, the book could have been called Madison’s Poetry, Architecture, or Science.

However, the word “music” has the advantage (for the sake of the title) of alliteration; it also packs a certain amount of mind, heart, and gut appeal. Since I do not find Neuborne’s case for Madison the musician/poet all that convincing, I will sum up what the author has in mind via this quotation from the last chapter: “There is the music of poetry in the order, cadence, structure, and content of the Bill of Rights, especially the First Amendment, if we are wise enough to hear it.”

Neuborne asserts throughout that if citizens, scholars, and judges (especially Supreme Court justices) read the First Amendment in the same way they take in the entirety of a song or poem, then they would understand the words as Madison meant them to. Not surprisingly, this also turns out to be the way the author understands the intent of the First Amendment, an approach that he believes would have had the most desirable (though not perfect) results.

For example(s), the “democracy-friendly” Madisonian First Amendment would guarantee a constitutional right to vote. This is because, according to Neuborne, voting is “the ultimate act of political expression and association,” both of which are – explicitly or implicitly – guaranteed by the architecture, I mean music/poetry, of the First Amendment.

Furthermore, gerrymandering would be unconstitutional if judges properly heard Madison’s music because it negates potential for a genuinely contestable election, which is, in Neuborne’s words, “the point at which [the clauses of the First Amendment] all converge.”

While I do not disagree that the Constitution does or should guarantee the right to vote and forbid gerrymandering, I am not clear on why Neuborne thinks that Madison did a admirable thing by hiding them in the cloak of music/poetry for future generations to hopefully uncover. Why did he not just state them along with freedom of speech, the press, assembly, etc?

Neuborne says of the Bill of Rights that “Not an idea or a word is out of place.” I would say that not being mentioned when necessary or useful qualifies as out of place.

Furthermore, as the late Mario Cuomo has been all-too-often quoted as saying, “Politicians campaign in poetry but have to govern in prose.” The Declaration of Independence, the campaign brochure for America’s separation from Great Britain, benefitted from being poetic and literary. The document that would actually govern the new nation had to be the contrapuntal prose.

But let us say, for the sake of argument, that James Madison was “a great…political poet like Abraham Lincoln or Ronald Reagan.” Let us say that the Bill of Rights, especially the First Amendment, is a lovely and coherent poem or song. Does Madison really deserve the credit for it being so?

I am not so sure that he does, and Neuborne seems to realize this but hopes that his readers, dear as they may be, do not notice. Although the author does not say exactly what he believes defines music or poetry, I think that we can all agree that a certain economy of words is essential for both. Describing the draft of what would later make up the First Amendment, Neuborne writes, “The [Committee of Eleven] shortened Madison’s wordy version into a single clause about half as long … Score one for the editors. But note that Madison had already settled on the order of the six rights in what came to be the First Amendment.”

It is all well and good that Madison knew which rights he wanted to include in the order in which they would appear. But if Madison was so verbose that his version could be cut in half, then he can hardly be called an artist with words. (In another instance, “The editors shrank Madison’s text from fifty-seven to twenty-one words….”)

Neuborne generously refers to Connecticut’s Roger Sherman as “Madison’s editor-in-chief.” It was Sherman, in fact, who repeatedly proposed that the Bill of Rights stand alone at the end of the Constitution rather than be weaved into its text, as Madison demanded it be. “Sherman,” Neuborne acknowledges, “did Madison—and us—a huge service by insisting that Madison’s music be displayed in a manner that reveals it majestic harmonies.”

Still, in the end, Neuborne gives Madison the lion’s – nay, the entire pride’s – share of the credit for having “already developed the content, order, and structure” and for doing “most of the heavy organizational lifting.” From a musical/poetic standpoint, why does any of this work matter all that much? Neuborne admits that the editors “shrank the text … improved the diction … [and] cleaned up” a great deal of Madison’s draft.

Finally, Madison was certainly not the “reluctant poet” that Madison’s Music describes him as. “Reluctant” affords Madison a certain heroic quality, but “unwilling” would be more accurate. Neuborne repeatedly refers to the pejoratively described “parchment barriers” without ever attributing this phrase to Madison, who believed that a Bill of Rights would not be worth the paper that it was written on.

In truth, Madison’s Music is borderline hagiography. Madison himself wrote in an 1834 letter (not quoted by Neuborne), “You give me a credit to which I have no claim, in calling me ‘The writer of the Constitution of the U.S.’ This was not like the fabled Goddess of Wisdom, the offspring of a single brain. It ought to be regarded as the work of many heads and many hands.”

Author Burt Neuborne — call him “a level-headed advocate of reasonably regulated free speech.”

Perhaps Madison was being a bit modest, but he was also being honest. In questioning whose original intent constitutional “originalists” such as Justice Antonin Scalia look to, Neuborne names several candidates: “Madison’s? The delegates to the Philadelphia Constitutional Convention? The members the voters who elected the members of the various state ratifying conventions? The 1789 Congress that adopted the Bill of Rights? The voters who elected the members of that Congress?”

All of these parties had some sort of impact on the Constitution as it came to be.

There are many other points on which I could criticize this book. E.g., the author who states, “I’m not an expert on Madison’s psyche” goes on to opine that, in response to recent misunderstandings of the First Amendment, “Madison would weep,” “would be appalled,” and “would be aghast.”

But this is not a graduate seminar paper. If it were, I would also explore in greater depth Neuborne’s compelling theory about how the Madisonian First Amendment would afford hearers a more muscular freedom from speech in a fashion similar to freedom from religion. Unlike authors who are invariably described as something like “a zealous defender of absolute free speech,” Neuborne might correctly be called “a level-headed advocate of reasonably regulated free speech.” He is a gifted writer and a calm, non-confrontational defender of his case.

If absolutely nothing else, I learned two things from Madison’s Music that I am certain that I would not otherwise have ever known: 1) What a Shabbos goy is and 2) that there is such a thing as a Shabbos goy.

Despite all of my reservations, I do not mean for this review to discourage any would-be readers. Rather, I want to alert them all of what to expect when they do begin to read it; namely, a pleasurable, amply thought-provoking read that falls short of fully developing its main thesis.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to DigBoston and The Somerville Times. He recently received a master’s degree from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Thesis Prize in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

Tagged: American government, Burt Neuborne, First Amendment, James Madison, Madison’s Music, The New Press