Book Review: “The Water-Babies” — A Darwinian Fairy Tale by an Eccentric’s Eccentric

Why is The Water-Babies a classic English fairy tale? It doesn’t take itself too seriously, yet it doesn’t ignore important issues. It’s culturally irreverent without being juvenile or simplistic.

The Water Babies by Charles Kingsley. Oxford World Classics, 288 pages, $15.95

By Matt Hanson

Now available in an Oxford University World Classics edition of its original first-edition text, The Water-Babies, a Fairy Tale for a Land Baby is a bizarre (and beloved) children’s story that, like the best so-called children’s stories, isn’t written solely for kids. In fact, this speculative adventure, first published in the early 1860s, should be placed in the tradition of seriously whimsical tales whose surface-level inventiveness comes dangerously close to overshadowing their philosophical depth and social conscience. This fantastical meditation reads like a mixture of Lewis Carroll and Jonathan Swift with quite a few metafictional flourishes, a la Tristram Shandy, added for good measure.

Young Tom begins the story as a chimney-sweeper, a social casualty of industrial Victorian London who takes the abuse of his master and the general wretchedness of his lot for granted. Luckily, his attitude changes during an excursion to the country, where he wriggles away and accidentally finds himself in the immaculately clean room of an upper-class girl, where he catches a surprising glimpse of his own filthy complexion in the mirror. The next thing he knows, he’s being chased from the premises and finds a sparkling country river to wash his face clean and in which he accidentally drowns.

Of course, Young Tom isn’t dead, quite the contrary — his metamorphosis from land-baby to water-baby has just begun. As Tom sheds the grime of London he becomes the newest member of the delightfully strange world he finds underneath the waves. It’s a place populated by a unique bunch – cherubic fellow water babies, talkative crustaceans who explain their origin stories in intricate detail, and iridescent schools of fish that don’t, strictly speaking, fit any earthly biological classifications at all.

The Water-Babies was written in part for moral instruction, but it is a didactic text whose most obvious lessons aren’t the most interesting ones. Tom is gradually taught the golden rule as well as made aware of the illogical ways of the grownup world through homilies given by two old sisters tellingly named Mrs Doasyouwouldbedoneby and Mrs Bedonebyasyoudid. The river becomes a dreamlike alternative to reality, an oasis whose refreshing spirit rebukes the cruelty and exploitation of the world of adults back on land. Tom can’t believe what he’s seeing and hearing, at least at first. One of the subtler mottoes of the story is that it’s initially very hard to believe in water babies, even if you are one.

As the narrator puts it in one of his many self-conscious digressions, breaking the fourth wall to offer a rebuttal for any doubts about the narrative’s tenuous plausibility: “How do you know that? Had you been there to see? And if you had been there to see, and seen none, that would not prove that there were none…and no one has the right to say that no water babies exist till they have seen no water babies existing, which is quite a different thing, mind, from not seeing water babies.”

Author Charles Kingsley was well suited to defend the logic of fairy tales, especially yarns inspired by the changeability of the natural world. He was a 19th Century English version of a renaissance man: a novelist, professor, poet, historian, political activist, and devout clergyman who saw no philosophical dilemma in terms of balancing his faith with his equally enthusiastic embrace of evolutionary science. Kingsley was an admirer and correspondent of Charles Darwin’s and was one of the first to receive an advance copy of On the Origin of Species, writing an approving blurb that was subsequently added to later editions.

According to Robert Douglas-Fairhurst’s lively introduction, Kingsley was also an eccentric’s eccentric in a country (and a century) brimming with them. He is described as a veritable menagerie of contradictions, “a shy extrovert; a no-nonsense sentimentalist…a man of fads and crazes” who “directed his energies towards one object after another.” If there was no one around for conversation, Kingsley was the kind of person who would talk to himself out loud. Crucially, however, Kingsley was no quack. He held important positions at the heart of the Victorian establishment (at one point, he served as Queen Victoria’s personal chaplain) and was a popular author, with The Water-Babies as his most enduring creation.

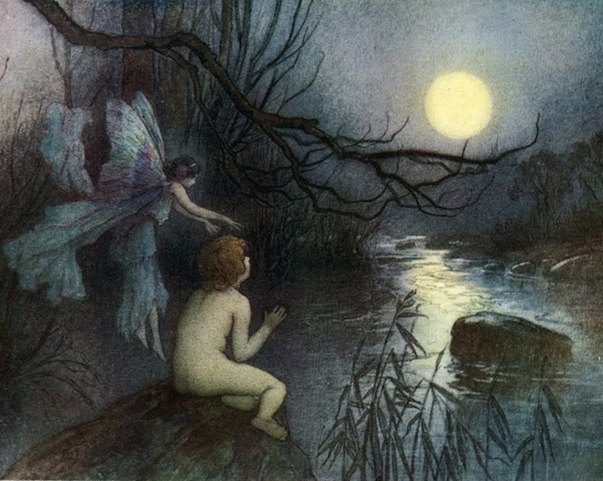

“He watched the moonlight on the rippling river.” Illustration for a 1909 edition of “The Water-Babies.”

It’s easy to see why The Water-Babies has been adapted for film and has been reissued in numerous illustrated editions. The story doesn’t take itself too seriously, but it is never afraid of engaging with important issues, including child labor and anti-scientism. (Paul Farley, who adapted the book for the BBC in 2013, sees it as a proto-conservationist tract.) It’s culturally irreverent without being juvenile or simplistic. The great 19th Century scientific debates over the Hippocampus as a possible evolutionary missing link, in which Kingsley participated, are playfully re-christened in the pages of The Water-Babies as the Hippopotamus Debate, and explained in thorough but good-humored detail, breaking down sophisticated scientific terms in a language fun to read and accessible to eager youngsters and curious adults alike.

With all the recent political indignation about the evils of scientific inquiry and how they endanger belief, Kingsley’s generous and positive (theistic) interpretation of Darwinism comes off as refreshingly enlightened, even modern. The fact that The Water-Babies is so imaginatively stimulated by Darwin’s work challenges the hostility many conservatives express towards what they see as the nihilism posed by evolution. Not only is the book a playful satire in support of Darwin’s vision, but it is also an engaging daydream about what the world looks like for those who need to go underground to swim a bit to find their way back to shore.

The vividness with which Kingsley imagines the world of the water babies he describes makes it as real as it can ever be, and spiritedly calls into question why people find it so necessary to strictly separate the fictional from the real, the child from the adult, and the land from the water. As the narrator reminds us, with an ironic chuckle, as the story winds down: “remember always… that this is all a fairy tale, and only fun and pretense; and, therefore, you are not to believe a word of it, even if it is true.”

Matt Hanson is a critic for the Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.