Dance Feature: “Available Light” — Revived at MASS MoCA

Lucinda Childs and her company are preparing for a revival tour of Available Light, a collaborative work created in 1983 with composer John Adams and architect Frank Gehry, that begins in Los Angeles later this year.

Available Light, Choreography by Lucinda Childs, Music by John Adams, Set by Frank Gehry. Lighting design by Beverly Emmons and John Torres. Produced by Pomegranate Arts, Inc. Original premiere Los Angeles, 1983; revival in previews at MASS MoCA, North Adams, Massachusetts, March 6, 7, and 8.

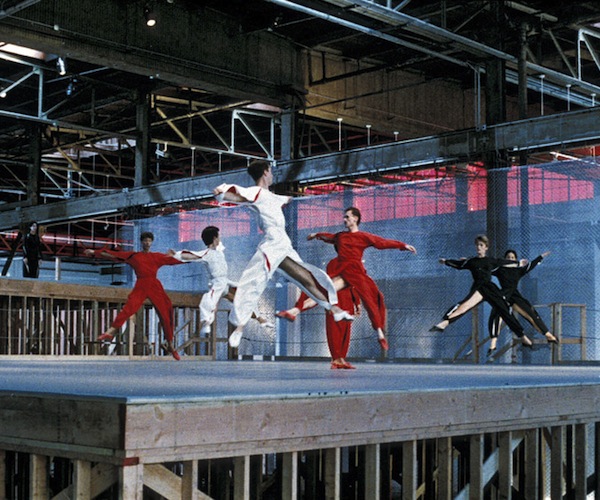

Lucinda Childs reinvents her seminal work “Available Light” with opening showings at MASS MoCA. Photo: Tom Vinetz.

By Janine Parker

Walking, my colleagues and I often tell our students, is one of the hardest things to do in dance. What we mean is: It’s hard to get it right, to take a “pedestrian” movement and make it look like, well, like dance, but not too much like dance…like dancers, walking. (But in a dancerly fashion.) Got it?

In the 1960s, however, a faction of choreographers, in the upsetting-of-the-apple-cart tradition begun by the early moderns who preceded them, began asking a round of impishly provocative questions (“Why”—and maybe more often, “Why not”) which really led to the question of What: What is dance? Steve Paxton, one of the founders of the Judson Dance Theater, not only wondered why dancers couldn’t walk like pedestrians; he wondered why he couldn’t just cast pedestrians in his work and direct them to walk. Like pedestrians. In Paxton’s 1967 Satisfyin’ Lover a handful of non-dancers did just that—they walked across the stage (and stood, and sat) without ceremony.

The Judson experiments were both lauded and booed (and some people just yawned), but for many, they were heady lessons in creative freedom. For some of the collective’s disciples, that freedom also gave them the liberty, if they chose, to chuck the Dadaism. The choreography of Lucinda Childs—whose 1964 Judson-era solo Carnation consists of a droll ritual (which she performed while sitting on a little stool) with sponges, a wire basket, and pink hair rollers—is now known for its technically-demanding ballet-based vocabulary that requires highly-trained dancers. The steps that Childs employs are familiar, and sparingly chosen: chassés, piqués, jetés. Often, even the way she strings them together into phrases is fairly standard, but they are performed with an almost severe exactitude, and with frequent directional changes the dancers must make on the proverbial dime.

“It looks easy,” Childs told me last week, with a tiny, arch smile in her eyes, “but it’s very demanding work.”

Indeed, in Available Light, a collaborative work created in 1983 with composer John Adams and architect Frank Gehry (and which Childs and her company are preparing for a revival tour that begins in Los Angeles later this year), Childs’ dancers execute a series of movement phrases which to a viewer may seem simple, but in fact require intense focus and control on the dancers’ part. The sequences overlap and loop, are developed and deconstructed. Like a house of cards, a step out of sync causes the structure to sway. Legs etch and slice with surgical precision while upper bodies remain eerily erect. “Lucinda’s work is really pared-down ballet,” said Caitlin Scranton, who has danced with Childs since 2009, and “…efficiency is necessary” to move quickly and cleanly.

All of this pure dancing doesn’t mean that Childs left her Judson days entirely behind: The dancers also walk, and stand, quite a bit in fact. Those pauses are more than earned, but unlike most particularly demanding dances where exits are built in, in Available Light the dancers whip and whoosh and then, suddenly, come to a complete halt, where they wait in full view of the audience. The performers seem almost at rest but, on close inspection, look a-shimmer, like engines idling at a stoplight.

Longtime company member Ty Boomershine remembers when he performed the work in the 1994 London revival, that “…to actually stand in 1st position and stay involved, was the hardest…When you’re moving,” he continued with a laugh, “you’re good.” Remaining “involved” is key to the mesmerizing effect generated by pieces such as Available Light, and Childs’ Dance. In a way it’s as much a part of the cast’s training as their daily ballet class. It comes with practice, like the physical stamina that builds throughout the rehearsal process. “I just try to get them to that point where they can open up their own personality…and project in a theatrical way,” Childs said. “Something has to come through that is really coming from them, that’s not phony, that’s not imposed.” The current cast of Available Light all performed in the recent revival of the 1976 Philip Glass/Robert Wilson opera Einstein on the Beach, an experience that Childs believes will help strengthen the presence of this elusive quality.

Choreographed by Childs, Einstein—like Available Light and the 1979 Dance (with music by Glass and film “decor” by Sol LeWitt)—highlights Childs’ passion for collaboration. Whereas the choreographer Merce Cunningham famously made collaborative pieces in which the various components were made separately, deliberately, Childs (who was a student of Cunningham’s) worked closely with her colleagues. While Childs told me that what Cunningham, et al did “…was marvelous,” it wasn’t a process she was drawn to. She wanted to be familiar with the structure that her collaborators were working with, “…not to necessarily illustrate it in any kind of ABC way, but to interact with it, and the only way to do that is to bring everyone together at the outset of the project, to discuss the ideas, of where we wanted to go.”

In Dance, LeWitt’s film of the dancers performing the choreography is projected while dancers perform the same choreography live, on stage, producing a haunting doppelganger effect. That twinning was carried over into Available Light, Gehry’s striking set composed of a large platform on which one to three dancers perform at a time, while a larger ensemble dances below them on the stage proper. (During the company’s three-week residency at MASS MoCA, Gehry’s set, with its chain-link backdrop, looked as if it was tailor-made for the North Adams museum, which is housed in a cluster of former factories whose past industry is celebrated, rather than veiled.) This “split image,” as Childs refers to it, adds to that choreographic layering. Yet rather than confuse, the additional levels of movement thrill the eye. There’s much going on in one sense, but it’s also all been built up for us, one phrase at a time. By design, Childs helps us to learn the map of the dance, to get our bearings, though there are still subtle enigmas along the way. The outcomes of Available Light—the individual phrases as well as the whole of the piece—feel inevitable, but not predictable.

Since 1989, Janine Parker has been writing about dance for The Boston Phoenix and The Boston Globe. A former dancer, locally she performed with Ballet Theatre of Boston, North Atlantic Ballet, Nicola Hawkins Dance Company and Prometheus Dance. Ms. Parker has been teaching for more than 25 years, and has a long history with Boston Ballet School. She is on the Dance Department faculty of Williams College in Western Massachusetts, where she has lived since 2003.

Tagged: Available Light, Frank Gehry, Janine Parker, John Adams, Lucinda Childs