Fuse Book Review: “Bomb’s Author Interviews” — Hipper Than Thou

Bomb Magazine’s goal is not merely to comment on the arts, it is about making art.

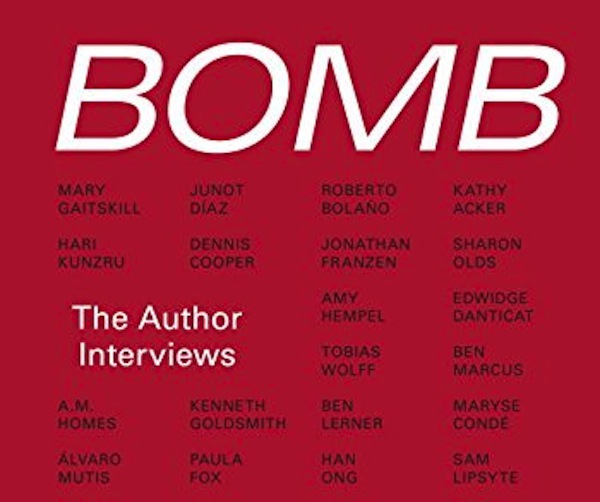

Bomb: The Author Interviews. Edited by Betsy Sussler. Soho Press, 480 pages, $28.97.

By Tim Barry

There’s always a danger when you suddenly meet people you’ve admired. Remember the buttery toast-crumb on Frances McDormand’s sweater when you encountered her in Bendel’s store? The weird disconnect of seeing Robert Reich in skin-tight biking shorts? And Robert Brustein, guiding spirit of the modern stage, would you like an Altoid?

Still, you relish the contact. Take Geoff Dyer, whose books Jeff In Venice and Paris Trance set a new standard for the comic novel. There’s value in discovering that, for instance, like myself, Dyer has “never made much progress with the novels of Robert Musil.” Or that Wayne Koestenbaum also had to “slog through Walter Benjamin.” When artists become humanized we see their work with fresh eyes. We realize that, like us, sometimes they’re just not that smart.

That was just one of the takeaways from reading Bomb Magazine’s handsome new anthology, The Author Interviews, edited by the hip literary journal’s co-founder, Betsy Sussler. Another was that I realized I’d never actually heard of Bomb Magazine. Which reminded me that I’m not that hip.

I have, however, heard of and have even occasionally understood the late critic Arthur C. Danto, who sums up Bomb this way: “it refers to the culture in its fluid and formative state, and in this way contributes to its direction.” So Bomb’s goal is not merely to comment on the arts, it is about making art. How hip is that?

Still, the interview as art form is not that radical a notion. The Paris Review’s many Writers On Writing anthologies top the field, a status that Bomb’s book does not threaten. Bomb’s format is different: the interviews are between two writers rather than Paris Review‘s approach of having the interview done by a little-known journalist. Bomb‘s jawboning-between-creators dynamic creates both opportunities and problems.

At their best, interviews careen in odd directions as the participants free-associate down compelling thought corridors. Like when Jonathan Safran Foer asks Jeffrey Eugenides, the author of Middlesex, “do you ever feel feminine?” Eugenides responded: “Do you know that Hemingway was made to dress like a girl until he was eleven or so? You could say he overcompensated later in life. When I was thirteen or fourteen I was very pretty. It seems amazing now, Jonathan, but that was the case. I’d be hanging out with a bunch of girls and one of their mothers would come out and say ‘Would you girls like something to drink?’ Bellow says in Humboldt’s Gift that being a poet is ‘a school thing, a skirt thing, a girl thing.’ So I’d say that being a writer you have to have something feminine about you.”

Interview subject Jeffrey Eugenides — there is something feminine about being a writer.

Or listen to Mary Gaitskill describe a mini-meltdown. “I was actually not a sophisticated person; I was lonely, socially ignorant, very shy….I’d be at these dinners with like, Sonny Mehta and some big agent. I had no idea what to say, and I felt that people expected me to be really sharp. They’d say things to me as if they were expecting me to hit the ball back really hard, and I would just freeze.”

Poor lamb. Reading that sent this writer’s memories reeling back to a similar moment, when he found himself at a party in Provincetown, drinking whiskey and trying on wigs with a group that included the writers Susan Choi, Darrach Dolan, Jhumpa Lahiri, and yes, Jeff Eugenides. When apropos of nothing Eugenides goes “Tim, you seem like a well-read guy….what can you tell me about Zoroaster?” All eyes turned expectantly, and yes, there it was, the long and awkward head-scratch….the split-second that seemed to last an hour…. the Gaitskill-freeze-moment.

If some bits of these interviews invite reflection, there are many more that transport us to worlds we’ve never known. Perch on Sapphire’s shoulder in a 125th Street Xerox shop, where she’s gone to copy some of the manuscript that became Precious.

And there was this brother in there with his gold chains and his jeans and he looked like he was getting ready to do a rap concert instead of Xeroxing, like he was supposed to be doing. I was mad, and I said to myself, ‘Now if this was a white girl he’d be Xeroxing faster, why is this guy taking so long to Xerox my shit?’ And then he turned around to me with tears in his eyes and he said, ‘Lady, did you write this here literature?’ I said, ‘Yes, I did.’ He said, ‘This is some bad stuff.’

To witness that encounter is gratifying, but even better are the glimpses we get into the creative process, how the ‘stuff’ becomes art. Ben Marcus recounts “the struggle and impossibility of bringing a book to life.” Junot Diaz tells Edwige Danticat about the importance of self-editing: “I write two score pages for every one I keep.” And Lydia Davis shares the strategy of parceling out her best ideas, not using them up all at once: “whatever impulse I have with one story there’s enough of that impulse left to do another story.”

This book is not a writing manual, but it does lay out the tools of the writer’s craft. Use them how you will. Sam Lipsyte and Christopher Sorrentino engage in a highly technical debate about “the various ways to approach prose composition,” bringing it around to the point that “if you’re writing seriously good work, it’s going to find a home. It’s just not going to provide you with a home.”

Indeed, the shrinking market for literature, and the iffy prospects for those trying to making a living by the pen is the elephant in the room here. How do writers survive today? Many of the group assembled here make a living teaching: Diaz at MIT and Donald Antrim at Columbia University. Jonathan Franzen apparently coasts along happily on the money generated by his best-selling novel The Corrections.

One of the book’s flaws pops up whenever these academic types lapse into chunks of arcane jargon. Sometimes intelligent people just like to hear themselves talk, though it slows the conversational flow considerably. Here, for example is Adam Fitzgerald: “….trying to rethink ontology through an existential awareness and demonstration of lexical instability (cue apophatic poetics.)” He does admit that he’s being pedantic here–ya’ think?

Tim Barry studied English literature at Framingham State College and art history at the University of Massachusetts-Dartmouth. He has written for Take-It Magazine, The New Musical Express, The Noise, and The Boston Globe. He owns Tim’s Used Books, Hyannis, and Provincetown, and TB Projects, a contemporary art space, in Provincetown.

That last paragraph eluded ignorant me. I’ve never been able to quite understand ontology (or tautology, for that matter), I have no familiarity with the word “apophatic,” and I’ve never heard of Adam Fitzgerald.

Engaging article. Seems like the book, though, kind of trivializes art.